Financial crisis facts for kids

A financial crisis happens when many financial assets suddenly lose a lot of their value. Think of it like a sudden drop in the price of something valuable. In the past, many financial crises were linked to bank panics, where lots of people rushed to take their money out of banks. These panics often led to recessions, which are times when the economy slows down.

Other types of financial crises include stock market crashes, when stock prices fall sharply, or when bubbles burst. A bubble is when prices for something, like houses or company shares, get too high and then suddenly crash. There are also currency crises, where a country's money quickly loses its value, and sovereign defaults, when a government can't pay its debts.

Financial crises can make people feel like they've lost a lot of money. However, they don't always cause big changes in the real economy. For example, the famous tulip mania bubble in the 1600s caused a crisis for some, but didn't deeply harm the whole economy.

Many experts have ideas about why financial crises happen and how to stop them. But there's no single answer, and these crises still happen from time to time.

Contents

Types of Financial Crises

What is a Banking Crisis?

A bank run happens when many people suddenly try to take all their money out of a bank. Banks lend out most of the money they get from deposits. This is called fractional-reserve banking. So, it's hard for them to pay everyone back quickly if everyone asks for their money at once. A bank run can make a bank unable to pay its debts, meaning customers might lose their savings if they're not insured.

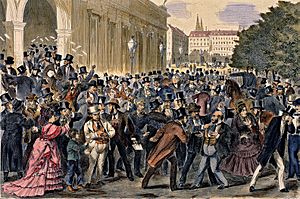

When bank runs happen in many banks at the same time, it's called a systemic banking crisis or banking panic. Famous examples include the run on the Bank of the United States in 1931 and the run on Northern Rock in 2007. Banking crises often happen after banks have lent money in risky ways, and many people can't pay back their loans.

What is a Currency Crisis?

A currency crisis means a country's money, or currency, suddenly loses a lot of its value. This is also called a devaluation crisis. For example, if a currency drops by at least 25% compared to other currencies, it's often considered a crisis.

It happens when people in the money market start to believe that a country's fixed exchange rate (where its money is tied to another currency) is about to fail. This belief causes people to sell that currency quickly. This selling makes the currency's value drop even faster, forcing the government to officially lower its value.

Speculative Bubbles and Crashes

A speculative bubble forms when the price of certain assets, like stocks or houses, becomes much higher than their true value. This often happens because buyers purchase an asset just to sell it later for a higher price. They don't care about the actual value or income the asset might create.

If a bubble exists, there's a big risk of a crash. This is when asset prices fall sharply. People keep buying only as long as they expect others to buy. But when many decide to sell, the price drops quickly. It's hard to know if an asset's price is its real value, so spotting bubbles can be tough. Some economists even say bubbles almost never happen.

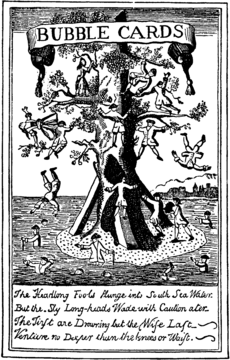

Well-known examples of bubbles and crashes include the Dutch tulip mania in the 1600s. Another was the South Sea Bubble in the 1700s. The Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the Japanese asset price bubble in the 1980s are also famous. More recently, the crash of the United States housing bubble from 2006-2008 caused big problems.

International Financial Crises

An international financial crisis can happen when a country with a fixed exchange rate is forced to lower its currency's value. This happens because it has too many debts compared to its income. This is called a currency crisis or balance of payments crisis.

When a country can't pay back its sovereign debt (money it borrowed), it's called a sovereign default. Governments might choose to devalue their currency or default on debt. But often, it's because investors suddenly stop trusting the country. This leads to a quick stop in money coming in or a sudden rush of money leaving the country.

For example, several European countries faced currency crises in 1992–93. They had to devalue their money or leave the European Exchange Rate Mechanism. The Asian financial crisis in 1997–98 also saw many currency problems. Many Latin American countries couldn't pay their debts in the early 1980s. The 1998 Russian financial crisis led to Russia's money losing value and the government not paying its bonds.

Wider Economic Crises

When a country's economy shrinks for two or more quarters (six months), it's called a recession. If a recession lasts a very long time or is very bad, it might be called a depression. A long period of slow growth, even if not negative, is sometimes called economic stagnation.

Some economists believe that many recessions are caused by financial crises. A big example is the Great Depression. Before it, many countries had bank runs and stock market crashes. The subprime mortgage crisis and bursting housing bubbles in 2008 also led to recessions in the U.S. and other countries.

However, some experts argue that recessions cause financial crises, not the other way around. They say that even if a financial crisis starts a recession, other things can make the recession last longer. For instance, economists Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz believed that the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and bank panics wouldn't have caused a long depression if the Federal Reserve hadn't made mistakes with money policy.

Why Financial Crises Happen

Everyone Doing the Same Thing

In financial markets, investors often try to guess what other investors will do. This is like a game where everyone tries to pick what they think others will find most beautiful. If someone thinks many investors will buy Japanese yen, they might expect the yen's value to go up. So, they also have a reason to buy yen.

Similarly, if a bank customer thinks other customers will take their money out, they might expect the bank to fail. This gives them a reason to take their own money out too. When people have a reason to copy what others do, it's called strategic complementarity.

If people strongly want to do what they expect others to do, it can lead to self-fulfilling prophecies. For example, if investors expect the yen's value to rise, this expectation can actually make it rise. If depositors expect a bank to fail, this can cause it to fail. So, financial crises are sometimes seen as a bad cycle. Investors avoid an asset or institution because they expect others to do the same.

Leverage: Borrowing to Invest

Leverage means borrowing money to make investments. This is often seen as a big reason for financial crises. If a company or person only invests their own money, the worst they can do is lose their own money. But if they borrow to invest more, they can potentially earn more. However, they can also lose more than they have.

Leverage makes the possible gains from investing much bigger. But it also creates a risk of bankruptcy, where a company can't pay its debts. When one company can't pay, it can spread financial problems to other companies. This is called contagion.

The amount of borrowing in the economy often goes up before a financial crisis. For example, borrowing to buy stocks (called "margin buying") became very common before the Wall Street Crash of 1929.

Asset-Liability Mismatch

Another factor in financial crises is asset-liability mismatch. This happens when the risks of an institution's debts and assets don't match up well. For example, banks let people take money out of their accounts at any time. But they use that money to give out long-term loans to businesses and homeowners.

This mismatch between short-term debts (deposits) and long-term assets (loans) is a reason why bank runs happen. If depositors panic and want their money back faster than the bank can get it from its loans, the bank is in trouble. Similarly, Bear Stearns failed in 2007–08. It couldn't get new short-term loans to pay for its long-term investments in housing-related securities.

In other countries, many governments can't sell bonds (promises to pay back money) in their own currency. So, they sell bonds in US dollars instead. This creates a mismatch between their debts (in dollars) and their income (local taxes). This means they risk not being able to pay their debts if exchange rates change.

Uncertainty and Herd Behavior

Many studies of financial crises point to mistakes made by investors. These mistakes can come from not knowing enough or from human thinking errors. Behavioural finance looks at these errors in economic thinking.

Historians like Charles P. Kindleberger noted that crises often follow big new financial or technical inventions. He called these "displacements" of investor expectations. Early examples include the South Sea Bubble in 1720. This happened when investing in company stock was new and strange. The Crash of 1929 followed new electrical and transport technologies. More recently, many crises followed changes in investing rules. The dot com bubble crash in 2001 arguably started with too much excitement about the Internet.

Not knowing much about new technologies can explain why investors sometimes guess asset values are much too high. Also, if the first investors in a new type of asset (like "dot com" companies) make money, others might follow. This drives prices even higher as people rush to buy, hoping for similar profits. If this "herd behaviour" pushes prices far above the true value, a crash might be unavoidable. If prices drop even a little, and investors realize gains aren't guaranteed, the spiral can reverse. Price drops cause a rush of sales, making prices fall even more.

Regulatory Failures

Governments try to stop or lessen financial crises by making rules for the financial world. One main goal of these rules is transparency. This means making a company's financial situation public. They do this by requiring regular reports using standard accounting rules. Another goal is to make sure companies have enough money to meet their promises. This is done through rules about how much money banks must keep and limits on how much they can borrow.

Some financial crises have been blamed on not enough rules. These crises have led to new rules to prevent them from happening again. For example, the former head of the International Monetary Fund, Dominique Strauss-Kahn, blamed the financial crisis of 2007–2008 on "regulatory failure to guard against excessive risk-taking". The New York Times also pointed to the lack of rules for certain financial products as a cause of the crisis.

However, too many rules have also been suggested as a cause of crises. Some rules have been criticized for making banks increase their money when risks go up. This might cause them to lend less money exactly when money is needed most, possibly making a crisis worse.

Fraud has also played a part in some financial company failures. Companies have tricked people with false claims about investments or stolen money. Examples include Charles Ponzi's scam in the early 1900s and the collapse of Madoff Investment Securities in 2008.

Many "rogue traders" who caused big losses at financial companies have been accused of fraud. They hid their trades. Fraud in housing loans was also a possible cause of the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis. Government officials said the FBI was looking into possible fraud by major housing finance companies.

Contagion: How Crises Spread

Contagion means that financial crises can spread. This can happen from one company to another, like a bank run spreading to many banks. Or it can spread from one country to another. This is seen when currency crises, government debt defaults, or stock market crashes spread across countries. When one financial company's failure threatens many others, it's called systemic risk.

A well-known example of contagion was how the Thai crisis in 1997 spread to other countries like South Korea. However, experts often debate if crises happening in many countries at once are truly due to contagion. They wonder if it's instead caused by similar problems that would have affected each country anyway.

Interest Rate Differences and Money Flows

In the 1800s, some theories suggested crises were caused by money flowing between areas with different interest rates. Money could be borrowed where rates were low and invested where rates were high. This allowed small profits with little capital.

But when interest rates changed, or the reason for the flow disappeared, money flows could suddenly reverse. The places that received investments might suddenly run out of cash, possibly becoming unable to pay debts. This could create a credit crunch. The banks that lent the money would be left with investors who couldn't pay them back, leading to a banking crisis.

Important Theories About Crises

Minsky's Theory of Financial Fragility

Economist Hyman Minsky suggested that financial weakness is a normal part of any capitalist economy. High weakness means a higher risk of a financial crisis. Minsky described three ways companies can finance themselves, based on how much risk they are willing to take:

- Hedge finance: Companies expect their income to cover all their payments, including loan interest and the original loan amount. This is the safest.

- Speculative finance: Companies expect income to only cover interest costs. They have to borrow more to pay back the original loan amount later.

- Ponzi finance: Companies don't even expect income to cover interest costs. They must borrow more or sell assets just to pay their debts. They hope asset values or income will rise enough later to pay everything off. This is the riskiest.

Financial weakness changes with the economy. After a recession, companies are careful and choose only safe (hedge) financing. As the economy grows and expected profits rise, companies start to take on more speculative financing. They believe profits will rise enough to pay back loans without much trouble. More loans lead to more investment, and the economy grows more.

Then, lenders also start to believe they will get their money back. So, they lend money to companies without full guarantees. Lenders know these companies might have trouble paying. But they believe these companies will just borrow from somewhere else as their expected profits rise. This is Ponzi financing.

At this point, the economy has a lot of risky debt. It's only a matter of time before a big company can't pay its debts. Lenders then understand the real risks and stop lending so easily. Many companies can't get new loans, and more companies fail. If no new money comes into the economy, a real economic crisis begins. During the recession, companies become careful again, and the cycle repeats.

Banking School Theory of Crises

This theory describes a continuous cycle driven by changing interest rates. It starts when short-term interest rates are low. Investors look for better returns in countries with higher rates, sending money there. Inside a country, short-term rates rise above long-term rates. This causes problems for those who borrowed short-term to invest long-term, especially if they can't quickly sell their investments.

Internationally, efforts to balance rates and stop money from leaving a country cause interest rates in the low-rate country to rise. The money flows then reverse or stop suddenly. The places that received investments are left without funds, and investors are stuck with assets that have lost value. Bankruptcies and bank failures follow as rates are pushed high. After the crisis, governments lower short-term interest rates again. This makes it cheaper to pay back government borrowing used to fix the crisis. Money then builds up again, looking for new investments, and the cycle starts over.

How the Global Financial Crisis Happened

The Global Financial Crisis (2007–2008) is the most recent and damaging financial crisis. It deserves special attention because its causes, effects, and how it was handled are very important for understanding today's financial system.

History of Financial Crises

A well-known book on financial crises is This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. It was written by economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff. They are considered leading historians of financial crises. They trace the history of crises back to sovereign defaults. These were when governments couldn't pay their public debts. This was the main type of crisis before the 1700s. Since then, crises involve both public and private debt problems. Reinhart and Rogoff also see lowering a currency's value and hyperinflation (very fast price increases) as types of financial crises. This is because they reduce the real value of debt.

Before the 1800s

Reinhart and Rogoff trace using inflation to reduce debt back to Dionysius I in ancient Syracuse. They start their "eight centuries" in 1258. Roman and Byzantine empires also lowered the value of their money. A financial crisis in 33 A.D. was recorded by Roman historians. It was caused by a lack of money.

Among the earliest crises they studied is England's default in 1340. This was due to problems in its war with France (the Hundred Years' War). Other early government debt defaults include seven by the Spanish Empire. Four happened under Philip II of Spain.

Other famous financial events since the 1600s include:

- 1637: The bursting of tulip mania in the Netherlands. While famous, its overall economic impact was small.

- 1720: The bursting of the South Sea Bubble (Great Britain) and Mississippi Bubble (France). These are considered the first modern financial crises. In both cases, companies took on the country's national debt, and then the bubble burst.

- 1763: The Amsterdam banking crisis of 1763 started in Amsterdam and spread.

- 1772: The Crisis of 1772 in London and Amsterdam. Twenty important London banks went bankrupt.

- 1783–1788: France's Financial and Debt Crisis. This was due to huge debts from wars.

- 1792: The Panic of 1792 in the US. It was caused by new credit from the Bank of the United States.

- 1796–1797: The Panic of 1796–1797. This British and US credit crisis was caused by a land speculation bubble.

The 1800s

- 1813: The Danish state bankruptcy of 1813.

- 1818: Financial Crisis of 1818 in England. Banks called in loans, taking money out of the U.S.

- 1819: The Panic of 1819. A widespread US economic slowdown with bank failures.

- 1825: The Panic of 1825. Many British banks failed, and the Bank of England almost did too.

- 1837: The Panic of 1837. A widespread US economic slowdown with bank failures. A five-year depression followed.

- 1847: The Panic of 1847. A British financial market collapse linked to the end of the 1840s railway boom.

- 1857: The Panic of 1857. A widespread US economic slowdown with bank failures. This was the first worldwide economic crisis.

- 1866: The Panic of 1866, mainly in Britain.

- 1869: Black Friday (1869), also known as the Gold Panic.

- 1873: The Panic of 1873. A widespread US economic slowdown with bank failures. It was called the "Great Depression" then.

- 1884: The Panic of 1884. A panic in the United States focused on New York banks.

- 1890: The Panic of 1890, also called the Baring Crisis. A major London bank almost failed.

- 1893: The Panic of 1893. A US panic caused by too much railroad building and shaky financing. This led to bank failures.

- 1893: The Australian banking crisis of 1893.

- 1896: The Panic of 1896. A severe economic slowdown in the US.

The 1900s

- 1901: The Panic of 1901. Limited to a crash on the New York Stock Exchange.

- 1907: The Panic of 1907. A widespread US economic slowdown with bank failures.

- 1910–1911: The Panic of 1910–1911.

- 1910: The Shanghai rubber stock market crisis.

- 1914: The Great Financial Crisis.

- 1929: The Wall Street Crash of 1929, followed by the Great Depression. This was the biggest economic depression of the 20th century.

- 1937–1938: A slowdown during the Great Depression in the United States.

- 1973: The 1973 oil crisis. Oil prices soared, causing a stock market crash.

- 1973–1975: The Secondary banking crisis of 1973–1975 in the United Kingdom.

- 1980s: The Latin American debt crisis, starting in Mexico in 1982.

- 1980s-1990: The Savings and loan crisis in the US.

- 1983: The Bank stock crisis (Israel 1983).

- 1987: Black Monday (1987). The largest one-day stock market percentage drop in history.

- 1988–1992: The 1988–92 Norwegian banking crisis.

- 1990: The Japanese asset price bubble collapsed.

- Early 1990s: Scandinavian banking crises, including in Sweden and Finland.

- 1991: The 1991 Indian economic crisis.

- 1992–1993: Black Wednesday. Attacks on currencies in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism.

- 1994–1995: The 1994 economic crisis in Mexico. A speculative attack and default on Mexican debt.

- 1997–1998: The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis. Currency devaluations and banking crises across Asia.

- 1998: The 1998 Russian financial crisis.

The 2000s and Beyond

- 1999–2002: The Argentine economic crisis (1999-2002).

- 2000–2001: The 2001 Turkish economic crisis.

- 2001: The bursting of the dot-com bubble.

- 2007–2008: The Global financial crisis of 2007–2008.

- 2008–2011: The Icelandic financial crisis.

- 2008–2014: The 2008–2014 Spanish financial crisis.

- 2009–2010: The European debt crisis.

- 2010–2018: The Greek government-debt crisis.

- 2013–present: The Ongoing Venezuelan economic crisis.

- 2014: The 2014 Brazilian economic crisis.

- 2014–2016: The Russian financial crisis.

- 2018–present: The Ongoing Turkish currency and debt crisis.

- 2019–present: The Ongoing Sri Lankan currency and debt crisis.

- 2019–present: The Ongoing Lebanese liquidity crisis.

- 2020: The 2020 stock market crash (especially Black Monday and Black Thursday).

- 2022: The Russian financial crisis.

- 2022–present: The Ongoing Pakistani currency and debt crisis.

|

See also

In Spanish: Crisis financiera para niños

In Spanish: Crisis financiera para niños

- Bailout

- Bank run

- Credit crunch

- Financial stability

- Flight-to-liquidity

- Global debt levels

- Kondratiev waves

- Lender of last resort

- Liquidity crisis

- Macroprudential policy

- Nikolai Kondratiev

- Real estate bubble

Specific:

- 2000s energy crisis

- 2007–2008 world food price crisis

- Great Depression

- Subprime mortgage crisis

- America's Great Depression

- Great Trade Collapse

Literature

General perspectives

- Walter Bagehot (1873), Lombard Street: A Description of the Money Market.

- Charles P. Kindleberger and Robert Aliber (2005), Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005 ISBN: 978-1-4039-3651-6).

- Gernot Kohler and Emilio José Chaves (Editors) "Globalization: Critical Perspectives" Hauppauge, New York: Nova Science Publishers ISBN: 1-59033-346-2. With contributions by Samir Amin, Christopher Chase Dunn, Andre Gunder Frank, Immanuel Wallerstein

- Hyman P. Minsky (1986, 2008), Stabilizing an Unstable Economy.

- Joachim Vogt (2014), Fear, Folly, and Financial Crises – Some Policy Lessons from History, UBS Center Public Papers, Issue 2, UBS International Center of Economics in Society, Zurich.

Banking crises

- Franklin Allen and Douglas Gale (2007), Understanding Financial Crises.

- Charles W. Calomiris and Stephen H. Haber (2014), Fragile by Design: The Political Origins of Banking Crises and Scarce Credit, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Jean-Charles Rochet (2008), Why Are There So Many Banking Crises? The Politics and Policy of Bank Regulation.

- R. Glenn Hubbard, ed., (1991) Financial Markets and Financial Crises.

- Luc Laeven and Fabian Valencia (2008), 'Systemic banking crises: a new database'. International Monetary Fund Working Paper 08/224.

- Thomas Marois (2012), States, Banks and Crisis: Emerging Finance Capitalism in Mexico and Turkey, Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, Cheltenham, UK.

Bubbles and crashes

- Dutton, Roy (2010), Financial Meltdown 2010 (Hardback). Infodial. ISBN: 978-0-9556554-3-2

- Charles Mackay (1841), Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds

- Didier Sornette (2003), Why Stock Markets Crash, Princeton University Press.

- Robert J. Shiller (1999, 2006), Irrational Exuberance.

- Markus Brunnermeier (2008), 'Bubbles', New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd ed.

- Douglas French (2009) Early Speculative Bubbles and Increases in the Supply of Money

- Markus K. Brunnermeier (2001), Asset Pricing under Asymmetric Information: Bubbles, Crashes, Technical Analysis, and Herding, Oxford University Press. ISBN: 0-19-829698-3.

International financial crises

- Acocella, N. Di Bartolomeo, G. and Hughes Hallett, A. [2012], ‘Central banks and economic policy after the crisis: what have we learned?’, ch. 5 in: Baker, H.K. and Riddick, L.A. (eds.), ‘Survey of International Finance’, Oxford University Press.

- Paul Krugman (1995), Currencies and Crises.

- Craig Burnside, Martin Eichenbaum, and Sergio Rebelo (2008), 'Currency crisis models', New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd ed.

- Maurice Obstfeld (1996), 'Models of currency crises with self-fulfilling features'. European Economic Review 40.

- Stephen Morris and Hyun Song Shin (1998), 'Unique equilibrium in a model of self-fulfilling currency attacks'. American Economic Review 88 (3).

- Barry Eichengreen (2004), Capital Flows and Crises.

- Charles Goodhart and P. Delargy (1998), 'Financial crises: plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose'. International Finance 1 (2), pp. 261–87.

- Jean Tirole (2002), Financial Crises, Liquidity, and the International Monetary System.

- Guillermo Calvo (2005), Emerging Capital Markets in Turmoil: Bad Luck or Bad Policy?

- Barry Eichengreen (2002), Financial Crises: And What to Do about Them.

- Charles Calomiris (1998), 'Blueprints for a new global financial architecture'.

The Great Depression and earlier banking crises

- Murray Rothbard (1962), The Panic of 1819

- Murray Rothbard (1963), America`s Great Depression.

- Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz (1971), A Monetary History of the United States.

- Ben S. Bernanke (2000), Essays on the Great Depression.

- Robert F. Bruner (2007), The Panic of 1907. Lessons Learned from the Market's Perfect Storm.

Recent international financial crises

- Barry Eichengreen and Peter Lindert, eds., (1992), The International Debt Crisis in Historical Perspective.

- Lessons from the Asian financial crisis / edited by Richard Carney. New York, NY : Routledge, 2009. ISBN: 978-0-415-48190-8 (hardback) ISBN: 0-415-48190-2 (hardback) ISBN: 978-0-203-88477-5 (ebook) ISBN: 0-203-88477-9 (ebook)

- Robertson, Justin, 1972– US-Asia economic relations : a political economy of crisis and the rise of new business actors / Justin Robertson. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY : Routledge, 2008. ISBN: 978-0-415-46951-7 (hbk.) ISBN: 978-0-203-89052-3 (ebook)

2007–2012 financial crisis

- Robert J. Shiller (2008), The Subprime Solution: How Today's Global Financial Crisis Happened, and What to Do About It. ISBN: 0-691-13929-6.

- JC Coffee, ‘What went wrong? An initial inquiry into the causes of the 2008 financial crisis’ (2009) 9(1) Journal of Corporate Law Studies 1

- Markus Brunnermeier (2009), 'Deciphering the liquidity and credit crunch 2007–2008'. Journal of Economic Perspectives 23 (1), pp. 77–100.

- Paul Krugman (2008), The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008. ISBN: 0-393-07101-4.

- "The myths about the economic crisis, the reformist left and economic democracy" by Takis Fotopoulos, The International Journal of Inclusive Democracy, vol 4, no 4, Oct. 2008.

- United States. Congress. House. Committee on the Judiciary. Subcommittee on Commercial and Administrative Law. Working families in financial crisis : medical debt and bankruptcy : hearing before the Subcommittee on Commercial and Administrative Law of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, One Hundred Tenth Congress, first session, 17 July 2007. Washington : U.S. G.P.O. : For sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. G.P.O., 2008. 277 p. : ISBN: 978-0-16-081376-4 ISBN: 016081376X [1]

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |