Pierre-Paul Grassé facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

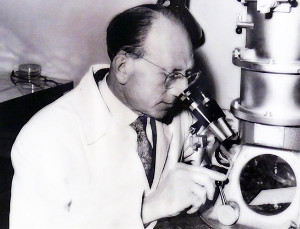

Pierre-Paul Grassé

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 27 November 1895 Périgueux, Dordogne, France

|

| Died | 9 July 1985 (aged 89) Carlux, Dordogne, France

|

| Education | University of Bordeaux |

| Known for | Support of Neo-Lamarckism |

| Awards | Prix Gadeau de Kerville of the Société entomologique de France, member of the Académie des sciences, commander of the Légion d'honneur, doctor honoris causa of several universities |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Entomologist |

| Institutions | École Nationale Supérieure Agronomique de Montpellier, University of Clermont-Ferrand, Université de Paris |

| Thesis | Contribution à l'étude des flagellés parasites |

| Influences | Octave Duboscq |

Pierre-Paul Grassé (born November 27, 1895, in Périgueux, France – died July 9, 1985) was a famous French zoologist. A zoologist is a scientist who studies animals. He wrote more than 300 scientific papers and a huge 52-volume book series called Traité de Zoologie.

Grassé was a top expert on termites, which are tiny insects that live in big colonies. He was also one of the last scientists to support a theory of evolution called Neo-Lamarckism.

Contents

About Pierre-Paul Grassé

Early Life and Education

Pierre-Paul Grassé started his studies in his hometown of Périgueux. His parents owned a small business there. He first studied medicine at the University of Bordeaux. At the same time, he also studied biology. He learned a lot from an insect expert named Jean de Feytaud.

His studies were stopped for four years because of World War I. He served as a military surgeon during the war. After the war, he went to Paris to focus only on science. He earned his degree in Biology.

In 1921, Grassé became a professor at the National Higher School of Agronomy in Montpellier. There, he met Octave Duboscq, who encouraged him to study tiny protozoan parasites. Later, he learned about experimental embryology, which is the study of how living things develop from an early stage.

In 1926, he became the vice-director of a school that taught about silkworm farming. He also finished his main research paper, called Contribution à l'étude des flagellés parasites, which was about tiny parasites.

Teaching and Research

In 1929, Grassé became a zoology professor at the University of Clermont-Ferrand. He helped many students with their research on insects. He traveled to Africa several times, starting in 1933, to study termites. He became one of the world's leading experts on these insects.

In 1935, he moved to the Université de Paris as an Assistant Professor. He won an award for his work on orthoptera (like grasshoppers) and termites. He also led important scientific groups, including the Société zoologique de France and the Société entomologique de France.

In 1944, he became the head of Zoology and the Evolution of Beings at the University of Paris. He was chosen to be a member of the French Academy of Sciences in 1948. This is a very high honor for a scientist in France. He even became the president of the Academy in 1967.

Grassé received many awards and honors throughout his career. He was made a commander of the Légion d'honneur, which is France's highest award. He also received honorary doctorates from many universities around the world. He helped start the French Society of Parasitology in 1962.

Major Publications

Starting in 1946, Pierre-Paul Grassé began a huge project called Traité de zoologie (Treatise of Zoology). This massive work had 38 volumes and took almost 40 years to complete. Many top zoologists helped him write it. Even today, these books are important guides for studying different animal groups. Ten volumes focused on mammals, and nine on insects.

He also wrote a three-volume work called Termitologia (1982-1984). This book, over 2400 pages long, collected all the known information about termites. He started studying termites by looking at the tiny living things that live inside them.

In Termitologia, Grassé introduced an idea called Stigmergy. He explained it like this: "Stigmergy happens in a termite mound when the work of one builder encourages and guides the work of its neighbor." This means that termites don't need a leader; their actions simply trigger others to act.

Grassé also started three science magazines: Arvernia biologica (1932), Insectes sociaux (1953), and Biologia gabonica (1964). Besides his scientific papers, he wrote books for the general public, like La Vie des animaux (The Life of Animals). He also wrote articles for the Encyclopædia Universalis on "Evolution" and "Stigmergy."

He also wrote several books about his ideas on evolution and philosophy, such as L’Évolution du vivant (The Evolution of the Living).

Views on Evolution

Neo-Lamarckism

Pierre-Paul Grassé was a strong supporter of Lamarckism, a theory of evolution. This theory, named after Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck, suggests that living things can pass on traits they gain during their lifetime to their offspring. For example, if an animal develops stronger muscles from exercise, Lamarckism suggests its babies might be born with stronger muscles.

Grassé held an important position at the University of Paris that focused on evolutionary biology. The scientists who held this position before him also supported Lamarckism.

In 1947, Grassé organized a big meeting in Paris about "paleontology and transformism" (another word for evolution). Many important French scientists attended. They were often against some ideas of neo-Darwinism, which is the more widely accepted theory of evolution today. Neo-Darwinism focuses on natural selection and gene changes. Grassé believed that Lamarck had been unfairly criticized and should be recognized more.

Evolution of Living Organisms

In his 1973 book, L'évolution du vivant (translated as Evolution of Living Organisms), Grassé shared his arguments against neo-Darwinism. He disagreed with the idea that living things evolve mainly by adapting to their environment.

He pointed to "living fossils" as an example. These are species that have not changed much over millions of years, even though their environment has changed a lot. He argued that evolution is not always "necessary" and doesn't happen just because of outside forces. Instead, he thought that evolution comes from something inside the living things themselves.

Other scientists reviewed Grassé's book. Biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky felt that Grassé's idea that evolution is guided by an unknown internal factor didn't really explain anything. He said that rejecting what is known and hoping for a future discovery isn't good science.

Colin Patterson, another scientist, also reviewed the book. He noted that Grassé believed paleontology (the study of fossils) was the "only true science of evolution," which Patterson disagreed with. Patterson also found Grassé's own theory of Neo-Lamarckism hard to understand.

Geologist David B. Kitts also reviewed the book negatively. He said that many of Grassé's arguments against Darwin's theory had been made before and were already answered by most Darwinian scientists. Kitts also pointed out that Grassé himself said that understanding the internal factor driving evolution might be more about philosophy than biology.

Selected Works

- 1935: Parasites et parasitisme (Parasites and Parasitism)

- 1935: with Max Aron, Précis de biologie animale (Summary of Animal Biology) – a textbook that went through many editions.

- 1963: with A. Tétry, Zoologie (Zoology) – two large volumes.

- 1973: L'évolution du vivant, matériaux pour une nouvelle théorie transformiste (The Evolution of the Living, Materials for a New Transformist Theory) – a book criticizing neo-Darwinism.

- 1982-1986: Termitologia – a three-volume work on termites.

See also

In Spanish: Pierre-Paul Grassé para niños

In Spanish: Pierre-Paul Grassé para niños

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |