Royal Navy ranks, rates, and uniforms of the 18th and 19th centuries facts for kids

The Royal Navy's ranks, rates, and uniforms in the 1700s and 1800s show how the British Navy created a clear system for its sailors and officers. This system helped everyone know their place, both on ships and on land. Before this, there weren't many rules about what people wore or what their exact job titles were.

Contents

- How Royal Navy Ranks and Uniforms Began

- Royal Navy Jobs and Roles

- How Sailors and Officers Moved Up in Rank

- How Ships Were Organized for Work

- Royal Navy Uniforms Through the Years

- 1748–1767: The First Uniforms

- 1767–1774: Simpler Uniforms

- 1774–1787: New Dress Uniforms

- 1787–1795: Warrant Officers Get Uniforms

- 1795–1812: Epaulettes Arrive

- 1812-1827: White Returns

- 1825-1827: The Undress Tailcoat

- 1827-1830: Uniform Simplification

- 1830-1843: Scarlet Facings

- 1843-1846: White Returns Again

- 1846-1856: Double-Breasted Frock Coat

- After 1856: Modern Uniforms Begin

- Flag Officers: The Admirals

Before the 1740s, sailors and officers in the Royal Navy didn't have official uniforms. Officers usually wore expensive clothes, often dark blue, to show their high social standing. These coats sometimes had gold designs. At first, there were only three main jobs on a ship: the captain, the lieutenant, and the master. This was because, a long time ago, the captain and lieutenant were in charge of the soldiers on the ship, while the master was in charge of sailing the ship itself.

Over time, these two roles combined. The captain and lieutenant became "commissioned officers," meaning they got their jobs directly from the King or Queen. The master became a "warrant officer," someone with special skills in navigation and handling the ship.

New Ranks Emerge

In 1758, the rank of midshipman was created. This was for young people training to become officers. Later, in the 1760s, a new role called "master and commander" appeared. This was for a lieutenant who was temporarily put in charge of a smaller ship. By the 1790s, this was shortened to just "commander" and became a permanent rank. The idea of lieutenants commanding smaller ships continued, and this eventually led to the rank of "lieutenant commander."

When Did Uniforms Become Official?

Lord Anson was the first to set rules for naval officers' uniforms in 1748. Officers wanted a special uniform to show they belonged to the Navy. At first, there was a fancy "best uniform" with an embroidered blue coat and white parts, worn with white pants and stockings. There was also a simpler "working uniform" for daily use.

By 1767, these were called "dress" and "undress" uniforms. In 1795, special shoulder decorations called epaulettes were officially added. These epaulette uniforms changed a bit over the years, with the final design appearing in 1846. Then, in 1856, Royal Navy officers started using stripes on their sleeves to show their rank, a system that is still used today.

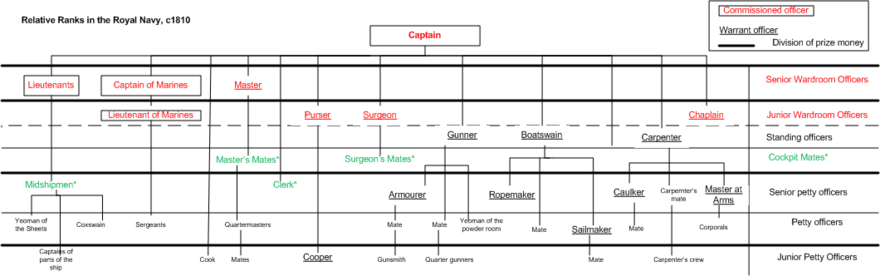

Naval jobs in the 1700s and 1800s were a mix of official ranks, job titles, and informal names used on ships. Uniforms were very important because people who had an official uniform were usually seen as having a higher status, even if their rank wasn't the highest.

Who Was in Charge on a Ship?

In the 1700s Royal Navy, jobs on a ship were based on two things: official ranks and a social difference between "gentlemen" (usually from wealthy families) and "non-gentlemen."

- Commissioned Officers: These were the highest-ranking officers, like the captain and lieutenants, who lived in the "wardroom" (a special area for officers). They were considered gentlemen. Royal Marine officers also fit into this group.

- Warrant Officers: These officers, like the Sailing Master, Purser (who handled money and supplies), Surgeon (doctor), and Chaplain, had special warrants (documents) for their jobs. They usually ate and slept in the wardroom and were often seen as gentlemen. However, the Sailing Master sometimes came from a sailor background, so they might not have been seen as equal socially. All commissioned and warrant officers wore uniforms, though official rules for warrant officers' uniforms came later (1807).

Next were the ship's three "standing officers": the Carpenter, Gunner, and Boatswain (Bo'sun). These skilled seamen were permanently assigned to a ship for its maintenance. They lived with the regular crew and didn't have the same privileges as commissioned or warrant officers if captured.

Young Officers in Training

"Cockpit mate" was a common name for young officers in training who were considered gentlemen. They lived separately from the regular sailors in the "cockpit" area of the ship. This group included midshipmen, who were training to become officers, and master's mates, who were learning from the sailing master. A midshipman was higher in rank than most other petty officers. Young boys hoping to become officers were often called "young gentlemen."

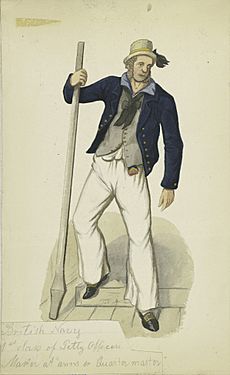

Regular Sailors and Specialists

The rest of the ship's crew lived in the common sleeping areas. This group included petty officers and seamen. Petty officers were skilled sailors who had special jobs on the ship, like sailmaker or quartermaster. They were more educated than common seamen. They didn't have a special uniform, but some ships let them wear a simple blue coat to show their status.

Seamen were divided into two levels: ordinary seaman and able seaman. Sailors were usually part of a "watch" (a group working at a specific time), led by a watch captain. The lowest rank in the Royal Navy was "landsman," given to people, often forced into service, who had little to no experience at sea.

In the 1700s and 1800s, it was common for young boys to start working early. The Royal Navy also hired young boys, who were put into three groups:

- Boy Third Class: Under 15, usually worked as a servant for an officer.

- Boy Second Class: Between 16 and 18, did regular sailor duties.

- Boy First Class: For young gentlemen training to become officers. This was a popular way to gain experience before becoming a midshipman.

Serving as an officer's servant could even count towards the six years of sea time needed to take the test to become a lieutenant. Sometimes, boys were listed as serving on a ship even if they were still at school on land, with high-ranking officers helping them get credit for sea time.

The Navy allowed a certain number of boys on each ship. For example, a large ship might have 19 third-class boys and 13 second-class boys. The youngest were supposed to be at least 13, or 11 if they were an officer's son, but this rule was often broken. The Marine Society, started in 1756, helped poor boys join the Navy by providing food, clothing, and basic sailor training.

Young boys could also get special jobs like a cabin boy (who helped in the kitchen) or a powder monkey (who helped with the ship's cannons). After the age of sailing ships ended, the job of "ship's boy" became an official Royal Navy rank called "boy seaman."

| Job Title | Status | Who Appointed Them | Where They Lived & Ate | Uniform | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commodore | Officer (Commissioned) | Admiralty | Captain's Cabin | Blue coat with gold buttons. | Special rank for captains in charge of several ships. |

| Captain | Commander of the ship. | ||||

| Commander | Blue coat with white vest. | Captain of a smaller ship (full title: "master and commander"). | |||

| Lieutenant | Wardroom (Officers' area) | Officer in charge of a section or a watch. | |||

| Acting lieutenant | Officer (Warrant) | Ship's captain | No set uniform (wore their previous rank's uniform) | Later called sub-lieutenant. | |

| Master | Navy Board | Blue coat with gold Navy buttons | Highest-ranking warrant officer, skilled in navigation. | ||

| Purser | Victualling Board | Ship's accountant, handled supplies. | |||

| Surgeon | Sick and Hurt Board | Ship's doctor. | |||

| Chaplain | Church of England | Only on larger ships. | |||

| Midshipman | Officer in training | Various ways to be appointed | Cockpit (Training area) | Blue coat with white collar patch | Training to be an officer. |

| Midshipman's mate | Officer in training | Blue coat with white trim | Special role for master's mates who passed the lieutenant's exam. | ||

| Master's mate | Could also be called "second master." | ||||

| Surgeon's mate | Sick and Hurt Board | Doctor's assistant on smaller ships. | |||

| Captain's Clerk | Civilian | Usually hired by the captain | Civilian clothes | Did office work on the ship. | |

| School teacher | Only on larger ships. Taught midshipmen. | ||||

| Steward | Crew's living area | A senior cook and servant, usually on larger ships. | |||

| Cook | Usually an older, retired, or injured sailor. | ||||

| Gunner | Standing Officer | Appointed by the captain | Blue coat with Navy buttons | In charge of all ship's weapons. | |

| Boatswain | Most experienced deck sailor. | ||||

| Carpenter | Ship-issued crew clothing | Head of the carpentry team. | |||

| Armourer | Petty Officer | Senior petty officers. | |||

| Ropemaker | |||||

| Caulker | |||||

| Master-at-arms | |||||

| Sailmaker | Mid-level petty officer. | ||||

| Yeoman | Two on board: Yeoman of the sheets & yeoman of the powder room. | ||||

| Coxswain | Deck specialist petty officer. | ||||

| Quartermaster | Steered the ship and served on watch. | ||||

| Cooper | Worked for the purser, made and repaired barrels. | ||||

| Ship's corporal | Assistant to the master-at-arms. | ||||

| Watch captains | Experienced sailor in charge of a watch team. | ||||

| Armourer's mate | Junior petty officer. | ||||

| Gunner's mate | |||||

| Boatswain's mate | |||||

| Caulker's mate | |||||

| Carpenter's mate | |||||

| Sailmaker's mate | |||||

| Quartermaster's mate | |||||

| Gunsmith | Seaman | Seaman specialists. | |||

| Quarter gunner | |||||

| Carpenter's crew | |||||

| Able seaman | Sailor with more than three years of experience. | ||||

| Ordinary seaman | Sailor with at least one year of experience. | ||||

| Landsman | Sailor with less than one year of experience. | ||||

| Boy | Servant | Lowest job on board, usually for boys 12 or younger. |

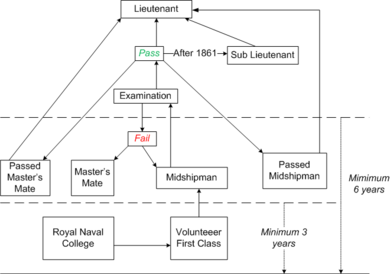

How Sailors and Officers Moved Up in Rank

Moving up in the Royal Navy in the 1700s and 1800s depended on a sailor's starting point.

For Regular Sailors

Most new sailors with no experience started as a "landsman." Very young sailors often began as "cabin boys" or "officers' servants." After a year at sea, a landsman usually became an "ordinary seaman." With three more years and good skills, a sailor could become an "able seaman." For most common sailors, this was as high as they would go. Many spent their entire Navy careers as able seamen.

To become a "petty officer," a sailor needed special technical skills. The ship's captain usually chose who became a petty officer. Sailors could also be listed as a petty officer when a ship was in port looking for a crew. It was expected that sailors would be honest about their skills, as someone pretending to have experience would quickly be found out at sea.

Senior petty officers could also become "standing officers" (boatswain, carpenter, and gunner). These were highly desired jobs because these officers were very skilled. Also, standing officers stayed with a ship and kept getting paid even when the ship was not active, while other officers and crew might be let go and lose their income.

For Officers

"Warrant officers" got their jobs from various official boards. They had almost the same rights and respect as "commissioned officers," including access to the officers' areas of the ship.

To become a commissioned officer, a person needed a royal appointment after passing a special test to become a lieutenant. Most often, people became eligible for this test by serving as a midshipman. However, a master or master's mate could also get this chance.

Once someone became a lieutenant, their rank on board was based on how long they had served (e.g., "1st lieutenant," "2nd lieutenant"). The 1st lieutenant was like the second-in-command. Lieutenants, like regular sailors, had to find ships to serve on. If a lieutenant couldn't find a ship, they were on "half-pay" until they could get a job at sea.

The title of "commander" was originally a temporary job for lieutenants in charge of smaller ships. Successful commanders could hope to be promoted to "captain," which was called "making post." These "post captains" were then assigned to specific types of ships. Once a captain, moving up to "admiral" was based purely on how long they had served. If a captain served long enough for more senior officers to retire or die, they would eventually become an admiral. However, a captain's importance was also judged by the size of the ship they commanded. A captain of a small ship was generally less senior than a captain of a very large ship.

How Ships Were Organized for Work

Royal Navy ships had several ways of organizing people, besides just ranks. The most important was the "watch organization." Watches were groups of sailors who worked 24 hours a day. These were divided into "watch sections," each led by an "officer of the watch," usually a lieutenant, midshipman, or master's mate. The captain and master didn't stand watch but were available at all times.

The main part of the watch system was the "watch teams," each led by a petty officer called a "captain" (this was different from the ship's commanding officer). Most Royal Navy ships had six watch teams: three "deck" teams and three "aloft" teams. The "aloft" teams were made up of skilled sailors called "topmen" who worked high up in the rigging. The six watch teams were:

- Aloft: Fore topmen, main topmen, mizzen topmen

- Deck: Forecastle men, waisters, afterguard

A special watch team of quartermasters handled the ship's navigation and steering from the quarterdeck. Also, the ship's boatswain and his assistants were spread among the watch teams to keep order. Other people on the ship who didn't stand a regular watch included the carpenter's crew and the gunnery teams (who maintained the ship's cannons). Anyone else on board who didn't stand watch was called an "idler," but they still had to report for duty when the "all hands on deck" call was made.

Battle Stations and Ship Conditions

Besides the watch system, ships also had other ways of organizing people. A "division" was a group led by a lieutenant or midshipman, mainly for counting sailors, eating, and sleeping. Divisions were usually only on larger ships.

"Action Stations" was the term for when a Royal Navy ship prepared for battle. This meant all cannons were manned, damage control and medical teams were ready, and senior officers went to the quarterdeck to direct the ship. A sailor's action station was separate from their watch or division, though often groups of sailors at the same action station came from the same division or watch.

A unique condition for some Royal Navy ships was called "in ordinary." These ships were usually permanently docked, with their masts and sails removed, and only a small crew. Ships "in ordinary" didn't have full watch sections and were often used as receiving ships (where new sailors waited for assignment), shore barges, or prison ships.

1748–1767: The First Uniforms

The very first Royal Navy uniforms were only for commissioned officers. They had a blue "dress uniform" (a fancy coat with wide cuffs) and a simpler "frock" uniform for everyday work. The frock coat could be buttoned across the chest to protect the wearer from bad weather. Lieutenants' uniforms were quite plain. Midshipmen only got a frock uniform, which from 1758, had white "turnbacks" on the cuffs, a design still used today. Both uniforms were worn with blue pants and black hats with gold trim.

1767–1774: Simpler Uniforms

In 1767, the fancy "dress uniform" was removed, and the frock became the main uniform. This continued until 1774. Regular sailors still didn't have official uniforms, but ships often gave them standard clothes to make them look more alike.

1774–1787: New Dress Uniforms

In 1774, the old "all-purpose" uniform became the full dress uniform, and a simpler blue "frock" was introduced for daily use. In 1783, high-ranking officers (flag officers) got a new full-dress uniform. For the first time, their rank was shown by stripes on their cuffs: three for Admirals, two for Vice Admirals, and one for Rear Admirals.

1787–1795: Warrant Officers Get Uniforms

In 1787, the fancy cuffs on officers' full-dress uniforms were replaced with white round cuffs. For flag officers, the embroidery was replaced with lace. This year was also important because "warrant officers" (like Masters, Surgeons, Pursers, Boatswains, and Carpenters) were given a standard, plain blue uniform. Midshipmen's cuffs also changed to blue round cuffs.

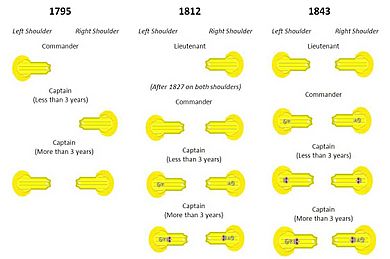

1795–1812: Epaulettes Arrive

The biggest uniform change in the late 1700s happened on June 1, 1795, when flag officers, captains, and commanders were given epaulettes (shoulder decorations). Uniforms for all ranks lost their white parts. For the next 50 years, epaulettes were the main way to tell an officer's rank. Surgeons got their own special uniform in 1805, and pursers and masters got their full-dress uniforms in 1807.

1812-1827: White Returns

From March 1812, the full-dress uniform brought back the white lapels, collars, and cuffs that had been removed in 1795. Midshipmen kept their all-blue jacket, and the captain's uniform became double-breasted. Lieutenants were given a single gold epaulette on their right side. In 1812, the anchor symbol on uniform buttons was topped with a crown.

1825-1827: The Undress Tailcoat

In 1825, the "undress tailcoat" was introduced. This was a blue tailcoat, similar to what civilians wore, and it was worn with epaulettes.

1827-1830: Uniform Simplification

A big change to the full-dress coat happened in 1827. A new style was introduced that looked very much like the undress coat from 1812-1825. The coat tails were cut away at the waist and had to be buttoned up. Midshipmen, Masters, and Surgeons kept their existing uniforms but had to wear them fully buttoned. In 1827, there was no longer a big difference between full dress and undress; officers could just wear plain blue trousers for undress. In 1829, a single-breasted frock coat was allowed for officers to wear near their ships. This coat had sleeve lace to show rank: a braid for midshipmen, two stripes for lieutenants and commanders, and three stripes for captains. Flag officers wore their epaulettes with this coat. This uniform was worn with plain blue trousers and a peaked cap. Even though it was only used for a short time (until 1833), this frock coat was important for later uniform styles.

1830-1843: Scarlet Facings

In 1830, the white parts of the full-dress coat were changed to scarlet. This lasted until 1843.

1843-1846: White Returns Again

In 1843, white parts returned to the full dress uniforms of commissioned officers. Lieutenants were given two plain epaulettes instead of just one.

1846-1856: Double-Breasted Frock Coat

In 1847, a double-breasted frock coat was adopted for undress wear. It had rank lace on the sleeves, similar to earlier frock coats. This could be worn with a peaked cap or with a cocked hat and sword for more formal events. Sleeve stripes were introduced for full dress and on the undress tailcoat for all commissioned officers from 1856.

After 1856: Modern Uniforms Begin

After 1856, uniforms continued to evolve. In 1878, rules for cuff buttons on undress coats were made clearer. In 1880, the "ship jacket" (like today's reefer jacket) was introduced for wear at night or in bad weather. In 1885, a white uniform (tunic, trousers, sun helmet) was introduced for hot climates, and a navy blue tunic and trousers for temperate climates. Rank was first worn on the sleeve for these new tunics. The reefer jacket replaced the blue tunic in 1889. The white tunic was also redesigned, with rank moving to shoulder-boards instead of the sleeve.

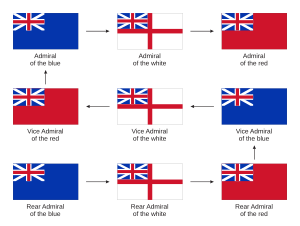

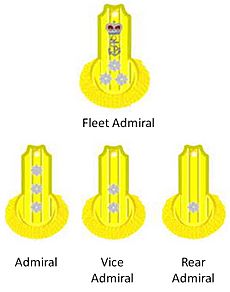

Flag Officers: The Admirals

High-ranking officers, known as "flag officers" (admirals), were promoted based entirely on how long they had served. When a spot opened up on the admirals' list (because someone died or retired), the next captain in line would automatically become a "rear admiral." They would then be assigned to one of three colored squadrons: blue, white, or red.

As more spots opened, the admiral would move up to the same rank in higher squadrons. For example, a rear admiral of the blue squadron would become a rear admiral of the white, then a rear admiral of the red. Once they reached the highest position for that rank (rear-admiral of the red), they would then be promoted to "vice admiral" and start again at the lowest colored squadron (vice-admiral of the blue). This process continued until a vice-admiral of the red became an "admiral of the blue." The highest possible rank was "admiral of the red squadron," which until 1805 was the same as "admiral of the fleet."

Sometimes, admirals would "jump" to a higher rank in a different squadron without serving in every rank of every squadron. For example, William Bligh was promoted directly from rear admiral to vice-admiral of the blue, skipping other steps. However, a higher-ranked admiral in a lower squadron (like a vice-admiral of the blue) could not be demoted to a lower rank in a higher squadron (like a rear admiral of the red).

Some flag officers were not assigned to a squadron and were just called "admiral." These were commonly known as "yellow admirals." Another title was port admiral, which was the senior naval officer in charge of a British port.

|