Sultana (steamboat) facts for kids

|

|

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Sultana |

| Owner | Initially Capt. Preston Lodwick, then a consortium including Capt. James Cass Mason |

| Port of registry | |

| Route | St. Louis, Missouri, to New Orleans, Louisiana |

| Builder | John Litherbury Boatyard, Cincinnati, Ohio |

| Launched | January 3, 1863 |

| In service | 1863 |

| Fate | Exploded and sank, April 27, 1865, on Mississippi River seven miles north of Memphis, Tennessee. 35°11′26″N 90°6′52″W / 35.19056°N 90.11444°W |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage | 1,719 tons |

| Length | 260 feet |

| Beam | 42 feet |

| Decks | Four decks (including pilothouse) |

| Propulsion | 34 ft (10 m) diameter paddlewheels |

| Capacity | 376 passengers and cargo |

| Crew | 85 |

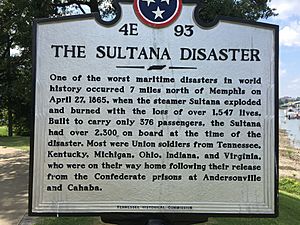

The Sultana was a large paddlewheel steamboat that exploded and sank on the Mississippi River on April 27, 1865. This terrible event killed at least 1,547 people. It remains the worst ship disaster in United States history.

Built in 1863 in Cincinnati, Ohio, the Sultana was made of wood. It was designed to carry cotton on the lower Mississippi River. The ship weighed 1,719 tons and usually had a crew of 85. For two years, it traveled regularly between St. Louis and New Orleans. During the American Civil War, it often carried soldiers. Even though it was built for only 376 passengers, the Sultana was carrying over 2,500 people when three of its four boilers exploded. The ship sank near Memphis, Tennessee. This disaster happened just after the Civil War ended. Other big news, like the killing of President Abraham Lincoln's assassin, John Wilkes Booth, overshadowed it. Because of this, no one was ever held responsible for the tragedy.

Contents

Building the Sultana

The Sultana was launched on January 3, 1863. It was the fifth steamboat to have this name. The ship was built to be fast and carry a lot of cargo. It was 260 feet (79 meters) long and 42 feet (13 meters) wide. Its two large side paddle wheels were powered by four special boilers. These boilers were introduced in 1848 and could make twice as much steam as older types. Each boiler was 18 feet (5.5 meters) long and 46 inches (117 cm) across. They had 24 tubes, called flues, that went from the firebox to the chimney.

These new boilers saved fuel, but they were also more dangerous. The water levels inside them had to be watched very carefully. The spaces between the many flues could easily get clogged with dirt and minerals from the river water. Even a small drop in water level could make parts of the boiler get too hot. This could weaken the metal and greatly increase the chance of an explosion. Steamboats were built with many layers of light, flammable wood. This meant any explosion would likely cause a huge fire.

The Disaster

What Happened Before

The Sultana left St. Louis on April 13, 1865, heading for New Orleans. Captain James Cass Mason was in charge. On April 15, the ship was docked in Cairo, Illinois. News arrived that U.S. President Abraham Lincoln had been shot. Captain Mason quickly took newspapers and headed south. He knew that telegraph communication was mostly cut off due to the recently ended American Civil War.

When the Sultana reached Vicksburg, Mississippi, Captain Reuben Hatch approached Mason. Hatch was the chief quartermaster (a supply officer) in Vicksburg. Thousands of recently freed Union prisoners of war were waiting to go home. They had been held in Confederate prison camps like Cahaba and Andersonville. The U.S. government would pay steamboat captains for each soldier they took north. Hatch offered Mason a deal: if Mason would give him some money, Hatch would make sure the Sultana got a full load of about 1,400 prisoners. Mason needed money, so he quickly agreed.

The Sultana continued to New Orleans, spreading the news of Lincoln's assassination. On April 21, it left New Orleans with about 70 passengers and some livestock. It also had its crew of 85. About ten hours south of Vicksburg, one of the Sultana's four boilers started leaking. The ship had to slow down and limp back to Vicksburg for repairs. It also needed to pick up the promised prisoners.

Bad Boiler Fix

While the freed prisoners were brought to the Sultana, a mechanic came to fix the leaky boiler. The mechanic wanted to cut out the damaged part and replace it. But Captain Mason knew this would take several days. He would lose his chance to carry the prisoners, as they would be sent home on other boats. So, Mason and his chief engineer, Nathan Wintringer, convinced the mechanic to make a quick, temporary fix. They hammered the bulging boiler plate back into place and put a thinner patch over the leak. This quick fix took only one day instead of two or three. While the repairs were being made, the Sultana started taking on the freed prisoners. Most of these soldiers were from Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia.

Too Many People!

Captain Hatch had suggested Mason might get around 1,400 prisoners. But because of a mix-up in records and other captains suspecting bribery, the Union officer in charge, Captain George Augustus Williams, put every man from the parole camp onto the Sultana. He thought the number was less than 1,500. The Sultana was legally allowed to carry only 376 people. But when it left Vicksburg on the night of April 24, it was dangerously overcrowded. There were over 2,200 freed prisoners, 22 guards, over 120 paying passengers (mostly mothers with children), and 85 crew members. This meant more than 2,500 people were on board! Many of the prisoners were weak from being held captive and from illnesses. The men were packed into every available space. The decks even started to creak and sag in some places. Workers had to use heavy wooden beams to support them.

The Sultana spent two days traveling upriver, fighting against one of the worst spring floods ever seen on the river. In some areas, the river was three miles wide. Trees along the banks were almost completely underwater, with only their tops showing. On April 26, the Sultana stopped at Helena, Arkansas. A photographer took a picture of the incredibly crowded ship. The Sultana then arrived in Memphis, Tennessee, around 7:00 PM. The crew unloaded 120 tons of sugar. Near midnight, the Sultana left Memphis, leaving behind about 200 men. It went a short distance upriver to get more coal. Around 1:00 AM, it started heading north again.

The Explosion

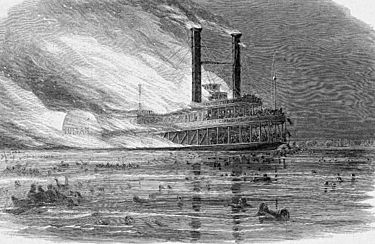

Around 2:00 AM on April 27, 1865, the Sultana was about 7 miles (11 km) north of Memphis. Suddenly, its boilers exploded. First one boiler blew up, and then two more exploded a split-second later.

The huge blast of steam shot upwards at an angle, tearing through the crowded decks above. It completely destroyed the pilothouse, where the ship was steered. Without a pilot, the Sultana became a burning ship drifting out of control. The powerful explosion threw some passengers into the water and ripped apart a large part of the ship. After a while, the two smokestacks fell over. One fell backward into the blasted hole, and the other fell forward onto the crowded upper deck. It hit the ship's bell as it crashed down. The front part of the upper deck collapsed onto the middle deck, trapping and killing many people. Luckily, strong railings around the main stairway kept the upper deck from completely crushing the middle deck. People rushed to escape the fire. The broken wood caught fire, turning the rest of the ship into a huge blaze. Survivors panicked and jumped into the cold water. But many were weak and quickly ran out of strength, clinging to each other. Whole groups of people drowned together.

Rescue Efforts

While people struggled to survive, another steamboat, the Bostona (No. 2), arrived around 2:30 AM. This was just half an hour after the explosion. It rescued many survivors. At the same time, dozens of people floated past the Memphis waterfront, calling for help. Crews on other docked steamboats and U.S. warships noticed them and immediately started rescuing survivors. Eventually, the burning remains of the Sultana drifted about 6 miles (10 km) to the west bank of the river. It sank around 9:00 AM near Mound City and present-day Marion, Arkansas. This was about seven hours after the explosion. Other ships also helped with the rescue, including the steamers Silver Spray, Jenny Lind, and Pocahontas, and the navy ships USS Essex and USS Tyler.

Passengers who survived the first explosion had to brave the icy spring waters of the Mississippi River or burn on the ship. Many died from drowning or hypothermia (getting too cold). Some survivors were found clinging to the tops of partially submerged trees along the Arkansas shore. Most of the Sultana's officers, including Captain Mason, died in the disaster.

Number of Victims

The exact number of deaths is not known for sure. However, the most recent information suggests at least 1,547 people died. Most sources believe the number was likely over 1,800, because it's thought that at least 2,500 people were on board. On May 19, 1865, less than a month after the disaster, Brigadier General William Hoffman investigated. He reported that 1,238 soldiers, passengers, and crew were lost. In 1880, the United States Congress and the War Department reported 1,259 deaths. The official count by the United States Customs Service was 1,547. The dead soldiers were first buried at the Fort Pickering cemetery in Memphis. A year later, they were moved to the Memphis National Cemetery. Three civilians who died on the Sultana are buried at Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis.

Survivors' Stories

Memphis had been taken by Union forces in 1862 and became a place for supplies and recovery. About 760 survivors were treated in local hospitals with the best medical care available. Of this group, only 31 more people died between April 28 and June 28. Newspapers reported that the people of Memphis felt great sympathy for the victims, even though Union forces occupied their city. A minstrel group called the Chicago Opera Troupe, who had traveled on the Sultana but got off in Memphis, put on a show to raise money for the victims. The crew of the gunboat Essex also raised $1,000.

In December 1885, survivors living in Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio started having yearly meetings. They formed the National Sultana Survivors' Association. Later, they decided to meet in the Toledo, Ohio, area. A group of southern survivors from Tennessee and Kentucky also started meeting in 1889. Both groups tried to meet as close to the April 27 anniversary as possible. They wrote to each other and shared the same association name.

By the mid-1920s, only a few survivors could attend the reunions. In 1929, only two men attended the southern reunion. The next year, only one man showed up. The last northern survivor, Private Jordan Barr, died on May 16, 1938, at age 93. The last overall survivor was Private Charles M. Eldridge, who died at age 96 on September 8, 1941. This was more than 76 years after the disaster.

Why It Happened

The main reason for the Sultana disaster was that the water levels in the boilers were not managed well. This problem was made worse because the ship was severely overloaded and top-heavy. As the steamboat moved up the winding river, it would tilt sharply from side to side. Its four boilers were connected. If the boat tipped, water would flow out of the highest boiler. With the fires still burning against an empty boiler, this created very hot spots. When the boat tipped the other way, water rushing back into the empty boiler would hit these hot spots. This would instantly turn into steam, causing a sudden rise in pressure. This tilting effect could have been reduced by keeping high water levels in the boilers. The official investigation found that the boilers exploded because of this tilting, low water levels, and the bad repair made a few days earlier.

A more recent investigation by Pat Jennings, an engineer from Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company (which started because of the Sultana explosion), found three main reasons for the disaster:

- The type of metal used in the boilers. It was called Charcoal Hammered No. 1. This metal tends to become weak after being heated and cooled many times. This type of metal was stopped being used for boilers after 1879.

- Using the muddy Mississippi River water to fill the boilers. The mud would settle at the bottom of the boilers or get stuck between the tubes. This created hot spots.

- The design of the boilers. The Sultana had tubular boilers with 24 horizontal five-inch tubes packed closely together. This design made it very hard to clean out the muddy sediment, which caused hot spots. Tubular boilers were no longer used on steamboats on the Lower Mississippi after two more steamboats with similar boilers exploded soon after the Sultana disaster.

Other Ideas About the Cause

In 1888, a man named William Streetor claimed that his former business partner, Robert Louden, confessed to sabotaging the Sultana. Louden was a former Confederate agent who caused damage in and around St. Louis. He had been responsible for burning another steamboat. Louden claimed he used a coal torpedo, which was a bomb disguised as a lump of coal. However, the inventor of the coal torpedo denied that one was used in the Sultana disaster. Also, the explosion happened at the top rear of the boilers, far from the fireboxes where a coal torpedo would be placed. This makes Louden's claim seem unlikely.

Two years later, another claim suggested that a former prisoner and passenger, 2nd Lt. James Worthington Barrett, caused the explosion. There is no clear reason why he would have blown up the boat, especially while he was on it.

In 1903, a newspaper reported that a Tennessee farmer sabotaged the Sultana. This farmer supposedly hollowed out a log, filled it with gunpowder, and left it on his woodpile. The Sultana supposedly took this log by mistake. However, the Sultana was a coal-burning boat, not a wood-burner, so this story is also unlikely.

A TV show called History Detectives looked into the disaster in 2014. They strongly disagreed with the sabotage theories. They focused on why the Sultana was allowed to be so overcrowded. The report blamed Quartermaster Hatch, who had a history of corruption. He kept his job because of powerful political connections. He was the younger brother of Ozias M. Hatch, an advisor and close friend of President Lincoln. After the disaster, Ozias M. Hatch refused to appear in court to give testimony. He died in 1871, having avoided justice because of his powerful friends.

No One Held Responsible

Even though it was a huge disaster, no one was ever officially held responsible. Captain Frederick Speed, a Union officer who sent the prisoners to Vicksburg, was charged with overcrowding the Sultana. He was found guilty, but the verdict was overturned. The reason was that Speed had been at the parole camp all day and had not personally put soldiers on the ship. Captain George Williams, who did put the men on board, was a regular Army officer, and the military did not want to prosecute one of their own. Captain Hatch, who had made the bribery deal with Captain Mason, quickly left the military to avoid being put on trial. Captain Mason of the Sultana, who was ultimately responsible for dangerously overloading his ship and ordering the bad repairs, died in the explosion. In the end, no one was ever held accountable for the deadliest ship disaster in United States history.

What We Remember Today

Monuments and historical markers remembering the Sultana and its victims have been put up in several places. These include Memphis, Tennessee; Muncie, Indiana; Marion, Arkansas; Vicksburg, Mississippi; Cincinnati, Ohio; Knoxville, Tennessee; Hillsdale, Michigan; and Mansfield, Ohio.

Finding the Wreck

In 1982, a local team led by attorney Jerry O. Potter found what they believed to be the wreckage of the Sultana. Blackened wooden planks and timbers were found about 32 feet (10 meters) underground in a soybean field in Arkansas. This spot is about 4 miles (6.4 km) from Memphis. The Mississippi River has changed its path many times since the disaster. This means the wreck is now on dry land, far from where the river flows today. The main river channel is now about 2 miles (3.2 km) east of where it was in 1865.

The Museum

In 2015, on the 150th anniversary of the disaster, a temporary Sultana Disaster Museum opened in Marion, Arkansas. This town is the closest to where the steamboat's remains are buried, across the Mississippi River from Memphis. The museum is temporary until enough money can be raised to build a permanent one. Inside the museum, you can see a few items from the Sultana, such as furnace plates, bricks, pieces of wood, and small metal parts. The museum also has many items from the Sultana Survivor's Association. There is also a fourteen-foot model of the boat. One entire wall is covered with the names of every soldier, crewmember, and passenger who was on the boat on April 27, 1865.

In Books, Music, and Film

Artwork

- A mural called The Sultana Departs from Vicksburg was created by artist Robert Dafford. It is part of the Vicksburg Riverfront Murals. It was dedicated on April 9, 2005.

Books

- Smith, Joe W. (2010) Sultana! This book tells the story of the disaster.

Music

- Jay Farrar of the band Son Volt wrote a song called "Sultana." It pays tribute to "the worst American disaster of the maritime." He calls the boat "the Titanic of the Mississippi" in the song.

- King's German Legion has a song called "Blues in the Water" that tells a version of the Sultana disaster.

- Josh Ritter's song "Monster Ballads" mentions the Sultana, including "Cairo" and "When the boilers blew."

- Cory Branan's song "The Wreck of the Sultana" tells the story of the disaster.

Film

- In 2018, a movie called Remember the Sultana was released. It tells the story of the disaster. It was directed by Mark and Mike Marshall and stars Ray Appleton, Mackenzie Astin, and Sean Astin.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: SS Sultana para niños

In Spanish: SS Sultana para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |