Revolt of Ghent (1539–1540) facts for kids

The Revolt of Ghent was an uprising by the people of Ghent against their ruler, Charles V. He was the Holy Roman Emperor and also the King of Spain. This revolt happened in 1539. The citizens were upset about very high taxes. They felt these taxes were only being used to pay for Charles V's wars in other countries, especially a war in Italy (the Italian War of 1536–1538). The next year, Charles V marched his army into Ghent. The rebels gave up without a fight. Charles V then shamed the rebel leaders by making them parade in undershirts with ropes around their necks. Because of this, people from Ghent are still informally called "noose bearers" today.

Contents

Why the Revolt Happened: The Background

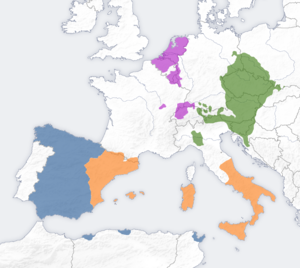

At this time, Ghent was part of the lands ruled by Charles V. However, his sister, Mary of Hungary, was actually in charge of the area. Ghent was located in a region called the Burgundian Circle within the Holy Roman Empire. Ghent and the surrounding Low Countries were very important for trade and business. This made them a big source of money for Charles V. Ghent also had strong business connections with France. The city of Ghent had a large population, with about 40,000 to 50,000 people living there.

In 1515, Charles V introduced a new rule called the Calfvel edict. This rule stopped the city's trade groups, called guilds, from choosing their own leaders.

In 1536, Charles V went to war with the French king, Francis I. They were fighting over control of northern Italy. Charles V asked his sister Mary to gather money and soldiers from the Dutch provinces. In March 1537, Mary announced a huge tax of 1.2 million guilders (a type of money) and asked for an army of 30,000 soldiers. The region of Flanders, where Ghent was located, had to pay one-third of this money. Ghent itself was asked to contribute 56,000 guilders. However, Ghent was already deeply in debt from fines given to them by previous rulers.

Ghent refused to pay these new taxes. They argued that old agreements with past rulers meant no tax could be placed on Ghent without their agreement. They did offer to provide soldiers instead of money. Mary tried to negotiate with Ghent's leaders, but Charles V insisted that Ghent must pay its share without any conditions.

Ghent was the only one of the four Dutch provinces to refuse the new taxes. When the other provinces would not support Ghent, the city secretly offered to join the French king Francis I. They hoped he would protect them from Charles V. However, Francis I turned down Ghent's offer. He might have done this because Charles V had hinted that he might give Francis control over a city called Milan if he cooperated.

In early 1539, Ghent held a very fancy festival. Charles V's officials were angry about how much money was spent on the festival. This was because Ghent had claimed it could not afford to pay its taxes.

In July 1539, rumors spread that some city officials had changed important documents in the city's records. These documents were believed to prove Ghent's right to govern itself. The guilds were especially upset about a document called the "Purchase of Flanders." This legendary paper supposedly gave Ghent the right to refuse all taxes. The guilds believed that their city's history and rights had been changed and misrepresented.

The Uprising: The Revolt Begins

On August 17, 1539, several guilds, including millers, shoemakers, blacksmiths, and shipbuilders, made strong demands. They wanted the right to choose their own leaders. They also demanded the arrest of the city's officials, who they believed had given in to Mary's tax demands against the people's wishes. Over the next few days, the guilds armed themselves and took control of the city. They forced the city officials to either run away or be put in prison. On August 21, they formed a group of nine men to manage the city's affairs.

On August 28, a 75-year-old retired official named Lieven Pyn was executed. He was accused of changing documents that proved Ghent's independence. Pyn had been involved in the tax talks back in 1537. He suffered greatly before his death. On September 3, the old document called the Calfvel was publicly torn apart.

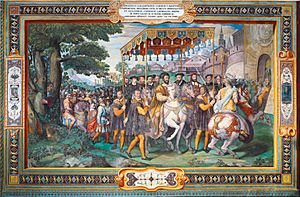

As a sign of friendship, Francis I told Charles V that Ghent had offered to join him. Seeing that the French king was cooperating, Charles V decided it was time to stop the revolt himself. He asked to travel through French land, and Francis I agreed. Charles V did not want to sail to Flanders because he was afraid the English might try to capture him in the Channel. Charles V left Spain with about a hundred people. He traveled through France during the winter of 1539. On December 12, he met with Francis I in a town called Loches, and Francis I went with him to Paris. Charles V then continued his journey, reaching Valenciennes in January. There, he met his sister Mary and a group of people from Ghent. Charles V warned them that he would make an example of Ghent.

Charles V arrived in his lands in late January. He met up with soldiers he had called from Germany, Spain, and the Netherlands. Charles V reached Ghent on February 14 with an army of about 5,000 soldiers. The city did not fight back when he entered.

What Happened Next: The Aftermath

The leaders of the revolt were arrested, and 25 of them were executed. The rest were shamed publicly. On May 3, they were forced to march through the streets from the town hall to Charles V's palace, the Prinsenhof. The procession included all the city's officials and 30 noblemen dressed in black robes and barefoot. There were also 318 guild members and 50 weavers, also in black robes. Finally, 50 day laborers wore white shirts with ropes around their necks. The rope showed that they deserved to be hanged. At the Prinsenhof, they had to beg Charles V and Mary for mercy.

The city was also forced to pay a large fine of 8,000 guilders. In late April, Charles V created a new set of rules called the Caroline Concession. This took away all of Ghent's old legal and political freedoms. It also took away all their weapons. The weavers and 53 other craft guilds were combined into 21 larger groups. The special rights of almost all guilds were removed, except for the shippers and butchers.

The old abbey of Saint Bavo's and its church were torn down. In their place, a new fortress called the Castle of the Spaniards (Spanjaardenkasteel) was built. This fortress held a permanent group of soldiers. Eight of the city's gates and parts of its walls were also destroyed. From then on, the city's officials would be chosen by judges appointed by Charles V's representatives. Charles V also ordered that festivals that made the city proud should be made smaller. The work clock in the belfry was taken down. This clock was a symbol of defiance because it had been used to call workers to meetings in the city's main square.

The Legacy of the Revolt

Since this event, the people of Ghent have been called "noose bearers" (stroppendragers in Dutch). Every summer during the Ghent Festivities, a group called the Guild of Noose Bearers remembers the revolt. They parade through the streets dressed in white shirts with ropes around their necks. The noose has also become an informal symbol of Ghent itself.

See also

In Spanish: Revuelta de Gante (1539) para niños

In Spanish: Revuelta de Gante (1539) para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |