Sinking of U-864 facts for kids

The German submarine U-864 was attacked and sunk on 9 February 1945 by HMS Venturer, a British submarine of the Royal Navy. Venturer was patrolling the waters around Fedje Island, off the Norwegian coast in the North Sea. This event is special because it was the only time in history that one submarine sank another while both were completely underwater.

Quick facts for kids Action of 9 February 1945 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The Battle of the Atlantic during the Second World War | |||||||

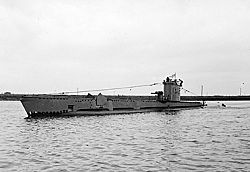

HMS Venturer in August 1943 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| HMS Venturer | U-864 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None | U-864 with all 73 hands |

||||||

Contents

The Story Behind the Attack

The German Submarine: U-864

The U-864 was a German submarine on a secret mission called Operation Caesar. It was heading to Japan during World War II. On February 6, 1945, the U-864 passed by Fedje, Norway. However, one of its engines was making a lot of noise. This loud noise was probably caused by a problem with its machinery.

The captain of U-864, Ralf-Reimar Wolfram, decided to turn back. He wanted to go to the submarine base in Bergen to fix the engine. At this time, many Allied (mostly British) ships and submarines were patrolling the area. The British had also cracked the German secret code, Enigma. They knew that U-864 was carrying important cargo that could help Japan continue the war. So, the British Navy ordered their submarine, Venturer, to find and sink U-864.

The British Submarine: HMS Venturer

When the British learned about the U-864's mission, they sent Venturer to stop it. The captain of Venturer, Lieutenant Jimmy Launders, received a secret message. It told him where German submarines might be traveling.

To avoid being detected by U-864, Launders made a smart choice. He turned off Venturer's ASDIC (sonar system). Instead, he decided to rely only on hydrophones. Hydrophones are like underwater microphones that listen for sounds. This way, Venturer would be quieter while searching.

The Underwater Chase

As Venturer patrolled, its hydrophone operator heard a strange noise. It sounded like a fishing boat's diesel engine. Captain Launders decided to follow the sound. Then, an officer on Venturers periscope saw something above the water. He thought it was another periscope, but it was probably U-864s snorkel.

A snorkel is a tube that allows a submarine to run its diesel engines and get fresh air while still underwater. The snorkel limited the U-864s speed and how deep it could go. The noise from the diesel engines also made U-864s own listening devices less effective. This meant U-864 probably didn't hear Venturer moving slowly with its electric motors.

Captain Launders realized the strange noise was coming from a submerged submarine. He figured out it was U-864. He tracked the German submarine using his hydrophones, hoping it would surface. But U-864 stayed at snorkel depth and moved in a zigzag pattern. This zigzagging was a common way for submarines to avoid attacks.

Launders tracked U-864 for about three hours. It became clear that the German submarine would not surface. Launders had to decide whether to attack before his submarine's batteries ran out. Attacking a submerged submarine was very difficult. It meant calculating the target's position in four ways: time, distance, direction, and depth. This had never been done before because it was considered too hard.

Usually, when a submarine fires torpedoes, it can see its target. It uses a special device to measure the distance and speed of the target. Then, a computer helps aim the torpedo. The depth of the torpedo also needs to be set correctly. If it's too deep, it goes under the target. If it's too shallow, it goes over. But Launders could only guess the depth of U-864.

Captain Launders made all the complex calculations and guesses about U-864's movements. Then, he ordered all four of his front torpedo tubes to fire. He immediately dived deeper to avoid any counter-attack from U-864. The torpedoes were fired with a short delay between each pair and at different depths.

U-864 heard the torpedoes coming and tried to get away. But it was hard for the submarine to move quickly or turn sharply. It took time to pull in the snorkel, turn off the diesel engine, and start the electric motors. The first three torpedoes missed. However, U-864 accidentally steered right into the path of the fourth torpedo. U-864 exploded, broke into two pieces, and sank with everyone on board. It came to rest on the seabed about 490 feet (150 meters) deep.

What Happened Next

The U-864 sank about 31 nautical miles (57 kilometers) from the submarine base in Bergen. Captain Launders received an award called a bar to his Distinguished Service Order (DSO). Several other crew members also received awards. This action was the only naval battle ever fought completely underwater.

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |