The Descent from the Cross (van der Weyden) facts for kids

The Descent from the Cross (also known as Deposition of Christ) is a famous panel painting by the Flemish artist Rogier van der Weyden. He created it around 1435. Today, you can see it in the Museo del Prado in Madrid, Spain.

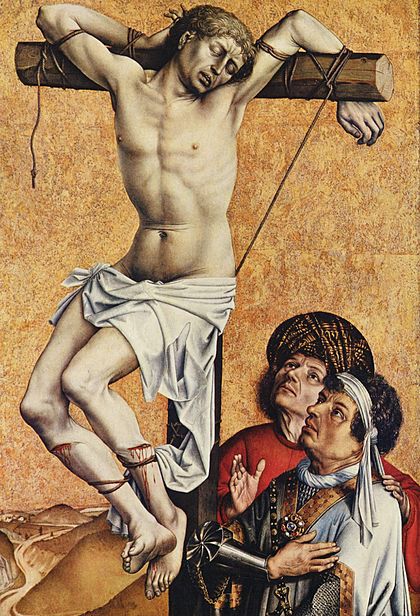

The painting shows Jesus Christ being taken down from the cross after his crucifixion. His lifeless body is held by Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus.

Experts believe the painting was made around 1435 because of its style. Also, van der Weyden became very famous and wealthy around this time, likely because of this masterpiece. He painted it early in his career, after finishing his training with Robert Campin. You can see Campin's influence in the strong, sculpted look of the figures and the bright colors, especially red, white, and blue. Van der Weyden wanted this painting to be a masterpiece that would make him known around the world.

He shaped Christ's body like a "T" or a crossbow. This was a nod to the group that ordered the painting: the archers' guild (a group of crossbowmen) in Leuven. They wanted it for their chapel.

Art historians say this painting was one of the most important artworks about Christ's crucifixion from the Netherlands. Many artists copied and used its ideas for about 200 years after it was made. People especially loved the strong emotions shown by the mourners crying over Christ's body. The way van der Weyden showed space in the painting also impressed many.

What the Painting Shows

The Bible stories about Jesus being taken down from the cross usually mention only Joseph of Arimathea preparing Christ's body for burial. The Gospel of John adds Nicodemus as an assistant. None of these early stories mention Mary, Jesus's mother, being there.

But during the Middle Ages, stories about Jesus's suffering became more detailed. People started paying more attention to Mary's role. For example, a 14th-century book called Meditationes de Vita Christi describes Mary's deep sorrow. It might have inspired artists like Rogier van der Weyden.

In the early 1400s, artists began showing Mary fainting, or "swooning," at the foot of the cross. Van der Weyden's Descent was a very important painting that showed this moment. The fainting was called spasimo by religious thinkers. Later, in the early 1500s, showing the fainting Virgin was so popular that people even asked the Pope to make a special holy day for it. But the request was turned down.

An art historian named Lorne Campbell has identified the people in the painting. From left to right, they are:

- Mary of Clopas (Mary's half-sister)

- John the Evangelist

- Mary Salome (in green, another half-sister of Mary)

- The Virgin Mary (fainting)

- The body of Jesus Christ

- Nicodemus (in red)

- A young man on a ladder (a servant)

- Joseph of Arimathea (in rich, golden robes)

- A bearded man behind Joseph (probably another servant)

- Mary Magdalene (on the right, in a dramatic pose)

Some art historians disagree about who is Joseph of Arimathea and who is Nicodemus. For example, Dirk de Vos believes the man in red supporting Christ's body is Joseph, and the man holding Christ's legs is Nicodemus. This is the opposite of Campbell's view.

How it Was Made

This painting is special because Mary faints in a way that mirrors her son's pose. She is held by two figures as she falls. This was a completely new way to show Mary's sorrow in Early Netherlandish painting.

The painting's emotional power matches the ideas in a popular book from 1418 called The Imitation of Christ. This book encouraged people to feel a personal connection to the suffering of Christ and Mary. The ideas of Denis the Carthusian also stressed Mary's importance and her faith at the moment of Christ's death. Denis believed Mary was close to death when Jesus died, and van der Weyden's painting shows this idea strongly.

The bent shape of Christ's body and arched back looks like a crossbow. This was a clever way to honor the crossbowmen's guild who ordered the painting. Some medieval thinkers even compared Christ on the cross to a stretched crossbow. In Rogier's painting, taking Christ down from the cross is like a bow relaxing after it has shot an arrow.

Art expert Dirk de Vos thinks van der Weyden wanted the painting to look like a life-sized, carved sculpture with painted figures. The corners of the painting even have carved, gilded decorations, like a real altarpiece. The figures look like they are on a stage, creating a frozen moment of intense action. Mary faints and is caught by St. John. The man on the ladder lowers Christ's body, helped by Joseph and Nicodemus. Nicodemus's movement seems to freeze Mary Magdalene in her sorrowful pose.

The painting seems to show many moments at once: the body being lowered, the removal from the cross, the mourning, and the preparation for burial. Christ's feet still look nailed together, and his arms are spread as if he is still on the cross. His body is presented for the viewer to look at closely.

Joseph of Arimathea looks across Christ's body towards a skull, which represents Adam. Joseph looks like a wealthy citizen, and his face is very detailed, almost like a portrait. His gaze connects the hands of Christ and Mary (the new Adam and Eve) with Adam's skull. This shows the idea of salvation.

De Vos also points out how complex the space in the painting is. The action happens in a very shallow space, but there are five different levels of depth: Mary in front, Christ's body, Joseph, the cross, and the assistant on the ladder. At the very back, the assistant breaks the illusion of space. One of the nails he holds sticks out in front of the painted frame!

Campbell argues that the painting's power comes not from being perfectly realistic, but from using small distortions to make the viewer feel a bit uneasy. By adding these slightly odd details, the artist makes us think more deeply about the subject.

For example, the young man at the top of the ladder holds the nails. Campbell notes that his sleeve seems caught in the wooden decoration at the top of the painting. One bloody nail is in front of the painted frame, but the other is behind it. To hide these spatial tricks, Rogier cleverly covered important meeting points. For instance, Mary's left leg is made longer so her foot and cloak cover the bottom of the cross and one leg of the ladder.

History of the Painting

The Greater Guild of Crossbowmen in Leuven ordered this painting for their chapel. You can see tiny crossbows in the side arches of the painting, showing who paid for it. Experts believe it was painted around 1435.

The painting was so famous that around 1548, it was traded for a copy made by another artist, Michael Coxcie, and an organ. The new owner was Mary of Austria, who was the sister of Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. She ruled the Habsburg Netherlands.

The painting was first kept in Mary's castle in Binche. A Spanish courtier, Vicente Alvárez, saw it in 1551 and wrote that it was "the best picture in the whole castle and even, I believe, in the whole world."

After Mary of Austria died in 1558, her nephew, Philip II, inherited the painting. He took it to Spain and placed it in his hunting lodge. In 1574, it was recorded in the inventory of the monastery palace Philip founded, El Escorial.

During the Spanish Civil War in 1936, many religious artworks were destroyed. The Spanish government worked to protect its masterpieces. The Descent from the Cross was moved from El Escorial to Valencia. In 1939, it was taken to Switzerland by train for an exhibition called "Masterpieces of the Prado" in Geneva. That September, the painting returned to the Prado Museum, where it has been ever since.

By 1992, the painting was in poor condition, with cracks and damaged paint. The Prado Museum carried out a major restoration to save it.

Its Impact

This artwork has been copied many times and had a huge impact. Even during van der Weyden's lifetime, it was seen as a very important and unique piece of art. In 1565, the first printed copy of Rogier's Descent was made.

In 1953, art historian Otto Von Simson said that "no other painting of its school has been copied or adapted so often." In a 2010 BBC documentary, Professor Susie Nash said that van der Weyden's new ideas were so powerful that other artists across Europe couldn't ignore them. She concluded that this painting might be the most important artwork of the entire 15th century.

In 2009, Google Earth worked with the Prado Museum to make twelve of its masterpieces, including Descent from the Cross, available online in super high resolution. You could see them in amazing detail!

See also

In Spanish: Descendimiento de la cruz (Rogier van der Weyden) para niños

In Spanish: Descendimiento de la cruz (Rogier van der Weyden) para niños

- List of works by Rogier van der Weyden

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |