Tomás Frías facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Tomás Frías

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17th President of Bolivia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 14 February 1874 – 4 May 1876 Acting: 31 January 1874 – 14 February 1874 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Adolfo Ballivián | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Hilarión Daza (provisional) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 28 November 1872 – 9 May 1873 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Agustín Morales | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Adolfo Ballivián | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

Tomás Frías Ametller

21 December 1805 Potosí, Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata (now Bolivia) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 10 May 1884 (aged 78) Florence, Kingdom of Italy |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | Raimunda Ballivián Guerra | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Carlos Frías Ballivián | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parents | José María Frías Alejandra Ametller |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | University of Saint Francis Xavier | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Profession | Lawyer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature |  |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

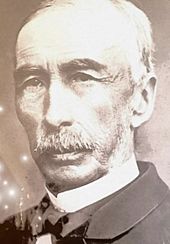

Tomás Frías Ametller (born December 21, 1805 – died May 10, 1884) was an important Bolivian lawyer and politician. He served as the 17th President of Bolivia two times. His first term was from 1872 to 1873, and his second from 1874 to 1876.

Frías started his career as a lawyer and a businessman. But he soon chose to enter the world of politics. His long political journey began in 1837. He was part of Bolivia's first group of diplomats sent to France.

He held many important jobs in the government. He was the Minister of Public Instruction and also the Minister of Finance. He worked to fix Bolivia's money problems. He was known for being honest and dedicated to his country. People even called him the "Bolivian Washington."

Contents

Tomás Frías: A Bolivian Leader

Early Life and Education

Tomás Frías was born in Potosí, Bolivia, on December 21, 1805. His family was wealthy and owned land. He grew up on their family farm in Tarapaya. His parents, José María Frías and Alejandra Ametller, made sure he received an excellent education.

He later married Raimunda Ballivián Guerra. She was the niece of another important figure, Pedro José de Guerra. They had one son named Carlos Frías Ballivián.

Becoming a Politician

Frías became a lawyer on July 13, 1826. For a while, he worked in trade, setting up a route from Potosí to Cobija. In 1828, he earned the respect of President Antonio José de Sucre. Sucre even advised him to leave business and join politics.

In 1837, President Andrés de Santa Cruz sent Frías to France. This was Bolivia's first foreign diplomatic mission. In 1843, Frías returned and became Minister of Public Instruction and Foreign Affairs. He made big changes in education in 1845. These included new rules for universities and a plan for public schooling.

Later, he was exiled from Bolivia in 1849. He returned in 1855 and became a judge in the Supreme Court. He helped create the Civil Code of 1855, which was a set of laws for the country.

Working with President Linares

In 1857, José María Linares became president. Frías was appointed Minister of Finance. In this role, he helped set up Bolivia's financial system. He was very strict about how the government spent money. He created a Central Fund for Payments to organize the national economy.

He also made sure there was a budget just for education. This money helped buy books, pay teachers, and support schools. Frías also pushed for laws to protect inventions and support businesses. He encouraged the trade of products like Quina and minerals. He worked to improve Bolivia's money system. He stayed loyal to Linares until the president was overthrown in 1861.

Challenges and Revolutions

Frías was elected to the National Assembly in 1861. He helped write the new Constitution. In 1864, Mariano Melgarejo took power, and Frías was forced to leave Bolivia again. He went to Europe.

In 1870, Frías came back to Bolivia. He wanted to live a quiet life in La Paz. But a revolution against Melgarejo started. Frías was asked to become the leader of La Paz. He supported the revolution until Melgarejo was defeated in 1871.

Frías was part of the National Assembly in 1871. He saw President Agustín Morales forcefully close the Assembly in 1872.

The President's Assassination

On November 24, 1872, there was a big celebration in La Paz. People gathered in the streets and in the main square, Plaza Murillo. A military band entered the Government Palace and stormed the room where the Assembly was meeting. They insulted and threatened the politicians. Many deputies ran away, fearing for their lives. Frías was one of the few who stayed.

The next day, some deputies demanded an apology from President Morales. They also wanted Colonel Hilarión Daza to be punished. Morales saw this as a challenge. He decided to close the Assembly himself. He entered the empty room and gave a passionate speech. He said the Assembly members were "treacherous" and "perfidious."

After his speech, Morales took on dictatorial powers. His own ministers disagreed and resigned. Morales became very agitated and attacked some of his aides. His nephew, Federico La Faye, tried to calm him down. But Morales struck him. Outraged, La Faye shot his uncle several times. President Morales died. After these dramatic events, Frías was named President by the Congress.

President of Bolivia

First Time as President (1872–1873)

After President Morales was assassinated in 1872, leaders in La Paz formed a Council of State. They chose Frías as president to keep the government running. He took office on November 28, 1872.

Frías immediately called for new elections. He did not want to stay in power longer than needed. The Constitution said he could finish Morales' term, but Frías refused. He wanted the people to choose their next leader. The National Assembly agreed to change the law. It said that the temporary president must call elections within 30 days.

One of his first actions was to sign a diplomatic agreement with Chile on December 5. This agreement aimed to solve problems from an earlier border treaty in 1866. There were disagreements about sharing guano (bird droppings used as fertilizer) and mining profits. These issues would continue to cause tension between the two countries.

A big problem during his first term was the López Gama case. A businessman named Pedro López Gama sued the government for losing guano. He won the lawsuit and was awarded a lot of money. To pay him, the government had to sell off mines. López ended up owning most of Bolivia's mining interests in the Atacama region.

The 1873 Election

The general election was set for March 1873. The main candidates were Adolfo Ballivián, Casimiro Corral, and Quintín Quevedo. Ballivián and Corral represented different political groups. Quevedo represented supporters of the old Melgarejo government.

No candidate won enough votes to become president directly. So, the National Assembly had to choose. In the end, Ballivián won with 41 votes. Both Corral and Quevedo accepted the results. Frías made sure these elections were fair and transparent. This was considered one of the cleanest elections in Bolivia's 19th century.

Second Time as President (1874–1876)

On February 14, 1874, President Ballivián died. Frías had already been acting as president since January 31 because Ballivián was very ill. It was not a surprise that Frías became president again.

Frías decided to keep the same government ministers that Ballivián had. At first, there were no challenges. But soon, people started to question his right to be president. This was especially true in La Paz and Cochabamba.

Government Challenges

Frías's first act in his second term was to reduce funding for local governments (municipalities). He said they were spending too much money. This new law also made municipalities report their expenses to the National Assembly. Many local governments, especially in La Paz and Cochabamba, protested. They said the law was against the Constitution.

Newspapers in La Paz criticized the government. This encouraged General Daza to cause trouble. To calm Daza, Frías offered him the job of Minister of War. Many people criticized this, as Daza had been plotting against the government. But Frías hoped it would prevent a civil war. This decision would have big consequences later.

The 1874 National Assembly

New elections for lawmakers were held in 1874. In La Paz and Cochabamba, most of the winners were against Frías. Despite this, Frías called the Assembly to meet. He wanted to discuss the national budget.

One big issue was a loan from the Valdeavellano company. The government owed a lot of money, and the debt was growing. On July 24, the Assembly decided to pay the entire debt.

On August 10, Frías suggested two new laws. One was about military service. He believed that a proper army would help stop rebellions. The other was about municipal reform. He wanted local governments to report their decisions to the National Assembly. The Assembly agreed with his ideas for municipalities.

The government's financial report showed a deficit in 1873. The Ministry of Public Instruction reported that they followed the Law of Free Teaching. This law promoted public education and free teaching. The Ministry of War reported that the army supported the government.

The Assembly also discussed whether Frías was legally president. Most members agreed that he was. Even some of his opponents, like General Quevedo, accepted it. But Casimiro Corral and his supporters strongly disagreed. They said Frías had given up his right to be president in 1873.

Land Law for Indigenous People

Since the time of the Spanish conquest, indigenous people had managed their communal lands. This changed when Melgarejo took these lands and gave them to others. In 1871, this was reversed, but it wasn't fully put into action.

On October 5, 1874, the Land Ex-entailment Law was passed. This law gave indigenous people the right to own the lands passed down from their ancestors. They only needed a small fee to get a legal title. This gave them clear ownership of their properties.

The Madeira-Mamoré Railway

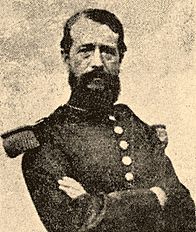

The Madeira-Mamoré Railway Company was also discussed. The company had stopped building due to a lawsuit. An engineer named Colonel George Earl Church tried to get British investors to help finish the railway.

The Assembly decided that the railway was too important to abandon. On November 25, they passed a law to support the company. It said that money from a loan would be used for construction. The government would also help the company succeed. This project aimed to connect Bolivia to the outside world through a river and rail system.

Border Treaty with Chile (1874)

The Border Conflict

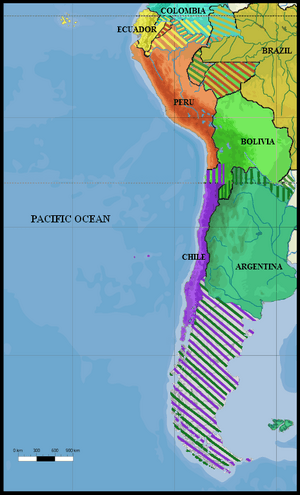

For a long time, Bolivia and Chile had argued over the Atacama desert coast. This area, called Litoral by Bolivia, was rich in resources like guano and minerals. Historically, the 25° parallel was seen as the southern border of the Peruvian Viceroyalty, which included Bolivia.

In 1842, Chile claimed ownership of guano deposits in the Atacama. A year later, Chile created its own Province of Atacama. Chilean miners even built a fort in Mejillones Bay in Bolivian territory. Bolivia destroyed the fort and removed the miners. The conflict continued for decades.

The 1866 Treaty

In 1864, the Chincha Islands War started between Spain and Peru. Bolivia was neutral at first. But Chile and Peru wanted Bolivia to join their alliance against Spain. So, in 1866, Chile negotiated with President Melgarejo. They signed the Boundary Treaty of 1866 between Chile and Bolivia.

This treaty set the border at the 24° parallel. It also said that the area between 23° and 25° parallels would be shared. Both countries would split the profits from guano and minerals there. Bolivia had to open a customs office in Mejillones.

The 1874 Treaty

The 1866 treaty was never fully put into effect. But in 1872, an agreement was reached between Bolivia and Chile. Finally, on August 6, 1874, the Boundary Treaty of 1874 was signed.

This treaty confirmed the border at the 24° parallel. It also said that profits from guano between 23° and 24° parallels would be split. Chilean companies would not pay extra taxes for 25 years. Chile also gave up its claims to Mejillones and Antofagasta. In return, Bolivia had to pay Chile.

Frías presented the treaty to the National Assembly. After much debate, it was approved on November 9. Frías knew that the part about mineral rights was unfair. So, he created a Mining Code. This treaty was important, but its violation by General Daza in 1879 led to the War of the Pacific.

Quevedo's Rebellion (1874–1875)

Army Mutiny

On November 30, 1874, a group of soldiers in the Bolivian Army rebelled. They marched towards Cochabamba. The city authorities tried to stop them but had to retreat. General Quevedo negotiated with the soldiers and got their leader released. The soldiers demanded their unpaid wages.

On December 1, they were paid. But the next day, they rebelled again. They declared General Daza as president. Quevedo calmed them down again. He declared himself the military chief of Cochabamba. Frías sent Daza and another group of soldiers to deal with the situation. By December 21, the rebellious soldiers had scattered.

Rebellion Spreads to La Paz

News of the rebellion in Cochabamba reached La Paz. On December 23, another group of soldiers mutinied. They took over the city. General Quevedo, who had lost the 1873 election, wanted to take power. He entered La Paz on January 5, 1875.

Casimiro Corral, another opponent of Frías, joined Quevedo. They published a revolutionary message on January 9. Quevedo gathered an army of 1,200 men. President Frías personally led his troops to stop the rebellion.

Battle of Chacoma

On January 18, Frías's forces attacked Quevedo's army at Chacoma. Frías's soldiers advanced bravely. Even the 70-year-old President Frías participated in the battle. He refused to leave the fight, even when his son warned him.

After 25 minutes of intense fighting, Frías's forces broke through the enemy lines. Quevedo's army was completely defeated and scattered. Frías's side had very few casualties. Quevedo's troops suffered many losses, and many fled.

Continued Rebellions

On January 16, another rebellion broke out in Cobija. They also proclaimed Quevedo as leader. But when they heard about Quevedo's defeat at Chacoma, they surrendered. By February 3, the rebellion in the Litoral region was over.

In La Paz, Quevedo's allies also tried to start a new uprising. On March 20, revolutionaries gathered and marched on the main plaza. They fought fiercely for eight hours against government forces defending the Palace. The rebels tried to burn the palace. The eighth attempt caused a massive fire.

The third floor of the Government Palace was engulfed in flames. Later, government troops arrived and defeated the rebels. The next day, 130 bodies were found. The burning of the Government Palace gave it its current name, "Palacio Quemado" (Burnt Palace). Frías continued to put down other revolts, finally ending Quevedo's rebellion.

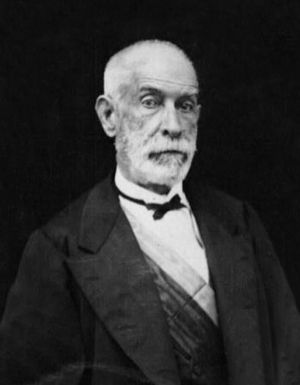

Daza's Coup (1876)

As new elections approached, General Hilarión Daza was a strong candidate. Daza expected Frías to support him. But Frías refused to support any candidate. Daza was also angry because he had been replaced as Minister of War.

Daza controlled the army, and his support grew. There were rumors of a plot against the government. Frías sent a message to army bases to ensure their loyalty. Daza intercepted this message and was furious. Despite this, Daza promised his loyalty to Frías, calling him his "father."

On May 4, 1876, Jorge Oblitas, another candidate, met with Daza. He agreed to support a coup against the government. The revolution began. Frías and his ministers decided to stay in the Government Palace and defend it.

Soldiers surrounded the Palace. Frías tried to leave but was stopped. He told the soldiers he was the president. Some soldiers cheered for him, but then louder cheers came for General Daza. Soldiers blocked Frías with their bayonets. Frías and his ministers were arrested.

The next day, May 5, most ministers were released. But Daniel Calvo and Mariano Baptista remained imprisoned. Frías was moved to a convent. After Daza took power, Frías was allowed to leave the country. He went to Arequipa and tried to plan new revolts. But Daza had too much power. Frías accepted defeat and fled to Europe.

Exile and Death

When the War of the Pacific started, Frías offered to help Bolivia. He was made a diplomat in France. While in Paris, he even asked for a pay cut to help fund the war effort.

After his work was done, he retired to Florence, Italy. He died there on May 10, 1884. His body was brought back to Bolivia and buried in his hometown of Potosí. The Tomás Frías Province and Tomás Frías Autonomous University are named after him to honor his memory.

See also

In Spanish: Tomás Frías Ametller para niños

In Spanish: Tomás Frías Ametller para niños

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |