Proto-Uralic homeland facts for kids

The Proto-Uralic homeland is the place where the people who spoke the original Proto-Uralic language lived a long time ago. This was before their language spread out and split into many different languages we know today, like Finnish, Hungarian, and Samoyedic languages.

Scientists have suggested many different places for this homeland. As of 2022, most experts now agree that the Uralic languages likely started relatively recently, somewhere east of the Ural Mountains.

Contents

Where Did Proto-Uralic Speakers Live?

Europe or Siberia?

For a long time, people thought the Proto-Uralic homeland was near the Ural Mountains. This could be on the European side or the Siberian side. One idea for a Siberian homeland came from how the Samoyedic languages seemed to split off first from the main group. Since Samoyedic languages are mostly found in Western Siberia today, some thought the split happened there.

However, we know that Ugric languages (another branch of Uralic) were spoken on the European side of the Urals earlier. This means a European homeland is also possible. More recently, some experts have looked at how sounds in the language changed. They suggest that the first big split was not between Samoyedic and Finno-Ugric, but between Finno-Permic and a group called Ugro-Samoyedic.

Words for 'bee', 'honey', and 'elm' trees support a European homeland. These words can be traced back to Proto-Uralic if Samoyedic wasn't the first branch to split off.

Clues from Borrowed Words

Recently, clues from loanwords (words borrowed from other languages) have also pointed to a European homeland. Proto-Uralic seems to have borrowed words from Proto-Indo-European. The Proto-Indo-European homeland was rarely located east of the Urals. Proto-Uralic even seems to have been in close contact with Proto-Indo-Iranian. This language group is thought to have started near the Caspian Sea before spreading into Asia.

Some researchers have linked the Proto-Uralic homeland to ancient cultures. For example, the Lyalovo culture (around 5000–3650 BC) has been suggested as the Proto-Uralic homeland. The Volosovo culture (around 3650–1900 BC) was then linked to Proto-Finno-Ugric. These cultures were found in northeastern Europe.

However, other experts, like Jaakko Häkkinen, believe the Volosovo culture's language was not Uralic itself. Instead, it might have been an older language that influenced Uralic. He suggests the Garino-Bor culture as the Proto-Uralic homeland instead.

Around 2300 BC, the Volosovo region was visited by groups from the Abashevo culture. These groups buried their dead in kurgans (burial mounds). They are thought to have spoken an early form of Indo-European. They may have influenced the Volosovo people's language by introducing new words. They also helped bring livestock farming to the southern forest areas.

Some ideas suggested that Pre-Proto-Uralic was spoken in Asia. This was based on how it seemed similar to Altaic languages and possible early connections with Yukaghir languages. However, most experts now agree that any shared words between Uralic and Yukaghir are likely due to borrowing from Uralic into Yukaghir, not a shared ancient origin. This borrowing probably happened much later, around 1000 BC.

Continuity Theories

For a long time, some researchers used archaeological findings to argue for "linguistic continuity." This means they believed that people speaking Uralic languages had lived in the same areas, like Estonia and Finland, for thousands of years. This idea became popular in the 1980s.

The "moderate" continuity theory suggested that Uralic languages in Estonia and Finland could be traced back about 6,000 years. A "radical" or "deep" continuity theory went even further, suggesting the languages had been there for over 10,000 years.

However, this way of thinking has been strongly criticized. The same archaeological evidence was sometimes used to support different, even opposite, ideas. This showed that the method wasn't very reliable. Also, new linguistic studies found that Proto-Saami, Proto-Finnic, and Proto-Uralic languages are much younger than these theories suggested.

Today, most linguists do not believe in these continuity theories. This is because of their problems with how they used evidence and because new language studies contradict them. However, some archaeologists and others might still use these arguments.

Modern Ideas About the Homeland

In the 21st century, new language studies have suggested the Proto-Uralic homeland was possibly near the Kama River. Or, more generally, it might have been close to the Great Volga Bend and the Ural Mountains. One expert, Petri Kallio, agrees with Central Russia but prefers the Volga-Oka region further west.

The spread of Proto-Uralic is thought to have happened around 2000 BC (4,000 years ago). Its earlier stages go back at least one or two thousand years before that. This is much later than the old continuity theories suggested.

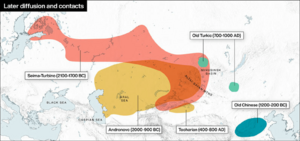

Asko Parpola connects the early Proto-Uralic language with the ancient Elshanka and Kama cultures. He places the homeland in the Kama River valley. He believes Proto-Uralic then spread with the Seima-Turbino material culture. This culture involved a wide trade network for copper and bronze.

Siberian Homeland Ideas

Another idea comes from Juha Janhunen (2009). He argues for a homeland in southern or central Siberia. This could be somewhere between the Ob and Yenisei rivers or near the Sayan Mountains on the Russian–Mongolian border.

This Siberian idea has gained support from other researchers. A team led by Grünthal et al. (2022) found evidence that the Proto-Uralic homeland was east of the Urals, likely in Siberia. They believe it was spoken by local hunter-gatherer groups. The Finno-Ugric languages then spread north and west into the Volga region. The Samoyedic languages went north and east.

They also noted that the Proto-Uralic speakers were "Neolithic." This means they used pottery but didn't have words for farming. They also concluded that Proto-Uralic probably didn't have direct contact with Proto-Indo-European. They believe the idea of shared words between them is not strong.

Rasmus G. Bjørn (2022) also supports a Southern Siberian homeland. He suggests Proto-Uralic speakers might have been part of the ancient Okunev culture in the Altai Mountains region. He notes that contacts between Uralic and other language groups like Tocharian, Indo-Iranian, and Turkic support a homeland near the Altai Mountains.

Jaakko Häkkinen (2023) suggests that the very early stages of Proto-Uralic might have been spoken far away. But he believes the later Proto-Uralic homeland, where the language started to break apart, was in the Central Ural Region. This is based on certain tree names and borrowed words from Indo-Iranian. He thinks the language started to split after 2500 BCE. But the community stayed in a small area until the second millennium BCE. That's when the actual spread of Uralic languages began.

Clues from DNA Studies

Scientists also look at genetics to understand where people came from. Genetic data suggests that early Uralic speakers might be linked to hunter-gatherers in Western and Southern Siberia. These groups seem to have formed from a mix of people from Western and Eastern Eurasia about 7,000–9,000 years ago.

Studies in 2018 and 2019 found that the spread of Uralic languages might be connected to a "Siberian" genetic flow. This flow moved westwards into the Eastern Baltic region. This "Neo-Siberian" expansion happened around 6,000–11,000 years ago. It largely replaced earlier groups in Siberia.

Rasmus G. Bjørn (2022) also connects Proto-Uralic speakers to the ancient Okunevo culture. He suggests that as Indo-Europeans spread east and Northeast Asian groups spread west, they met in the Altai region. This led to early Uralic-speaking groups spreading along the Seima-Turbino trade route. He also notes that this spread matches the frequency of a specific DNA marker called haplogroup N.

Recent studies (Peltola et al. 2023) confirm that modern Uralic-speaking people have different amounts of "Siberian" ancestry. This ancestry is strongest in the modern Nganasan people. This suggests that the Nganasan people, or a historical group like them from the Bronze Age in Southern Siberia, could be a good example of this ancient Siberian source.

See also

- Proto-Uralic language

- Uralic languages

- Finno-Ugric languages

- Samoyedic languages

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |