Restoration spectacular facts for kids

The Restoration spectacular was a special kind of theatre show in England during the late 1600s. These shows were super expensive and needed lots of money, time, fancy sets, and many performers to create. They amazed audiences with exciting action, cool acrobatics, dancing, amazing costumes, detailed scenery, clever paintings that tricked the eye, secret trapdoors, and even fireworks!

Even though people loved them back then, some theatre experts later thought these shows were a bit over-the-top, especially compared to the clever plays of the time. Spectaculars got some ideas from earlier court shows called "masques" and also from French opera. Sometimes, they were even called "English opera." These shows were so different from each other that it's hard for historians to call them just one type of play. Making a spectacular was a huge gamble for theatre companies. If a show failed, the company could end up deeply in debt. But if it was a hit, they could make a lot of money!

Contents

What Made a Show a "Spectacular"?

Many plays in the 1600s had music, dancing, and scenery. But a true "spectacular" was on a whole different level! Experts say there were only about eight of these huge shows between 1660 and 1700.

What made a show a spectacular?

- It needed a very large number of sets.

- It needed many performers.

- It cost a huge amount of money to create.

- It had the chance to make big profits if it was popular.

- It took a very long time to prepare.

Historians believe these shows needed at least four to six months of planning, building, and rehearsing. That's a lot more than the four to six weeks needed for a regular new play!

Amazing Special Effects

Some theatre experts in the past didn't like these big, fancy shows. They thought they were too expensive and didn't have much taste, focusing only on "scenes, machines, and empty operas." However, people like Samuel Pepys, who wrote a famous diary, clearly loved watching them! Even John Dryden, who criticized them, wrote some of these "machine plays" himself.

One of Dryden's plays, The State of Innocence (1677), was never even performed because the theatre company didn't have the money or the machines for it. This play needed "rebellious angels wheeling in the air" and a "lake of brimstone or rolling fire"! The King's Company's theatre, Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, couldn't handle such effects.

But the "machine house" at Dorset Garden Theatre was perfect for these shows. It belonged to the Duke's Company, who were rivals to the King's Company. When the two companies joined together in the 1680s, Dryden finally got to use Dorset Garden. He then wrote one of the most visually stunning plays of the time, Albion and Albanius (1684–85). Imagine this scene:

The Cave of PROTEUS rises out of the Sea... Through the arches is seen the Sea... in the middle of the Cave is PROTEUS asleep on a rock... ALBION and ACACIA seize on him; and while a symphony is playing, he sinks... and changes himself into a Lion, a Crocodile, a Dragon, and then to his own shape again...

How did they make a crocodile appear on stage? Theatre historians aren't entirely sure! There are no drawings or descriptions of the machines and sets used in public theatres back then. This is because stage effects were like trade secrets. Inventors and theatre owners kept their techniques hidden from their competitors.

We can only guess how these effects worked by reading the stage directions in the plays. Experts believe the Dorset Garden Theatre could fly at least four people at once and had complex trapdoors for "transformations" like Proteus changing shape. The only pictures we have of actual Restoration stage sets are from Elkanah Settle's play The Empress of Morocco. Samuel Pepys' diary also gives us clues about what audiences saw in the 1660s. We know that French and Italian opera scenery inspired the English theatres, especially Thomas Betterton at Dorset Garden.

Theatre Before the Restoration (1625–1660)

In the early 1600s, before the English Civil War, special "scenes" (painted backdrops) and "machines" for flying effects were used in court shows called "masques." These were plays put on for King Charles I and his court. In one masque from 1640, Queen Henrietta Maria even made her entrance "descending by a theatrical device from a cloud"!

By 1639, a playwright named William Davenant got permission from the King to build a large new public theatre. It would have technology for music, scenery, and dancing. But other playwrights didn't like the idea of court-style drama coming to public theatres. Then, in 1642, the Civil War started, and all theatres were closed down.

The Puritan government banned public plays from 1642 to 1660. This was a long break in theatre history, but it didn't completely stop it. People still put on plays in big private homes, sometimes with fancy sets. Davenant even charged money for people to see his opera The Siege of Rhodes at his house. Some actors, like Michael Mohun, secretly performed in London. By the late 1650s, the monarchy was about to return, and playwrights like Davenant started planning their theatre activities again.

Theatre Companies Compete (1660s)

William Davenant, the Showman

When the ban on public performances was lifted in 1660, after King Charles II returned to the throne, he really encouraged theatre. He even took a personal interest in who got permission to put on plays. Two playwrights, Thomas Killigrew and William Davenant, who had been loyal to Charles during his exile, received special royal permission to start new theatre companies.

Killigrew took over a group of experienced actors for his "King's Company." They already had a good start and the rights to perform many classic plays by William Shakespeare and others. Davenant's "Duke's Company" was not as lucky. They had young, new actors and very few play rights. They could only perform shorter, updated versions of Shakespeare's plays and a few of Davenant's own.

However, Davenant was a "brilliant impresario" (a person who organizes and manages shows). He quickly turned things around for his company. He finally made his old dream come true: bringing music, dance, and amazing visual effects to the public stage!

In late 1660, while the Duke's Company was still getting ready, the King's Company put on many popular shows. Their new theatre was already open. Samuel Pepys, who loved plays, called it "the finest playhouse... that ever was in England." He was amazed to see Michael Mohun, "who is said to be the best actor in the world," perform there.

Davenant was behind, but he put all his money into building a new, even better theatre. He also cleverly convinced a rising young star, Thomas Betterton, to leave the King's Company and join his. The public loved Davenant's new theatre.

Moveable Scenery Changes Everything

Davenant's new theatre opened on June 28, 1661. It was the first time "moveable" or "changeable" scenery was used on a British public stage! This meant big painted backdrops and side pieces could slide in and out smoothly, even during a play. The first show was a new version of Davenant's opera The Siege of Rhodes.

This new scenery was such a sensation that King Charles II himself came to see a public theatre show for the first time! The King's Company suddenly found their theatre empty. Pepys wrote on July 4: "I went to the theatre... But strange to see this house, that used to be so thronged, now empty since the opera begun—and so will continue for a while I believe."

The Siege of Rhodes was performed for 12 days straight, which was a huge success for that time! The Duke's Company followed up with four more popular shows "with scenes," all admired by Pepys. The King's Company had no choice but to quickly order their own theatre with changeable scenery. Just seven months after Davenant's theatre opened, Killigrew and his actors started building an even grander theatre. This was the first step in a "spectacle war" of the 1660s!

These new, large theatres were very expensive to build. They were paid for by selling shares in the companies, so the companies needed to make more and more money from ticket sales. Not only the theatres and their machines, but also the painted backdrops, special effects, and fancy costumes were extremely costly. Audiences loved luxurious and fitting sets and clothes. Pepys would even go see a play he didn't like just to enjoy the amazing scenery, like "a good scene of a town on fire."

The companies tried to outdo each other, even though their money was always tight. They knew that all their investments could burn down in a few hours. When the King's Company's theatre burned down in January 1672, with all its scenery and costumes, it was a huge financial disaster they never fully recovered from.

The Duke's Company, run smoothly by Davenant and Thomas Betterton, kept leading the way. The King's Company fell further behind, struggling with money and arguments among its managers and actors. The Duke's Company's biggest and most expensive project was the "machine house" at Dorset Garden. The King's Company simply couldn't afford to build anything like it.

The "Machine Theatre" (1670s)

Dorset Garden Theatre

When Davenant died in 1668, the Duke's Company's ownership was unclear. Thomas Betterton, even though he owned a smaller share, continued to manage the company. He ordered the building of the most elaborate theatre of the time: the Dorset Garden Theatre. It even had an apartment for him on top! The Dorset Garden Theatre quickly became famous and glamorous. We don't know much about how it was built, though some people think Christopher Wren designed it.

French Ideas

The machines and flashy shows at Dorset Garden were greatly influenced by French opera. Paris had some of the most amazing visual and musical stage shows in Europe. Betterton even traveled to Paris in 1671 to learn from a popular show called Psyché. Playwright Thomas Shadwell later said, "For several things concerning the decoration of the play, I am obliged to the French."

French opera groups also visited London, which made London audiences very interested in opera. The King's Company, almost broke after their theatre burned down, invited a French musician to perform his opera Ariadne at their new theatre in Drury Lane.

The Duke's Company responded with a huge Shakespearean show at Dorset Garden: Shadwell's version of Tempest. This play was made to show off the new machines:

The Front of the Stage is open'd... the Curtain rises, and discovers a new Frontispiece... Behind this is the Scene, which represents a thick Cloudy Sky, a very Rocky Coast, and a Tempestuous Sea in perpetual Agitation. This Tempest... has many dreadful Objects in it, as several Spirits in horrid shapes flying down amongst the Sailers... And when the Ship is sinking, the whole House is darken'd, and a shower of Fire falls upon 'em. This is accompanied with Lightning, and several Claps of Thunder...

This huge display of effects right at the start of the play was meant to shock the audience and give them a taste of what was to come!

Dorset Garden's Special Shows

The amazing machines at Dorset Garden were rarely used for regular comedies. While most serious plays had some fancy scenes, the plays built for Dorset Garden were a special type. They focused on myths, were huge in scale, and cost a lot of money.

Because of the huge resources needed, only five "machine plays" were produced in the 1670s:

- Davenant's Macbeth (1672–73)

- Settle's Empress of Morocco (1673)

- Shadwell/Dryden/Davenant's Tempest (1673–74)

- Thomas Shadwell's Psyche (1674–75)

- Charles Davenant's Circe (1676–77)

Even though there were only a few, these plays were super important for the Duke's Company's money!

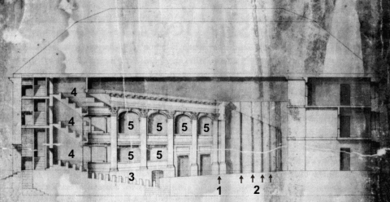

Psyche had not just one, but two, detailed sets for each of its five acts. For example, the start of Act 3 showed: The Scene is the Palace of Cupid... At a good distance are seen three Arches... Through these Arches is seen another Court, that leads to the main Building, which is at a mighty distance. All the Cupids, Capitals and Enrichments of the whole Palace are of Gold. Here the Cyclops are at work at a forge... The Musick strikes up, they dance, hammering the Vases upon Anvils.

This use of perspective scenery and many arches created the illusion that the first court was "at a good distance" and the next "at a mighty distance." This trick of making things look far away was a favorite of Shadwell's.

These shows used many more performers, especially dancers, than other plays of the time. The dancers were paid well and would play many roles. For example, they might be Cyclops in one scene and then quickly change costumes to become townspeople in the next!

Each of these shows was a big financial risk for the theatre companies. The scenery alone for Psyche cost more than £800! To give you an idea, the company's total ticket sales for a whole year were about £10,000. Ticket prices for these special shows were raised to up to four times the normal price.

Both Psyche and The Tempest complained about their high production costs in their closing speeches. They hinted that the audience should reward the "poor players" for taking such risks and for offering amazing sights usually only seen by royalty:

- We have stak'd all we have to treat you here,

- And therefore, Sirs, you should not be severe.

- We in one Vessel have adventur'd all;

- The loss, should we be Shipwrack'd, were not small.

- ...

- Poor Players have this day that Splendor shown,

- Which yet but by Great Monarchs has been done.

The audience seemed to agree! They were amazed by sights like Venus rising into the heavens and "being almost lost in the clouds," followed by Cupid flying up to her chariot, and then Jupiter appearing on a flying eagle. Psyche ended up making a lot of money. In general, the shows in the 1670s made a profit, but those in the 1680s and 1690s barely broke even or were financial disasters.

Funny Parodies

Even after the King's Company got their new theatre in Drury Lane in 1674, they couldn't fully use it. They didn't have enough money to put on their own big spectaculars. Instead, they tried to make money by creating funny parodies of the Duke's Company's most successful shows. These parodies were written by Thomas Duffett.

We don't have all the details about these parodies, but the written versions are very funny to read today. One parody, The Empress of Morocco, made fun of Settle's Empress of Morocco and the Duke's Company's fancy Macbeth show. In Duffett's parody, three witches flew over the audience on brooms, and then a character called Hecate came down over the stage "in a glorious chariot, adorned with pictures of hell and devils, and made of a large wicker basket"! Another parody, The Mock Tempest, made the "shower of fire" from the original Tempest even funnier by having it rain "fire, apples, nuts"!

Political Shows (1680s)

During a time of political trouble in England (1678–84), people didn't invest much in spectaculars. In 1682, the two theatre companies merged. This meant that Dryden finally had access to Dorset Garden's amazing machines. He quickly changed his mind about "spectacle" being superficial and wrote a very visual and extravagant play called Albion and Albanius (1684–85). Remember the cave of Proteus rising from the sea? That was from this play!

Another scene showed Juno, a goddess, in her flying peacock machine: The Clouds divide, and JUNO appears in a Machine drawn by Peacocks; while a Symphony is playing, it moves gently forward, and as it descends, it opens and discovers the Tail of the Peacock, which is so large, that it almost fills the opening of the Stage between Scene and Scene.

This play also had unusual political messages. For example, it showed a figure representing a political leader named Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury "with fiend's wings, and snakes twisted round his body."

Sadly for the theatre company, King Charles II died while Dryden's play was being prepared. James II became king, and a rebellion started. On June 3, 1685, the day the play opened, the Duke of Monmouth landed in the west of England, starting the rebellion. Because "The nation being in a great consternation" (meaning everyone was very worried), the play was only performed six times. It didn't even make half the money it cost to produce, which put the company deeply in debt. This huge failure stopped all new investments in big opera-style shows until things calmed down after the Glorious Revolution in 1689.

The Rise of Opera (1690s)

In the early 1690s, Thomas Betterton continued to manage the United Company. He had a huge budget, like a modern movie director! He staged three true operas of the Restoration spectacular type, all with music by Henry Purcell:

- Dioclesian (1689–90)

- King Arthur (1690–91)

- The Fairy-Queen (1691–92), based on Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream

The show Dioclesian was full of monsters, dragons, and machines. It was very popular throughout the 1690s and made good money for the company. Dryden's King Arthur was considered a real artistic success, with Purcell's music fitting perfectly into the play.

However, at the very end of this period, the costs of the Restoration spectaculars got out of control. The amazing production of The Fairy Queen in 1691–92 was a huge success with audiences. But it was so packed with special effects and so expensive that the company couldn't make a profit! As the old theatre manager Downes remembered, "Though the court and town were wonderfully satisfied with it... the expenses in setting it out being so great, the company got little by it." This show famously included a twelve-foot-high working fountain and six dancing real live monkeys!

The big, fancy spectacular plays became less common during the Restoration period. But amazing stage shows continued in England as Italian "grand opera" became popular in London in the early 1700s. The financial struggles of the Restoration machine plays taught theatre owners a lesson. They learned to create shows with lots of surprising effects and scenes, like silent pantomimes, without needing expensive music, playwrights, or large casts.

Today, there have been a few attempts to bring back the feel of the Restoration spectacular in modern movies. For example, Terry Gilliam's The Adventures of Baron Munchausen starts with what might be the most accurate recreation of the painted scenery, machines, and lighting effects from that time.

Images for kids

-

A view of Rhodes, designed by Inigo Jones' pupil John Webb, to be painted on a backdrop for the first performance of Davenant's opera The Siege of Rhodes "in recitative music" in 1656

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |