British credit crisis of 1772–1773 facts for kids

The British credit crisis of 1772–1773 was a major money problem that started in London. It quickly spread to Scotland and the Dutch Republic (which is now the Netherlands). People also called it the crisis of 1772 or the panic of 1772. This was a financial crisis that happened during peacetime. It's often seen as the first big banking crisis that the Bank of England had to deal with.

At this time, new colonies needed a lot of money to grow. This led to a fast increase in how much credit was available and how many banks there were. People started taking big risks with their money, hoping to get rich quickly. They would buy shares (parts of a company) using borrowed money, which was very risky.

In June 1772, a man named Alexander Fordyce lost a huge amount of money, about £300,000, by betting against the East India Company's stock. This meant his business partners were left with massive debts. When this news got out, many banks started to fail. Within two weeks, eight banks in London collapsed. Soon after, about 20 banks across Europe also went out of business. This sudden stop to easy credit hurt the East India Company, the West Indies, and especially the American colonial planters.

Contents

What Happened Before the Crisis?

From the mid-1760s to the early 1770s, it was easy to get credit. This helped factories, mines, and other businesses grow in both Britain and the American colonies. The years 1770 to 1772 seemed good and peaceful for both Britain and America.

Because of the Townshend Act and the end of the Boston Non-importation agreement, Britain sent many more goods to the American colonies. British merchants gave American planters a lot of credit to buy these goods.

However, there were hidden problems. People were taking too many risks, and new, shaky financial companies were popping up. For example, in Scotland, bankers were creating "fake bills of exchange" to make it seem like there was more money available.

One bank, Douglas, Heron & Company, also known as the "Ayr Bank," opened in Ayr, Scotland in 1769. It wanted to increase the money supply. But after it ran out of its own money, it borrowed more by using a long chain of bills from London. This method only helped for a short time and gave people a false sense of hope. Warning signs, like too many goods sitting in warehouses in the colonies, were ignored by both British merchants and American planters.

How London Was Affected

In July 1770, Alexander Fordyce worked with two planters from Grenada. He borrowed 240,000 guilders (Dutch money) from Hope & Co. in Amsterdam. Fordyce was a partner in a London bank called Neale, James, Fordyce and Downe. He made big bets against the East India Company's share price, but his bets went wrong.

Fordyce had gambled away the bank's money. On Monday, June 8, 1772, it became clear that Fordyce had failed. The next day, he ran away to France to avoid paying his debts. He used money from other investments to try and cover his losses. The worst part of the crisis in London happened on June 22, which became known as Black Monday.

The whole City of London was in chaos when Fordyce was declared bankrupt. His belongings and property were taken. His bank, Neale, James, Fordyce, and Down, which was the biggest buyer of Scottish bills, was forced to close.

So many people lost money because of a recent bankruptcy. Because of this, many important merchants and wealthy people met. They decided not to keep their money in any bank that gambled in the stock market. They felt that one bad gamble could ruin hundreds of their customers. This type of gambling cannot be excused for people trusted with others' money, just like gambling at dice tables.

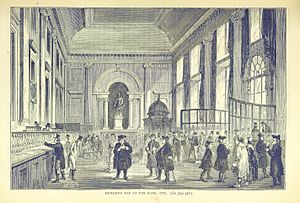

No one knew how bad the situation would get. Economic growth at that time relied heavily on credit, which depended on people trusting the banks. As trust disappeared, the credit system stopped working. Crowds of creditors (people who were owed money) gathered at banks, demanding their money back in cash.

By the end of June, twenty banking houses had gone bankrupt. Many other businesses also struggled. The Gentleman's Magazine said that "No event for 50 years past has been remembered to have given so fatal a blow both to trade and public credit."

In early January 1773, trade and money flow between London and Amsterdam stopped. The Bank of England stepped in to help on Sunday, January 10. They allowed anyone who wanted to take out cash from the bank to do so. Many British merchants quickly sent money to their struggling Dutch partners. The pressure on the Bank of England's money reserves didn't ease until late 1773.

After the crisis, many more businesses went bankrupt. From 1764 to 1771, London had an average of 310 bankruptcies each year. But in 1772, this number jumped to 484, and in 1773, it was 556. Banks that had taken big risks struggled the most. For example, the partners of the Ayr Bank had to pay over £663,397 to pay back their creditors. Because of this, only 112 out of 226 partners were still financially stable by August 1775. On the other hand, banks that had not gambled did not lose money and gained respect for doing well during the difficult time.

In December 1774, Fordyce had to sell his estate to Sir Joshua Vanneck, 1st Baronet. The people who sued him were Hope & Co and Harman and Co..

How Scotland Was Affected

In November 1769, wealthy people in Scotland started the Ayr Bank. This bank was meant to act like a central bank, helping other Scottish banks by lending them money when needed. Like other banks that were limited liability companies, the Ayr Bank could print its own banknotes, which it did a lot.

By 1772, the Ayr Bank had branches in Edinburgh and Dumfries. It also had offices in Glasgow, Inverness, and other towns. Among its 139 shareholders were famous people like the Duke of Buccleuch and the Earl of Dumfries, but no actual bankers.

On June 12, news of the failure of Neale, James, Fordyce and Downe reached Scotland. After the weekend, people rushed to withdraw their money from the Ayr Bank's Edinburgh branch. The Ayr Bank collapsed on June 24. It had lent too much money to colonial planters. This caused other smaller banks to fail too. People said that Scotland had ten times more paper money than actual gold or silver, compared to England.

The bank's collapse was a big blow to wealthy Scottish landowning families. However, it seemed to affect the Scottish economy only mildly. The Ayr Bank managed to reopen for a short time between September 1772 and August 1773. But a meeting of the partners on August 12 decided to close the company for good. The bank might have helped Scotland's economy grow, but its failure made people lose trust in land banking. This meant gold and silver became the most trusted way to back banknotes.

Adam Smith, a famous economist, wrote in his book The Wealth of Nations: "Being the managers rather of other people's money than of their own, it cannot be well expected, that they should watch over it with the same anxious vigilance with which the partners in a private co-partnery frequently watch over their own." This means that people managing other people's money might not be as careful as they would be with their own.

Andrew William Kerr wrote in his History of Banking in Scotland:

The crisis of 1772, though sharp and damaging at first, passed more quickly than expected... The harvest of 1773 was good, fishing was excellent, cattle trade was busy, and money was cheap. Just as things got better, the dark cloud of war appeared.

How Europe Was Affected

Around 1770, borrowing money using property as security (called mortgaging) became very common. Dutch banking firms like Clifford & Co and Hope & Co. lent money to plantations in places like Suriname, Grenada, and Sint Eustatius. They would combine loans for many plantations into packages, and investors often didn't know exactly what they were putting their money into. They trusted the fund managers.

In December 1772, Clifford & Co, a well-known Amsterdam bank, declared it could not pay its debts. This happened because many of its plantation loans were not being repaid.

The fall of Clifford and Sons, and many others, was blamed by some on the proud and poorly managed actions of the English Bank's directors, supported by the government. This caused trust to disappear. People who had to pay bills of exchange stopped doing so. They refused to trust paper money and demanded their outstanding funds. Since there was more paper money than ready cash, this not only stopped trade but also increased the lack of ready cash. Everyone demanded the debts owed to them.

In January, the Bank of Amsterdam created a special loan system to help struggling merchants. Clifford & Sons eventually broke, followed by other firms like Herman & Johan van Seppenwolde. This shortage of credit greatly affected the Dutch plantation colonies in the West Indies, especially Surinam, where farming relied almost entirely on credit from Amsterdam.

The reason for this failure, like Fordyce in London, was too much speculation in East India stock. This caused a series of further failures and a general crisis throughout Amsterdam. According to Wilson, ‘Conditions... were even worse than in 1763... there was paper enough but no cash; hardly a man on the Bourse or in the bill business could produce 50,000 guilders; credit was non-existent, the circulation of money had stopped and so had the discount business; loans on bonds and goods were scarce, and only a little business was being done on foreign securities. Some houses stood seven to eight hundred guilders in debt.

In Amsterdam, a worse disaster was avoided because precious metals were quickly brought in. In January 1773, Joshua Vanneck and his brother, with Thomas Walpole, helped British merchants send £500,000 in gold and piastre (Spanish coins) to Amsterdam.

A few bankruptcies also affected the economies of Stockholm and St. Petersburg a little later. But overall, the rest of Europe was not as badly hit. The Danish Kurantbanken bank was taken over by the government in March 1773. Hope & Co., a leading bank, suffered from a bad deal and the fall of East India Company stocks. The amount of money exchanged at the Amsterdam Exchange Bank dropped sharply from over 50 million guilders in 1772 to 30 million in 1773. George Colebrooke also went bankrupt.

The East India Company's Troubles

The East India Company was originally a trading company. But it was now in charge of a much larger area in India. Its old way of doing things was not good enough for this big new task. However, at the London Stock Exchange, people still expected the Company to pay higher dividends (money paid to shareholders). Dutch investors, who often put their money into English funds, also shared this hope. This optimism led to a big increase in risky trading of future shares in both London and Amsterdam.

In May 1772, the East India Company's stock price went up a lot. But by summer, the Company's debt suddenly grew very high. In India alone, the company owed £1.2 million. Meanwhile, the risky trading of East India stock had weakened the London money market. The Great Bengal famine of 1770, made worse by the East India Company's actions, meant the company lost a lot of expected money from land. The East India Company suffered huge losses, and its stock price fell sharply. Hope & Co. had invested a lot in East India Company and Bank of England stock. On September 19, the value of its shares dropped by 14%.

The crisis for the East India Company started partly because Isaac de Pinto predicted that peace and lots of money would make East India shares "exorbitant heights" (extremely high). Since leading Dutch banks like Andries Pels and Clifford & Son had invested heavily in East India Company stock, they lost money along with other shareholders. This is how the credit crisis spread from London to Amsterdam.

The Regulating Act of 1773 made big changes to how the East India Company operated. It was joined by the Tea Act 1773. The main goal of the Tea Act was to help the struggling British East India Company sell the huge amount of tea it had in its London warehouses. The company had eighteen million pounds of tea that hadn't been sold. On January 14, 1773, the directors of the East India Company asked the government for a loan and unlimited access to sell tea in the American colonies. Both requests were granted. In August, the Bank of England helped the East India Company with a loan.

How the Thirteen Colonies Were Affected

The credit crisis of 1772 greatly worsened the relationship between people who owed money and people who were owed money in the thirteen American colonies and Britain. This was especially true in the South. The southern colonies grew tobacco, rice, and indigo, which they sent to Britain. They were given more credit than the northern colonies, which produced goods that competed with British ones.

It's estimated that in 1776, British merchants claimed American colonies owed them £2,958,390. The southern colonies owed £2,482,763, which was almost 85% of the total. Before the crisis, a system called "commission trading" was common in the southern plantation colonies. London merchants helped planters sell their crops and sent back goods that the planters wanted to buy. Planters usually got credit for twelve months without interest. After that, they paid 5% interest on any unpaid balance.

News of the crisis in Scotland reached Thomas Jefferson in a letter on July 8, 1772. After the crisis began, British merchants urgently demanded their money back. American planters faced the problem of how to pay these debts. Because of the good economy before the crisis, planters were not ready to pay back large amounts of debt quickly.

As the credit system broke down, bills of exchange were rejected. Almost all the heavy gold was sent to Britain in December 1773. Without credit, planters could not continue growing and selling their goods. Since the whole market was struggling, the falling prices of their goods also made things harder for planters.

The crisis of 1772 also led to problems with the colonial tea market. The East India Company was one of the companies hit hardest by the crisis. It couldn't pay back or renew its loan from the Bank of England. So, the company wanted to sell its eighteen million pounds of tea from its British warehouses to the American colonies.

The East India Company had to sell its tea to the colonies through middlemen. This made its tea expensive compared to tea that was smuggled or grown locally in the colonies.

In May 1773, Parliament put a three pence tax on each pound of tea sold. It also allowed the East India Company to sell tea directly through its own agents. The Tea Act lowered the price of tea and gave the East India Company control over the colonial tea market.

People in Charleston, Philadelphia, New York, and Boston were angry that the British government and the East India Company controlled the tea trade. They protested and rejected the imported tea. These protests eventually led to the Boston Tea Party in December 1773.

By December 1773, bills of exchange were so rare that all the dollars and heavy gold had been sent to Great Britain to pay debts. The crisis made the relationship between the North American colonies and Britain much worse. The British government introduced controversial laws for the colonies to try and fix the crisis. This made the crisis one of the causes of the American Revolutionary War.

|

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |