Pithole, Pennsylvania facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Pithole

Pit Hole

|

|

|---|---|

The site of Pithole in October 2009. The visitor center is visible at the top of the hill.

|

|

| Etymology: Pithole Creek | |

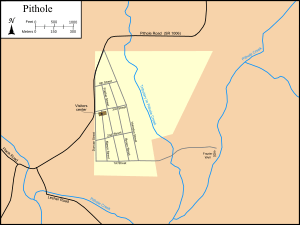

Map of Pithole and the surrounding area showing the city streets and Frazier Well, overlaid with modern roads and creeks

|

|

| Country | United States |

| State | Pennsylvania |

| County | Venango |

| Founded | May 24, 1865 |

| Incorporated | November 30, 1865 |

| Unincorporated | August 1877 |

| Elevation | 1,316 ft (401 m) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| NRHP # | 73001667 |

Pithole, also known as Pithole City, is a famous ghost town in Pennsylvania, United States. It is about 6 miles (9.7 km) from Oil Creek State Park. This park is home to the Drake Well Museum, where the first commercial oil well in the United States was drilled.

Pithole became well-known because it grew incredibly fast and then disappeared just as quickly. It was a "proving ground" for the new petroleum industry, meaning it was a place where new ideas and methods for getting oil were tested.

In January 1865, oil was discovered nearby. This brought many people, especially land buyers, to the area that would become Pithole. The town was planned in May 1865. By December of that year, it was officially a town with about 20,000 people.

At its busiest, Pithole had over 54 hotels, 3 churches, and the third-largest post office in Pennsylvania. It also had its own newspaper, a theater, a railroad, and the world's first oil pipeline. However, by 1866, Pithole's growth and oil production slowed down. New oil discoveries in other towns and several big fires caused people to leave. By 1877, the town was no longer officially recognized.

In 1961, the land was cleared and given to the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. A visitor center was built in 1972, showing exhibits about Pithole's history. Pithole was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.

Contents

What's in a Name? The Story of Pithole

The city of Pithole got its name from Pithole Creek, a stream that flows through Venango County into the Allegheny River. But where the name "Pithole" itself came from is a bit of a mystery!

One idea is that early explorers found strange cracks in the ground. These cracks let out sulfurous fumes. Such "pit-holes" are found where Pithole Creek meets the Allegheny River. Some were 14 inches (36 cm) wide and 8 feet (2.4 m) long.

Another idea suggests the name came from ancient pits dug by early settlers. These pits were about 8 feet (2.4 m) wide and 12 feet (3.7 m) deep. They were lined with wood soaked in oil. These "pit-holes" were found near Oil Creek and in Cornplanter Township. They might even be older than the Seneca people who lived there later.

Oil Underground: Pithole's Geology

Most of the oil found in northwestern Pennsylvania came from sandstone layers deep underground. These layers are called reservoir rocks. Over time, the oil moved upwards and got trapped under a strong layer of rock called caprock. This created oil reservoirs.

The depth of these oil reservoirs varied a lot. Some were as deep as 4,000 feet (1,200 m), while others were almost at the surface.

Many oil wells near Pithole tapped into a sandstone layer known as the Venango Third sand. This layer held a lot of oil under high pressure. It was found only 450 to 550 feet (140 to 170 m) below the ground. Other oil layers, like the Venango First and Second sands, were also found.

Where Pithole Was: Geography and Climate

Pithole is located in northwestern Pennsylvania. It is about 50 miles (80 km) southeast of Erie. The closest towns are Titusville, about 8 miles (13 km) northwest, and Oil City, 9 miles (14 km) southwest.

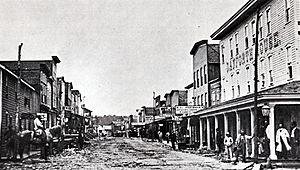

Pithole was designed with four main streets running east-west: First, Second, Third, and Fourth. Five other streets ran north-south: Duncan, Mason, Prather, Brown, and Holmden. All streets were 60 feet (18 m) wide, except for Duncan Street, which was 80 feet (24 m) wide.

Summers in Pithole were warm, with average high temperatures around 81 °F (27 °C) in July. Winters were cold, with average low temperatures around 13 °F (−11 °C) in January. The area received about 44 inches (1,100 mm) of rain each year. This heavy rain made Pithole's unpaved streets very muddy. Parts of First and Holmden Streets had to be covered with planks or logs to stop wagons and animals from getting stuck in the mud.

Pithole's Story: From Boom to Bust

The area around Pithole was once home to the Erie people. They were later replaced by the Iroquois in 1653. In 1784, the Iroquois gave the land to Pennsylvania. Venango County was formed in 1800.

In 1859, Edwin Drake successfully drilled the first oil well near Titusville. Soon, over 500 wells were built along Oil Creek. However, Pithole Creek did not get much attention at first. People preferred to drill on flatter land near larger rivers.

In January 1864, Isaiah Frazier leased land along Pithole Creek. He and his partners formed the United States Petroleum Company. They started drilling what was called the United States Well, or Frazier Well, in June. On January 7, 1865, the Frazier Well struck oil!

The Oil Boom: Pithole's Fast Growth

Just two weeks after the Frazier oil strike, the Twin Wells nearby also found oil. In May 1865, A. P. Duncan and George C. Prather bought the Holmden Farm, where the wells were located. They paid a lot of money for it. The wooded area overlooking the wells was cleared, and the town of Pithole was planned.

Lots of land were put up for sale on May 24. By July, the population was already about 2,000 people. By September, it reached 15,000, and by Christmas, it was 20,000! Pithole officially became a town on November 30, 1865.

Since many people were only staying for a short time, Pithole had 54 hotels. These ranged from simple rooming houses to fancy places like the Chase and Danforth Houses. The Astor House, Pithole's first hotel, was built in just one day! The Pithole Post Office, located in the Chase House, became the third busiest in Pennsylvania, after Philadelphia and Pittsburgh.

Three different churches were built: Catholic, Methodist, and Presbyterian. Pithole also had its own newspaper, the Pithole Daily Record, which started on September 5, 1865. The largest building was Murphy's Theater, which had three stories and could seat 1,100 people. It opened on September 17.

As more oil was produced, transporting it became a big problem. Teamsters, who used horses and wagons, were the main way to move oil. They were known for treating their horses badly, and the horses often lost their hair from oil and only lived a few months. This caused a shortage of horses. Teamsters also charged very high prices, especially when roads were bad.

To solve the transportation problem, some investors built a plank road (a road made of wooden planks) from Pithole to Titusville. Samuel Van Sykle, an oil buyer, invented the world's first oil pipeline. It opened on October 9, 1865. This 2-inch (51 mm) wide, 5.5-mile (8.9 km) long pipeline connected Pithole to the Oil Creek Railroad. It could move 81 barrels of oil per hour, which was like 300 teams of horses working for 10 hours!

The Oil City and Pithole Branch Railroad (OC&P) opened on December 18. It ran from Oleopolis and had stops at Bennett, Woods Mill, and Prather. Another new idea developed in Pithole was the railroad tank car. These were basically two wooden tanks, each holding 80 barrels of oil, placed on a flat train car.

The Bust: Pithole's Decline

In March 1866, a group of banks owned by Charles Vernon Culver, a politician, failed. This caused a money panic in the oil region. People stopped investing in Pithole, and the town began to slow down.

On February 24, a house caught fire, and strong winds spread the flames. In just two hours, most of Holmden Street and parts of other streets were destroyed. Another big fire on August 2 burned down several city blocks and 27 oil wells.

As new oil strikes happened in other parts of Venango County in 1867, people started to leave Pithole. Many even took their houses and businesses with them! By December 1866, the population had dropped to only 2,000. The local newspaper moved to Petroleum Center in July 1868. Even the Chase House hotel and Murphy's Theater were sold and moved to Pleasantville.

The 1870 census showed Pithole's population was only 237 people. The town's official status was removed in August 1877. The remaining land was sold in 1879 for just $4.37. The Catholic church was taken apart and moved to Tionesta in 1886. The Methodist church was kept usable for a while but was taken down in the 1930s. A stone altar was built and dedicated by the Methodist Episcopal Church on August 27, 1959.

Visiting Pithole Today

In 1957, James B. Stevenson, a newspaper publisher, bought the Pithole site. He cleared away the overgrown bushes and donated the land to the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission in 1961. Today, you can still see a few foundations and mowed paths that show where the buildings and streets once were.

The Pithole site was added to the National Register of Historic Places on March 20, 1973. You can take a walking tour of Pithole's 84.3 acres (34.1 ha) of old streets in about 42 minutes.

The visitor center was built in 1972. It is run by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission as part of the nearby Drake Well Museum. The visitor center has several exhibits, including a detailed scale model of Pithole when it was a busy city. There's also a display of an oil-transport wagon stuck in mud, and a small theater with information about the town. The visitor center is usually open from the end of May (Memorial Day weekend) through September (Labor Day). The season starts with the annual Wildcatter Day, which has music, tours, and other fun activities.

See also

In Spanish: Pithole para niños

In Spanish: Pithole para niños

- List of ghost towns in Pennsylvania

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Venango County, Pennsylvania

- Oil Region

- Pennsylvanian oil rush

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |