Saul Alinsky facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Saul Alinsky

|

|

|---|---|

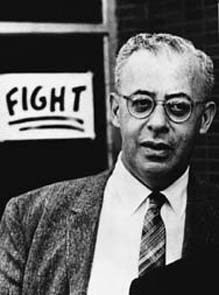

Alinsky in 1963

|

|

| Born |

Saul David Alinsky

January 30, 1909 Chicago, Illinois, U.S.

|

| Died | June 12, 1972 (aged 63) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | University of Chicago (PhB) |

| Occupation | Community organizer, writer, political activist |

|

Notable work

|

Rules for Radicals (1971) |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | Pacem in Terris Award, 1969 |

| Signature | |

|

|

| Notes | |

|

Sources

|

|

Saul David Alinsky (January 30, 1909 – June 12, 1972) was an American community activist and political theorist. He helped poor communities organize to ask for changes from landlords, politicians, and business leaders. His work made him well-known across the country.

In his famous book, Rules for Radicals (1971), Alinsky taught people how to organize. He believed that working together and sometimes even arguing was important for getting social justice. Later, his ideas inspired different political groups, including some on the political Right and some on the political Left.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Growing Up in Chicago

Saul Alinsky was born in 1909 in Chicago, Illinois. His parents were Jewish immigrants from Russia. His father worked as a tailor and later owned a deli.

Saul was very religious until he was about 12 years old. He worried his parents would make him a rabbi. Even though he didn't face much antisemitism himself, he knew it was common. He learned an important lesson from a rabbi: "where there are no men, be thou a man." This meant to be a leader when others aren't.

College and Early Work

In 1926, Alinsky went to the University of Chicago. He studied sociology, which is the study of how people live in groups. His teachers believed that problems like crime in poor areas were caused by how society was organized, not by who people were.

The Great Depression changed Alinsky's plans. He then studied criminology, which is the study of crime. He spent time learning about how power worked. He also worked with young people who had broken the law. He saw that poor housing and unfair treatment often led to crime.

Helping Communities Organize

Starting the Back of the Yards Council

In 1938, Alinsky became a full-time activist. He helped raise money for groups fighting for change. He also worked with labor unions, which are groups that protect workers' rights.

Alinsky wanted to help people in the poorest neighborhoods. He believed they could take control of their own communities. He wanted to teach them how to make changes themselves.

He started in a tough area of Chicago called the Back of the Yards. This area was known from the book The Jungle. With a park supervisor named Joseph Meegan, Alinsky created the Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council (BYNC).

This Council brought together different groups of people who didn't always get along. They worked together to demand better conditions from local businesses and the city. They won important changes for their community.

Alinsky believed that local people should lead these efforts. He said that organizers should help, but the people living there had to make the decisions. This helped residents gain new confidence and resources.

Creating the Industrial Areas Foundation

In 1940, Alinsky started the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF). This was a national group that helped communities organize. The IAF worked with churches and other local groups. Their goal was to train local leaders and build trust among different community members.

For the next 10 years, Alinsky helped communities across the country. He worked to "rub raw the sores of discontent," meaning he helped people see their problems clearly. Then he helped them take action.

Sometimes, these efforts faced challenges. For example, some community councils struggled after the original organizers left. Alinsky also saw that some successful groups, like the Back of the Yards Council, didn't support fair housing for everyone.

He realized that strong, organized groups were needed. In 1959, he decided that Chicago needed a powerful Black community organization. This group could work with other groups to make changes.

Mentoring The Woodlawn Organization

Alinsky helped start The Woodlawn Organization (TWO) in a Black community on Chicago's South Side. TWO was a group of local clubs, churches, and businesses. These groups paid dues, and local leaders ran the organization.

TWO quickly became the voice of the Black neighborhood. They helped develop new leaders, like Arthur M. Brazier. Brazier started as a mail carrier and became a national leader in the Black Power movement.

In 1961, Alinsky helped TWO show its power. They brought 2,500 Black residents to City Hall to register to vote. This showed city leaders that TWO was a strong force.

Through TWO, Woodlawn residents challenged the University of Chicago's plans for their area. Alinsky said TWO was the first group to plan its own urban renewal. They even controlled who got building contracts.

Alinsky believed in using new and creative ways to get things done. When the mayor was slow to fix housing problems, TWO threatened to bring a thousand live rats to City Hall. This was a shocking way to get attention. Alinsky always said you had to keep inventing new tactics to surprise your opponents.

Helping in Rochester, NY

In the 1960s, Alinsky focused on training community organizers through the IAF. He helped Black organizing groups in Kansas City and Buffalo. He also trained leaders like Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta who worked with Mexican Americans in California.

One of Alinsky's biggest projects was in Rochester, New York. After a riot in 1964, local churches and Black civil rights leaders asked Alinsky for help. Rochester was largely controlled by the company Eastman Kodak.

Alinsky helped them create FIGHT (Freedom, Integration, God, Honor, Today). This group pressured Kodak to offer more jobs and to get involved in city government. This was the last Black community Alinsky directly helped organize.

Community Action and the War on Poverty

In the 1960s, the U.S. government started the War on Poverty. This program aimed to help poor communities. It said that local people should be involved in designing anti-poverty programs.

Alinsky believed this was important. He called poverty a "political poverty." He thought that poor people needed their own organized power to make real changes.

However, the government's program changed. City halls gained control over how money was spent. This meant that Alinsky's idea of truly independent, community-led groups wasn't fully supported by federal funds.

Important Ideas and Challenges

Working with Different Groups

Alinsky was sometimes criticized for working with Communists in the 1930s. He said he did so because they were helping workers and Black people. He also supported Russia at that time because it was fighting against Hitler.

However, Alinsky did not like the idea of a government controlling everything from the top down. He believed in democracy where people from the bottom up made decisions. He thought that people were the best ones to decide what was good for their community.

The Black Power Movement

In 1966, the phrase "Black Power!" became popular. Alinsky agreed with the idea of "community power," saying that if a community was Black, then it was "Black Power." He challenged leaders to organize their communities.

He also disagreed with some extreme ideas. He believed in supporting America and working for change within the country. By 1970, he felt that white people should step back from organizing in Black neighborhoods. He thought it was a necessary step for Black communities to lead themselves.

Students and the New Left

In the 1960s, many college students became activists. They wanted to create a "new left" that focused on justice. They also believed in community organizing.

Alinsky met with some of these student leaders. But he thought their ideas were too simple. He believed they were too romantic about poor people. He also thought they focused too much on talking and not enough on strong leadership and action.

He felt that student activists were more interested in "revelation" (showing off) than "revolution" (making real change). He thought their actions often made middle-class people angry, which was a mistake.

Later Life and Impact

Criticisms of Alinsky's Approach

Some critics said that Alinsky's organizing efforts only led to small, local changes. They felt he didn't focus enough on bigger goals or political ideas. They argued that his groups achieved "a better ghetto" but didn't change the larger system.

Alinsky was sensitive to these criticisms. He knew that some of his projects faced big challenges, like poor housing and unemployment. He was open to new ideas, like helping communities get involved in elections.

Death and Family

Saul Alinsky died on June 12, 1972, at age 63. He had a heart attack while walking near his home in California.

Alinsky's parents divorced when he was 18. He remained close to his mother.

He was married three times. His first wife, Helene Simon, died in 1947 trying to save two children. He was very sad about her death. His second wife, Jean Graham, became very ill, and they later divorced. In the year before he died, he married Irene McInnis. He had two children, Kathryn Wilson and Lee David Alinsky.

Alinsky's Lasting Influence

Inspiring Different Groups

In the 2000s, Alinsky's book Rules for Radicals became popular with some conservative groups. They admired his organizing skills, even if they didn't agree with his political goals. Groups like FreedomWorks shared his ideas, and some Tea Party leaders read his book.

Alinsky's name also came up when Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama ran for president. Hillary Clinton had written her college paper about Alinsky. She agreed with some of his ideas but thought that change also needed to happen at higher government levels.

Barack Obama also worked as a community organizer in Chicago. He learned from Alinsky's ideas. However, Obama felt that people's hopes and values were just as important as their self-interest. He also preferred to find ways to connect with people rather than always being confrontational.

The Industrial Areas Foundation Today

Many people say that Alinsky is like the "father" of community organizing. He showed that it could be a lifelong career.

After Alinsky died, Edward T. Chambers became the leader of the IAF. The IAF has trained many community and labor organizers. Famous organizers like Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta were mentored by Fred Ross, who worked for Alinsky.

Other groups, like PICO National Network and Gamaliel Foundation, also follow the IAF's way of organizing. They often work with religious groups to build strong communities.

People's Action and Global Reach

National People's Action (NPA) is another group that uses Alinsky's methods. They work from the "bottom-up," going door-to-door to organize people. NPA showed that Alinsky-style organizing could achieve big national changes, like passing the Community Reinvestment Act in 1977.

In 2016, NPA joined with other groups to form People's Action. This group works to empower poor and working people. They focus on both issue campaigns and elections.

Alinsky's ideas have also spread to other countries. In 1989, Neil Jameson started Citizens UK in England, which helps communities organize and has campaigned for a living wage. In France, groups like Alliance Citoyenne use Alinsky's methods to help people in poor areas have a stronger voice. Similar efforts have also started in Germany.

"Alinskyism" and Modern Activism

Today, activists still discuss Alinsky's legacy. Some say his focus on single issues and local wins might not be enough for big changes. Others defend him, saying he inspires movements like the Occupy movement and climate action groups.

For example, activists from Extinction Rebellion (XR) say Rules for Radicals helps them understand how to create change. They believe in using disruption to get attention, a tactic Alinsky often used.

It's important to know that some quotes about Alinsky circulating online are not true. For instance, some viral images falsely claim he wrote rules for creating a "social state" that equals communism. These quotes are not found in his actual writings.

See also

In Spanish: Saul Alinsky para niños

In Spanish: Saul Alinsky para niños

- Community development

- Community education

- Community practice

- Community psychology

- Critical consciousness

- Critical psychology

- Organization workshop