Ross Granville Harrison facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ross Granville Harrison

|

|

|---|---|

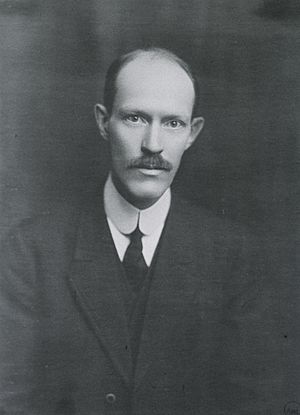

Harrison in 1911

|

|

| Born | January 13, 1870 Germantown, Pennsylvania, U.S.

|

| Died | September 30, 1959 (aged 89) New Haven, Connecticut

|

| Citizenship | American |

| Alma mater | Johns Hopkins University (BA 1889, PhD 1894) University of Bonn (MD 1899) |

| Known for | tissue culture |

| Awards | Fellow of the Royal Society |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | biology and anatomy |

| Institutions | Bryn Mawr College(1894–1985) Yale (1907–1938) |

| Doctoral students | John Spangler Nicholas |

| Signature | |

Ross Granville Harrison (born January 13, 1870 – died September 30, 1959) was an American scientist. He was a biologist and an anatomist. He is famous for his groundbreaking work on growing animal tissues outside the body. This helped us understand how living things develop from tiny beginnings. Harrison studied all over the world and became a respected university professor. He was also part of many important science groups and received several awards for his contributions to biology.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Ross Granville Harrison grew up in Baltimore, Maryland. His family moved there from Germantown, Philadelphia. When he was a teenager, he decided he wanted to study medicine.

In 1886, at age 16, he went to Johns Hopkins University. He earned his first degree, a Bachelor of Arts (BA), in 1889. In 1890, he worked at the United States Fish Commission in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. There, he studied how oysters develop from eggs. He worked with his friends E. G. Conklin and H. V. Wilson.

Harrison also traveled to Germany to study. He worked in Bonn several times between 1892 and 1898. He earned his medical degree (M.D.) there in 1899. In 1894, he received his Ph.D. (a higher degree) after studying physiology and how living things are formed. He also studied math, astronomy, and old languages like Latin and Greek.

His Career in Science

Between his studies in Germany, Harrison taught at Bryn Mawr College from 1894 to 1895. He worked with another famous scientist, T. H. Morgan.

From 1896 to 1907, he taught at Johns Hopkins University. He taught about cells and how embryos develop. During this time, he wrote many important papers. His work on growing tissues outside the body became very important in science.

In 1907, Harrison moved to New Haven, Connecticut. He became a professor at Yale University. He was put in charge of the zoology department in 1912. He helped to improve and reorganize different science departments at Yale. In 1913, he was chosen to be a member of the National Academy of Sciences.

Harrison also helped open the Osborn Memorial Laboratory at Yale in 1913. He became its director in 1918. He was a main advisor for staffing the Medical School in 1914. He continued to teach and lead at Yale until he retired in 1938.

Other Important Work

Besides his university work, Harrison was involved in many other scientific activities. From 1904 to 1946, he was the editor of a science magazine called the Journal of Experimental Zoology. He was also a member of several important science groups, like the American Society of Anatomists and the American Society of Zoologists.

After he retired from Yale, the U.S. government often asked for his advice. He was very good at organizing things. He helped connect scientists, the government, and the media. He was the Chairman of the National Research Council from 1938 to 1946. In this role, he helped people get important medicines like penicillin.

Harrison received many awards for his work. These included the John Scott Medal in 1925 and the John J. Carty Medal in 1947. He also served on the board of trustees for Science Service, which is now called Society for Science & the Public.

Amazing Discoveries in Embryology

One of Harrison's biggest achievements was successfully growing frog nerve cells outside the body. He used a special liquid called lymph. This showed that nerve fibers can grow on their own, without needing a path or connection. It also proved that tissues can be grown outside a living body. He published these amazing results in 1907.

This work was a first step towards today's research on stem cells. Even though Harrison didn't continue this specific research, he encouraged others to do so. His work on how nerve cells grow helped us understand the nervous system much better. It also helped develop techniques for transplanting tissues in surgery.

During World War I, Harrison studied how embryos develop and how their parts become symmetrical. He did experiments with salamander embryos. He would carefully cut out tiny limb buds (the beginnings of limbs) and move them. He found that the main directions of a developing limb are decided at different times. For example, whether a limb will be a front or back limb is decided before whether it will be a top or bottom limb.

Harrison discovered that even if he transplanted half a limb bud, it could still grow into a normal limb. This meant that the surrounding cells in the embryo helped guide the development. However, he also found that if he moved a left limb bud to the right side of the body, it would still grow into a left limb. This showed that some information about the limb's identity was already in the limb bud itself.

Harrison concluded that limb development is not just controlled by the limb bud or by the surrounding environment. Instead, both factors work together to shape how an embryo develops. He published these important findings in 1921.

Personal Life

Ross Harrison married Ida Lange in Germany in 1896. They had five children together. One of their children, Richard Edes Harrison, became a famous mapmaker.

Harrison was a quiet person and didn't enjoy giving many lectures. He preferred to organize, publish his work, and do careful experiments. His drawings for textbooks were highly praised. He loved walking throughout his life. He passed away in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1959.

See also

- Alexander Gurwitsch

- Hans Spemann

- Paul Alfred Weiss

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |