Tollense valley battlefield facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of the Tollense Valley |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Late Bronze Age collapse | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Local Bronze Age culture, potentially associated with the Nordic Bronze Age Urnfield culture | Migrants from the east, possibly associated with the Lusatian culture or other contemporary cultures in central or eastern Europe | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| One of the oldest known battles fought in Europe | |||||||

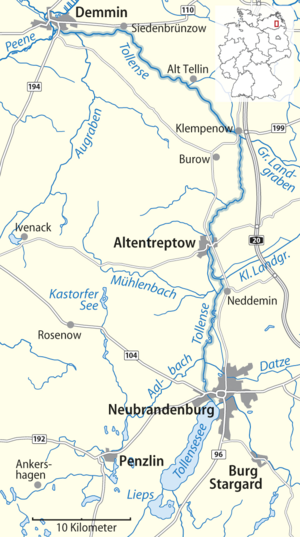

The battlefield of the Tollense valley is an amazing archaeological site from the Bronze Age. It is located in northern Germany, in the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. This special place was found in 1996. Since 2007, experts have been carefully digging there. The site stretches along the small Tollense river, near the villages of Burow and Werder.

Thousands of human bones have been found here. There is also strong proof that a huge battle took place. Experts believe that about 4,000 warriors fought in this valley around 1300 BC. This was during the 13th century BC. At that time, not many people lived in Central Europe. This battle was likely the biggest one known from the Bronze Age in this area. It is also the largest battle site from that time found anywhere in the world.

Contents

Finding the Battlefield

In 1996, a volunteer was looking around the Tollense river. The water was low, and they found a human arm bone. Inside the bone was an arrowhead made of flint. This was a very exciting discovery!

Right away, archaeologists started digging in that area. They found more human and animal bones. In the years that followed, they also found weapons. These included a club made from ash wood and a hammer-like weapon.

Since 2007, the area has been dug up very carefully. Experts from local government offices and the University of Greifswald are leading the work. Divers have searched the riverbed and banks. They have found even more human remains.

Many groups are helping with this research. They want to find out how big the site is. They are also digging through about 1 meter (3 feet) of peat, which is a type of soil. By late 2017, they had dug up 460 square meters (about 5,000 square feet). But the whole battlefield is thought to be much bigger! Volunteers use metal detectors to find objects.

Scientists have also studied the valley's geology. They figured out where the river used to flow long ago. They also used special laser scanning to map the land. Human bones found are studied at Rostock University.

The Battle Site

The battlefield is about 120 kilometers (75 miles) north of Berlin. It covers hundreds of meters on both sides of the small Tollense river. The river winds through a wide valley with marshy meadows and low hills. The river's path has not changed much over thousands of years.

During the Bronze Age, northern Europe had open landscapes. Not many people lived there, maybe only 3 to 5 people per square kilometer. There were no towns or even small villages. People likely lived in small family groups on farms. The closest large settlement to the battle site was more than 350 kilometers (217 miles) away.

In 2013, special surveys showed something interesting. There was a 120-meter (394-foot) long bridge or walkway across the valley. This structure was made of wood and stone. It was found underwater. Scientists used radiocarbon dating to check its age. Most of it was built over 500 years before the battle. But some parts might have been fixed around the time of the battle. This means the walkway was probably used for a very long time. It was a well-known landmark.

What the Findings Show

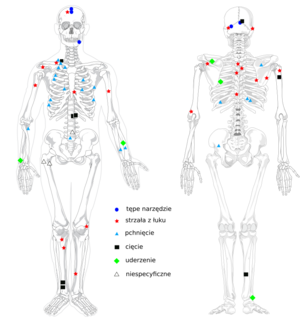

By late 2017, experts had found the remains of about 140 people. Most of them were young men, aged 20 to 40. But at least two women were also found among 14 skeletons that were tested. By March 2018, about 13,000 bone fragments had been found in total.

Scientists think that between 750 and more than 1,000 people died in the battle. The total number of fighters might have been between 3,000 and 5,000. This is based on how many people usually die in a battle. In one small area, 1,478 bones were found very close together. This might have been a pile of bodies or a last stand.

Radiocarbon dating shows the battle happened between 1300 and 1200 BC. This was during the Nordic Bronze Age. No signs of healing were found on any wounds. This suggests the battle happened very quickly, maybe in just one day. About a quarter of the skeletons show old injuries from earlier fights. This means many experienced warriors took part.

At first, people wondered if it was a cemetery or a place for human sacrifice. But the site was in a swamp, and there were no ornaments or pottery. Also, most victims were young men killed by many different weapons. So, it was clear this was not a burial site or a sacrifice. It was a battle.

Warriors used spears, clubs, swords, knives, sickles, and arrows. Over 40 skulls were found, many with battle wounds. A bronze arrowhead was even found in one skull. By late 2017, about 50 bronze arrowheads had been found. The wooden parts of the arrows also helped with dating the battle.

Some warriors rode horses into battle. Bones from at least five horses were found. The first arrowhead found in the arm bone showed an archer on foot shot a horseman. Metal weapons were found mixed with horse bones. This suggests that some fighters, perhaps leaders, had better bronze weapons and rode horses. Other soldiers had simpler weapons.

Almost no valuable items were found with the bones. This suggests that the winners probably took everything after the battle. The bodies were likely thrown into the river. The river then carried them downstream to a calmer spot. There, they were covered by turf and preserved.

In 2010, a golden spiral ring was found. In 2011, a similar one made of tin was found. These are very important because tin was needed to make bronze. These are the oldest known tin items in Germany.

Scientists have studied the bones to learn where the fighters came from. Early research suggested some came from far away. But later genetic tests showed they were all from Central Europe. They were genetically similar. Interestingly, none of these individuals could digest milk. This is surprising because the ability to digest milk is common in Europe today.

In 2016, divers found what looked like a toolkit. It had 31 bronze items, found close together. This suggests they were once in a bag or box that rotted away. The toolkit had a bronze knife, an awl, a chisel, and bronze scraps. The scrap bronze was likely used as money in the Bronze Age. Its presence suggests the owner was not from the local area. The items in the box suggest the owner came from South-Central Europe. They had traveled hundreds of miles to the battle.

Experts think a group with better weapons from the South or West wanted to cross the river. They were likely heading north or east on an important old road. This road might have been used for trading valuable goods like tin and fancy items. The battle happened during a time of big changes. Metal was becoming harder to find north of the Alps. People were also moving around a lot.

Why This Battle Matters

The main archaeologist, Detlef Jantzen, says this is the oldest proven battlefield in Europe. He also calls it one of the 50 most important archaeological sites in the world. He said, "The Tollense site has a size that no one would have thought possible for our region."

Another archaeologist, Helle Vandkilde, said, "Most people thought ancient society was peaceful... Very few talked about warfare." The Tollense site shows that large-scale violence happened in the Bronze Age.

A group of 5,000 fighters means they had to be gathered, organized, fed, and led. This would have been a huge achievement for that time. It probably means there was a strong central government. This shows that societies in Central Europe were more advanced and warlike than thought before. This was around the same time that Egypt and the Hittites signed a famous peace treaty.

The well-preserved bones and objects give us many details about the Bronze Age. They show there was a trained warrior class. They also suggest that people from all over Europe joined this bloody fight.

Archaeologist Kristian Kristiansen says the battle happened during a time of big changes. This was happening from the Mediterranean Sea to the Baltic Sea. Around this time, the Mycenean civilization in ancient Greece fell apart. The Sea Peoples who attacked the Hittites were defeated in Egypt. Not long after the Tollense Valley battle, the scattered farms in northern Europe changed. People started living in larger, heavily protected settlements.

See also

- Lusatian culture

- Urnfield culture

- Nordic Bronze Age

- Late Bronze Age collapse

- Prehistoric warfare

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |