Schoolmaster snapper facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Schoolmaster snapper |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Perciformes |

| Family: | Lutjanidae |

| Genus: | Lutjanus |

| Species: |

L. apodus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Lutjanus apodus (Walbaum, 1792)

|

|

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The schoolmaster snapper (Lutjanus apodus) is a type of ray-finned fish that lives in the ocean. It belongs to the family of snappers. You can find this fish in the western Atlantic Ocean. Like other snappers, it is a popular fish to eat.

Contents

About the Schoolmaster Snapper

The schoolmaster snapper was first officially described in 1792. A German scientist named Johann Julius Walbaum gave it the name Perca apoda. He named it "apoda," which means "footless," because the drawing he used didn't show its pectoral fins (the fins on its sides). The first place it was found and described was in the Bahamas.

What Does It Look Like?

The schoolmaster snapper has a strong body that is a bit flat from side to side. It has a long, pointed snout and a big mouth. You can see one pair of its upper teeth even when its mouth is closed, as they are larger than the back teeth in its lower jaw.

Its dorsal fin (the fin on its back) is one long fin, but it has a small dip in the middle. This fin has 10 stiff spines and 14 soft rays. The anal fin (underneath the body) is rounded and has 3 spines and 8 soft rays. Its caudal fin (tail fin) is slightly notched or straight. The pectoral fins (side fins) are long and reach past its anus.

This fish is usually olive-gray to brownish on its upper back and sides. Its lower sides and belly are lighter. It doesn't have a dark spot on its side below the front part of its dorsal fin. It often has 8 thin, light stripes going up and down its body. These stripes might fade or disappear as the fish gets older. A blue line, which can be solid or broken, runs under its eye. This line might also disappear as the fish grows. Its fins and tail are bright yellow, yellow-green, or light orange. It also has blue stripes on its snout.

The schoolmaster snapper can grow up to about 79 centimeters (31 inches) long. However, they are usually around 35 centimeters (14 inches) long. The heaviest one ever recorded weighed about 10.8 kilograms (23.8 pounds).

Where Does It Live?

The schoolmaster snapper lives in the western Atlantic Ocean. Its range goes from Bermuda and the southeastern coast of the United States, all the way down to the Bahamas and into the Gulf of Mexico. It also lives throughout the Caribbean Sea.

Sometimes, young schoolmaster snappers are seen as far north as Massachusetts. However, they can't survive the cold winters there. This fish usually lives in water between 1 and 50 meters (3 to 164 feet) deep. One was even found at 89 meters (292 feet) deep!

Adult schoolmaster snappers usually stay close to shore, finding shelter around elkhorn and gorgonian corals. Larger adults can sometimes be found on the continental shelf. They often live in waters up to 4 meters (13 feet) deep. At night, they might swim further out, sometimes visiting seagrass beds.

How It Lives

Schoolmaster snappers often gather in large groups during the day. These groups are like resting schools. At night, they spread out to find food. These groups help protect them from predators, making it harder for any one fish to be caught. These fish spend most of their day swimming (about 84%), some time resting (13%), and a little time eating (2%).

What It Eats

What schoolmaster snappers eat changes as they grow. Smaller fish, less than 70 millimeters (2.8 inches) long, mostly eat tiny crustaceans, like amphipods and crabs.

Bigger schoolmaster snappers prefer to eat smaller fish, which make up more than half of their diet by weight. They also eat crabs, shrimp, and stomatopods (mantis shrimp). These changes in diet happen because bigger fish can open their mouths wider to catch larger prey.

Reproduction and Growth

Schoolmaster snappers have separate males and females. They lay their eggs (spawn) for most of the year, but mostly in the middle to late summer. Off the coast of Cuba, they spawn during April to June.

When they reproduce, both male and female fish release their eggs and sperm into the open water at the same time. The fertilized eggs then sink to the bottom and are not guarded by the parents.

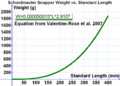

The schoolmaster snapper grows slowly and can live for a long time. The oldest one ever recorded was 42 years old. As these fish grow longer, they also get heavier.

Fishing for Schoolmaster Snappers

People enjoy catching schoolmaster snappers for both fun and food. However, they are not caught as often by commercial fishermen as some other types of snappers. Many people say they taste excellent. But, sometimes, eating this fish can cause a type of food poisoning called ciguatera in humans.

Fishing rules for schoolmaster snappers can be different in each state in the U.S., but they are often similar. For example, in Florida, schoolmaster snappers must be at least 10 inches (25 cm) long to be kept. Fishermen can catch up to 10 snappers per day, but this limit includes all types of snapper.

Fishermen often use light fishing rods with spinning or baitcasting reels to catch schoolmaster snappers. The best natural baits are live shrimp, small baitfish, or pieces of shrimp and cut bait. Artificial lures, like jigs, are sometimes used but are not usually as successful.

Protecting the Schoolmaster Snapper

The IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) lists the schoolmaster snapper as a species of Least Concern. This means it is not currently at high risk of disappearing. This is partly because commercial fishermen don't usually target them, and there aren't many records of how many are caught.

Young schoolmaster snappers are common in mangrove areas and on shallow coral reefs. These habitats can be harmed by new buildings along the coast and by climate change. In some places, like the Rosario Islands in Colombia, illegal fishing with dynamite almost made this species disappear.

To help protect schoolmaster snappers, some areas have rules about how big the fish must be to keep, and how many fish a person can catch. It has also been suggested that "no-take zones" (areas where fishing is not allowed) could help protect these fish. This would reduce how many fish are caught and make their defensive groups less vulnerable to predators.

Images for kids

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |