Surtout de table facts for kids

A surtout de table (pronounced "sur-TOO duh TAHB-luh") is a fancy decoration for a formal dining table. It's like a large centerpiece that often has mirrors, candle holders, and other beautiful items on top. In French, "surtout de table" means any kind of centerpiece. But in English, it usually means this special type of tray with objects placed on it.

These decorations started as simple plates or bowls. They were used to hold candlesticks and condiments like salt and pepper. Over time, a surtout de table often became a long, decorative tray. It was made from valuable or gold-plated metals. Many other objects were placed on it for display.

These trays were often made in parts. This allowed their length to be changed to fit the dining table. From the late 1700s through the 1800s, no fancy table was complete without one. Today, you can still see them in very formal dining rooms.

Contents

History of Surtouts de Table

The first surtout de table appeared in 1692. It was used at a wedding feast for Philippe II, Duke of Orléans. It was described as a "great silver gilt piece of a new invention."

At first, its main job was to hold candles and condiments. It also helped protect polished wooden tables from spills. In the early 1700s, large central salt shakers went out of style. Smaller, individual ones became popular. So, the surtout de table changed. It became the main decorative piece in the center of the table.

How Surtouts Changed Over Time

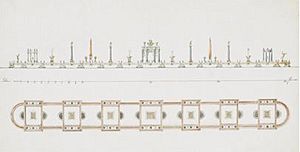

Surtouts often looked like a raised tray with a railing. This tray would hold matching candle holders, small statues, vases, and epergnes. An epergne is a fancy centerpiece with branches for holding fruit or sweets. Sometimes, the railing itself had spots for candles.

They were not always made of expensive metals. Porcelain and glass were often used. Even sculptures made from sugar could be part of them. The top of the tray was often a mirror. This showed the bottom of the objects and made the table look brighter. Other surtouts were just sculptures, sometimes very grand ones.

Themed Decorations

Sometimes, a surtout de table was made for a specific house. It would then have a theme that matched the house. For example, a hunting lodge might have one with dog figurines. A grand city palace would have the most fashionable styles of the time. Military officers often ordered ones with military subjects.

In the 1850s, themed dining table decorations were very popular. Surtouts de table showed this trend. Factories like Meissen porcelain made detailed models and figurines. These replaced the classical statues of earlier styles. They featured colorful porcelain mountains, farm scenes with animals, or even jungle themes with lifelike snakes.

Famous Surtouts de Table

Many famous surtouts de table exist. The Italian goldsmith Luigi Valadier made some notable ones. His son, Giuseppe Valadier, an architect, often designed them. These huge surtouts often looked like miniature Roman cities. They had tiny temples, columns, and arches. They were made of colored marbles and alabaster on gold bases.

Examples in England and America

Waddesdon Manor in England has a huge surtout de table. It is 6.7 meters (about 22 feet) long. It was made by Pierre-Philippe Thomire around 1818. Louis XVIII of France gave it as a gift.

George Washington ordered one from Paris in 1790. He asked for "mirrors for a table with neat and fashionable but not expensive, ornaments." He wanted the mirrors to be about ten feet long and two feet wide.

Napoleon III's Surtout

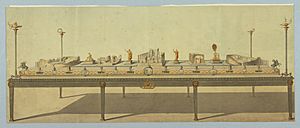

A large silver-plated bronze surtout de table was made for Napoléon III in 1852. It was called "France distributing wreaths of glory." The Parisian jeweler Charles Christofle made it. It was meant for state dinners at the Tuileries Palace.

This gilded tray has fifteen sculptures. The main figure is a winged Victory. She holds laurel leaves, giving them to two chariots. These chariots represent war and peace. Figures representing Justice, Concord, Force, and Religion sit at Victory's feet.

The surtout de table was still in the palace when it caught fire in 1871. It was pulled from the burning building, damaged but mostly whole. It has never been fixed. Today, you can see it with its smoke-blackened gold and dents at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris in Paris.

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |