Piracy in the Sulu and Celebes Seas facts for kids

The Sulu Sea and Celebes Seas are large areas of water in Southeast Asia. They cover about 1 million square kilometers. For a very long time, even before countries like the Philippines were formed, these seas have had problems with illegal activities. Today, these activities still pose a threat to the countries nearby.

While piracy (attacking ships to steal things) has always been a big problem here, recent incidents also include other crimes. These include kidnapping people, and illegally trading humans and weapons. Most of these attacks are called 'armed robbery against ships' because they happen in waters that belong to a country. In the Sulu and Celebes Seas, pirates often kidnap crew members from ships. Since March 2016, there have been many kidnappings, leading to warnings for ships traveling through the area.

Contents

History of Piracy in the Region

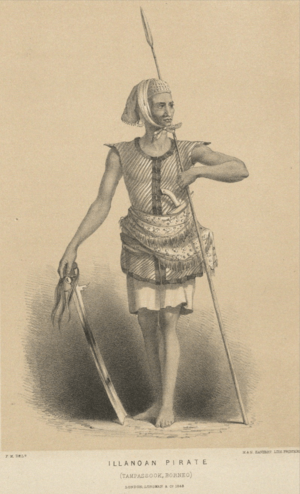

Piracy in the Sulu Sea and Celebes Seas has a very long history. Many attacks and raids came from the southern Philippines, especially from groups like the Ilanun (or Iranun) and the Sama sea nomads. The powerful Tausug leaders from Jolo Island were also involved. Historically, pirates often attacked the Spanish around the island of Mindanao. These fights are often called the Spanish-Moro conflict.

The Spanish called the local Muslims "Moro." This term was used negatively by the Spanish because these groups fought against Spanish rule and Christianity. However, today, many Filipinos are taking back the term "Moro" to show pride in their Muslim identity. So, we will use this term in this article.

Because of the many wars between Spain and the Moro people, piracy attacks happened often in the Sulu Sea. These attacks were not stopped until the early 1900s. It's important to remember that not all Moro groups were pirates. Some were naval forces or privateers (people allowed by a government to attack enemy ships). However, many pirates did operate with government permission during wartime.

Moro Pirates and Spanish Rule

Moro piracy is closely linked to when Spain ruled the Philippines. For over 250 years, Moro pirate raids caused a lot of suffering for Christian communities. After the Spanish arrived in 1521, Moro raids began in June 1578. These attacks spread across the islands. The pirates had organized fleets with weapons almost as good as the Spanish.

These attacks are often seen as a reaction against the Spanish. The Moros felt the Spanish had taken away their power and control over important trade spots in Mindanao. Religious differences between Muslims and Christians also played a big role.

The Spanish fought the Moro pirates often in the 1840s. For example, in 1848, a Spanish force attacked Balanguingui. They fought against over 1,000 Moros hidden in forts. The Spanish won, freeing over 500 prisoners.

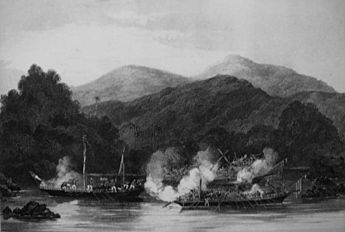

In the 1840s, James Brooke became the "White Rajah" of Sarawak. He also led campaigns against the Moro pirates. In 1843, he attacked pirates at Malludu. In 1847, he fought a big battle at Balanini, where many pirate ships were captured or sunk. Even in 1862, his nephew sank four pirate ships by ramming them with his steamship.

Despite Spanish efforts, piracy continued until the early 1900s. Spain gave the Philippines to the United States after the Spanish–American War in 1898. American troops then worked to bring peace from 1903 to 1913. This helped stop piracy in the southern Philippines.

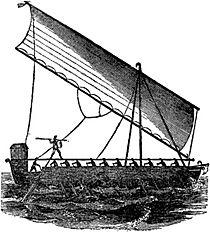

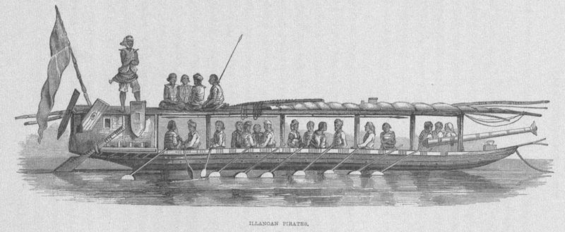

Pirate Ships

The Moro pirates used different kinds of ships, like the paraw, pangayaw, garay, and lanong. Most were wooden sailing galleys called lanong. They were about 27 meters long and 6 meters wide. They carried around 50 to 100 crew members.

Moro ships usually had three swivel guns, called lelahs or lantakas. Sometimes they had a heavy cannon. Their ships were very fast. Pirates would attack merchant ships that were stuck in shallow water in the Sulu Sea. Slave trading and raiding coastal towns were also common. Pirates would gather large fleets of ships and attack villages. Over centuries, hundreds of Christians were captured and imprisoned. Many were forced to work as galley slaves on pirate ships.

Weapons

Besides muskets and rifles, Moro pirates used a sword called the kris. It had a wavy blade that made wounds hard to heal. The handle was often decorated with silver or gold. The kris was often used when boarding another ship. Moros also used the Kampilan sword, a knife called a barong, and a spear made of bamboo with an iron head.

The Moro's swivel guns were older and less accurate than modern guns. Lantakas dated back to the 16th century and could be up to 1.8 meters long. They needed several men to lift them and fired small cannonballs or grape shot.

Piracy After World War II

Piracy came back after World War II. This was because security was weak, and many military engines and modern guns were available. Police in the newly independent Philippines struggled to control the illegal trade of weapons and goods.

New pirate groups mostly came from the southern Philippines, from Muslim ethnic groups. In northern Borneo, the Tawi-Tawi pirates were a concern for British rule. They were thought to be descendants of 19th-century pirates. Between 1959 and 1962, authorities in North Borneo recorded 232 pirate attacks.

During this time, pirates mainly targeted traders, but also attacked fishing and passenger boats. They raided coastal villages too. For example, in 1985, pirates attacked Lahad Datu in Sabah, killing 21 people. The spread of weapons from armed rebellions made the pirates even more violent. Philippine authorities reported over 431 deaths and 426 missing people in 12 years, making the region very dangerous. Victims were often forced to jump into the water, which explains the high number of missing people.

Armed groups like the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), founded in 1972, and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), founded in 1977, also started using piracy. They used it to fund their fight. The MNLF sometimes demanded protection money from fishermen. Similarly, Abu Sayyaf, started in the early 1990s, also began piracy for money.

Modern Piracy

2000–2014

Around the year 2000, piracy remained a big threat. Small boats were often attacked, and towns and businesses on coastal villages in Sabah were raided. These attacks were mostly done by groups from the southern Philippines.

The 2000 Sipadan kidnappings got a lot of international attention. This made the Malaysian government increase its efforts against piracy. They added more law enforcement and built naval bases in places like Semporna and Sandakan. These efforts, along with agreements like RECAAP, helped reduce incidents. For a while, piracy in Southeast Asia was less common than piracy in Somalia.

However, from 2009 to 2014, the number of attacks in Southeast Asia went up again. This was mainly due to incidents in the Strait of Malacca and South China Sea. But raids on towns and businesses also returned as a threat in the Sulu and Celebes area after 2010. In 2014, the Philippine government signed a peace deal with the MILF. But violence continued due to other groups like Abu Sayyaf or unhappy MILF members.

Piracy attacks in the Sulu Sea are usually carried out by small, well-armed groups of fewer than ten people. These incidents tend to be more violent than attacks in other parts of the world. Pirates use handguns and rifles like AK47s and M16s. They almost always target small boats, including fishing boats, passenger ships, and transport vessels.

While pirates mainly want to steal personal items, cargo, and fish, they also take hostages for ransom. In recent years, there has been a rise in these types of incidents. Sometimes, pirates also steal the boat's outboard motors or the entire vessel to sell or keep.

Countries in the region respond in three ways: by doing maritime operations, sharing information, and building up their abilities. Even though countries were slow to work together in the past, the growing problem forced them to act. Information sharing improved with the RECAAP agreement in 2006. Even countries not officially part of it, like Malaysia and Indonesia, still share information.

2014–2021

Southeast Asia saw a big drop in piracy from 2014 to 2018. The number of incidents went from 200 a year down to 99 in 2017. However, this was mostly due to efforts in the Straits of Malacca and did not apply to the Sulu and Celebes region.

Since 2016, the type of piracy in this area changed. The extremist group Abu Sayyaf became active again, focusing on kidnapping people for ransom. The years 2016 and 2017 were the worst, with 22 incidents and 58 crew members kidnapped in the first year alone.

At first, mostly fishing trawlers and tug boats were targeted. After October 2016, larger ships also became targets. By June 2019, 29 incidents of crew abduction were reported, with 10 people dying. In 2020, only one incident was reported. Even though attacks have decreased, warnings are still in place for ships to avoid the Sulu and Celebes Seas.

Nature of Piracy

Today, attacks in the Sulu and Celebes Seas are mainly about kidnapping for ransom. This is different from other parts of Southeast Asia, where attacks are usually non-violent robberies.

All attacks have happened while ships were moving. Tug and fishing boats are the main victims because they are slow and have low sides, making them easy to board. Since many attacks are linked to Abu Sayyaf, the ransom money likely helps fund this extremist group. The cruelty used in abducting and holding hostages has drawn international attention.

Country Responses

The countries nearby – Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines – are now focusing on working together more. Because of the kidnapping attacks in their waters, they signed a Trilateral Cooperative Agreement (TCA) in July 2016. This agreement helps them coordinate maritime security. It includes sharing information, doing joint border patrols, and setting up standard procedures for maritime patrols.

The three countries also set up Maritime Command Centres in places like Tarakan and Tawau. These centers help manage operations and monitor the seas. Also, like efforts to fight piracy in Somalia, Malaysia and the Philippines created special transit corridors. These are safe paths for commercial ships. Ships need to tell one of the Command Centres 24 hours in advance so they can get help if needed. In 2018, the three countries also formed a Contact Group on Maritime Crime in the Sulu and Celebes Seas.

Why Piracy Continues

Even with efforts by Malaysian and Philippine authorities, piracy in the Sulu Sea continues. Some reasons include weak law enforcement at sea, corruption, and disagreements between the countries involved. Sometimes, security forces are even involved in helping pirates by giving them weapons or information.

The geography of the Sulu Sea makes it easy for pirates to surprise victims and escape. On land, poor economic conditions push people to crime, including piracy, to make a living. In turn, piracy makes life even harder for local people, as they are often the main targets.

The continued existence of groups like Abu Sayyaf and MILF also contributes to piracy. These groups not only engage in piracy themselves, but fighting them also uses up resources that could be used to stop piracy. Sometimes, efforts by security forces can even push local people towards piracy if their livelihoods are harmed. There are also many small weapons in the area because of weak government control and armed conflicts, making it easy for pirates to get guns.

Cultural factors might also play a part. Many modern pirates in the Sulu Sea are descendants of historical pirates. This can make piracy seem less like a crime in their culture. Some believe piracy might be linked to ideas of honor and masculinity. Also, piracy is not always seen as a crime by people living near the Sulu Sea, which is reflected in their local languages.

Piracy Statistics

Information on piracy incidents in the region often comes from reports by the Piracy Reporting Centre of the International Maritime Bureau (IMB) or the Information Sharing Centre of ReCAAP. Data from the International Maritime Organization is not used much because they only report from two locations: the Straits of Malacca and the South China Sea.

The numbers can differ depending on how each organization collects and classifies information. For example, the IMB gets data from shipowners, while ReCAAP gets it from official staff and coast guard officers. Also, some incidents might not be reported, or some might be reported without full details. Shipmasters might not report attacks because they fear delays or higher insurance costs. Attacks on local fishing boats are often not reported due to a lack of infrastructure or trust in authorities. So, understanding piracy statistics requires looking closely at how the data was gathered.

Gallery

-

An engagement with pirates off Sarawak in 1843

-

The Spanish landing at Balanguingui by Antonio Brugada

-

Kris from Java

-

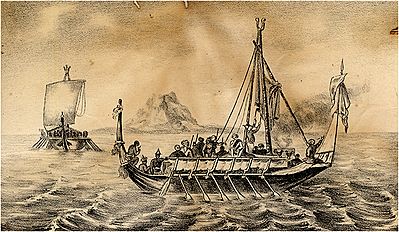

Garay warships in the Sulu Sea, c. 1850

See also

In Spanish: Piratas moros para niños

In Spanish: Piratas moros para niños

- Piracy

- Piracy in the 21st century

- Slavery in the Sulu Sea

- Timawa

- Marina Sutil

- Barbary Pirates

- Caribbean Pirates

- Spanish–Moro conflict

- Philippine–American War

- Cross border attacks in Sabah

- Thalassocracy

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |