Tosa Mitsuoki facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Tosa Mitsuoki

|

|

|---|---|

| 土佐光起 | |

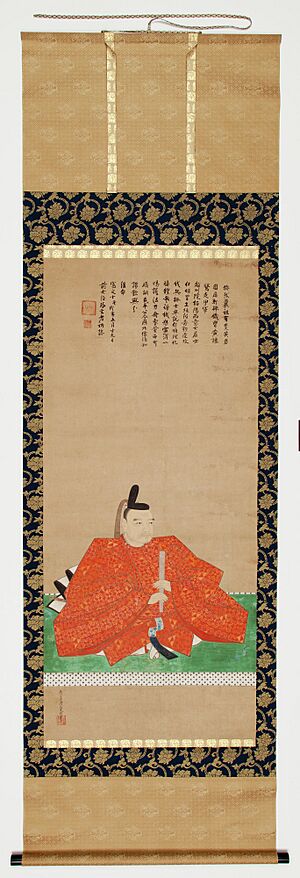

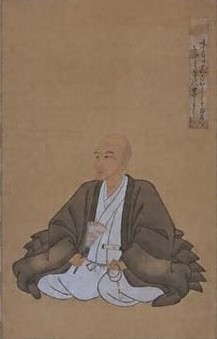

Painting of Tosa Mitsuoki by Tosa Mitsunari in the Kyoto National Museum

|

|

| edokoro azukari, Head Imperial Court Painter | |

| In office 1654–1681 |

|

| Preceded by | Tosa Mitsunori |

| Succeeded by | Tosa Mitsunari |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 21 November 1617 Sakai, Izumi |

| Died | 14 November 1691 (aged 73) Kyoto, Japan |

| Children |

|

| Parent |

|

Tosa Mitsuoki (土佐 光起, November 21, 1617 – November 14, 1691) was a famous Japanese painter.

He became the leader of the Tosa school of painting after his father, Tosa Mitsunori. Mitsuoki moved the Tosa school back to Kyoto after it had been in Sakai for about 50 years. In Sakai, his father painted for regular townsfolk. The school was not as well-known then as it had been under an earlier leader, Mitsunobu. In 1634, Mitsuoki and his father moved to Kyoto. Mitsuoki wanted to make the Tosa school famous again and get back its important role at the Kyoto court. Around 1654, he became the official court painter, a job called edokoro azukari. This role had traditionally belonged to the Tosa family but was held by the Kanō school for many years.

Contents

Bringing the Tosa School Back

In 1634, Emperor Go-Mizunoo asked Mitsuoki to move from Sakai to Kyoto. Mitsuoki's father started painting special ceremonial fans for the court. In 1654, Mitsuoki took over from his father, Tosa Mitsunori. He was given the important title of edokoro azukari, which meant "head of the Imperial court painting office." The Tosa school became very successful during the Edo period (1600 to 1868). The Kyoto court's important people once again loved Tosa school artworks.

Mitsuoki's painting style was a bit different from older Tosa traditions. He was influenced by Chinese painting and even the Kanō school. This made his art popular with more people at the imperial court. Mitsuoki's son, Tosa Mitsunari, and other family members followed him as court painters. Many of them used the same style as Mitsuoki. This meant their art looked very similar to his. Because they didn't change their style much, people slowly lost interest in the family's work. The school eventually faded out in the 1800s. In 1690, Mitsuoki helped write a book called Honchou gahou daiden. This book shared many Tosa painting techniques that had been passed down by word of mouth.

How Art Was Made in Workshops

Art schools in historical Japan were very different from modern ones. They were more like family businesses or workshops. Skills were often kept secret and passed down from a master to a student, usually by talking. Not many written records exist about these old art workshops. What we do have are things like personal diaries, letters, and notes on artworks.

In these workshops, tasks were divided based on how skilled someone was. The head of the workshop was like a manager. They worked with the rich people who ordered paintings. They also made sure the art was kept safe, fixed old paintings, and decided how much art was worth.

After Mitsuoki's Time

Later, in the 1700s, the Tosa style became less popular. It was overshadowed by the growing Kanō school. However, in the 1800s, two artists named Tanaka Totsugen and Reizei Tamechika brought the Tosa style back. They focused on copying Mitsuoki's work. Their art showed the Japanese spirit of Yamato-e (traditional Japanese painting). They often painted historical figures. The most successful artists after Mitsuoki created their own styles. But they still kept the Tosa tradition of using strong colors and showing natural beauty.

Mitsuoki's Painting Style

Mitsuoki made the Yamato-e (大和絵) style of classical Japanese painting popular again. Yamato-e started by copying early Chinese paintings. Later, it was changed to fit Japanese culture. By the Muromachi period, Yamato-e became known as the Tosa school's style. It helped Japanese artists show their work was different from Chinese paintings.

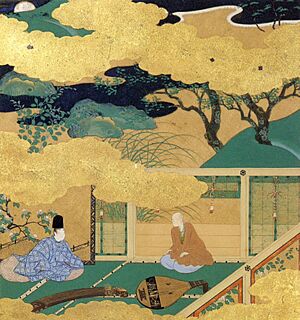

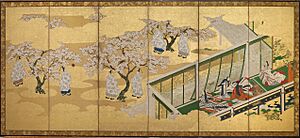

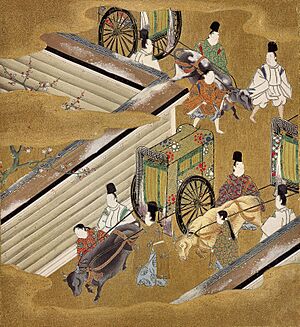

Yamato-e paintings often told stories using pictures and sometimes text. Tosa style, especially with Mitsuoki, focused on nature. They painted plants, famous places (meisho-e), the four seasons (shiki-e), and birds and flowers (kachō-e). Many of these ideas came from Chinese art.

Mitsuoki's paintings were often made on:

- Wall scrolls (kakemono)

- Handscrolls (emakimono) that you would read from right to left with a story

- Sliding doors (fusuma)

- Folding screens (byobu) with up to six panels

Mitsuoki's style used deep colors and brush techniques similar to Chinese court paintings. He used sketch-like lines and was great at adding decorative details. His art was decorative, refined, and very precise. He was known for his beautiful and delicate lines, especially in his bird and landscape paintings. He used bright colors, sometimes with gold, to create a beautiful harmony. He became one of the most famous Japanese painters of bird-and-flower scenes, especially his detailed pictures of quails. His flower paintings were elegant and gentle. Mitsuoki's older style was serious, but his new art gained a gentle and calm feeling. The Emperor, nobles, and rich families collected his artworks.

It is easy to see the drastic shift of Mitsuoki's artistic practice when put in comparison with his father, Mitsunori, and fellow contemporary Kano-he artist, Kano Tan'yu. Here we are better able to see how Mitsuoki uses void between defining figures, with tonal washes of color only being broken by equally formless instances of gold leaf hinting at an obscuring fog. Here, the fog's nature acts similar to the curtain and delineates the dreamscape of The Tale of Genjifrom the viewer's reality much more effectively than the frame-like mist of Mitsunori's interpretation. Mitsuoki's space is voluminous, much like that of Kano Tan'yu's Phoenixes by Paulownia Trees. The sparseness of objects grounding Mitsuoki's space invites the viewer to wonder among the ambiguous vastness of the space; where as Mitsunori's work does not cause this sharing of reality and treats the viewer as if they are watching through a window. Mitsuoki's clouds feel as though they could be dispersed and reveal hidden figures.

| Tosa Mitsunori | Tosa Mitsuoki | Kano Tan'yu |

|---|---|---|

Famous Works

| Title | Technique | Format | Dimensions(cm) | Signature | Year | Current location | image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quail and Millet | Ink and Color on Silk | Hanging scroll | 124.14 × 69.85 × 2.54 cm | Tosa sakon shogen Mitsuoki | 17th Century | Dallas Museum of Art | |

| Ono no Komachi | Ink and Color on Silk | Hanging scroll | 73.3 x 31.3 | Tosa sakon shogen Mitsuoki | 17 Century | ||

| Ishiyama-dera engi emaki | 4 parts | 1655-81 | Ishiyama-dera | ||||

| Song of Twelve months | Ink and color on silk | 2 part scroll | Volume 1 29.0x665.0 Volume 2 29.0x663.5 |

1664-68 | Tokyo National Museum | ||

| Egrets and Cotton Roses | Ink and Color | Hanging scroll | 118.5 × 56.3 | Tosa sakon shogen Mitsuoki hitsu | 17th Century | Metropolitan Museum of Art | |

| Portrait of Hojo Ujinaga | Ink and Color on paper | Hanging scroll | 127.2x56.4 | 1670-81 | Detroit Institute of Arts | ||

| Toyotomi Hideyoshi portrait | Ink and color | Hanging scroll | 75.2x31.5 | Tosa sakon shogen Mitsuoki hitsu | 17th Century | Taigan Historical Museum, Sun Collection | |

| Sakaorimiya Renga | Scroll | Tosa sakon shogen Mitsuoki hitsu | 17th Century | Yamanashi Prefectural Museum | |||

| Genji Monogatari Folding Screen | Ink and Color | 6 panel folding screen | 100.7x286.0 (panel) | 17th Century | Tokyo National Museum | ||

| Mushrooms Skewered on Bamboo Twig | Ink and Color on Silk | Hanging scroll | Tosa sakon shogen Mitsuoki hitsu | 17th Century | British Museum | ||

| Yashima Uji River Hejian screen | Ink and Color | 6 panel folding screen | 155.1x365.4 (panel) | 17th Century | Tokyo National Museum | ||

| Album of Thirty six Immortal Poets | Ink and Color | booklet | 17.5x15.4 (panel) | 17th Century | The University Art Museum - Tokyo University of the Arts | ||

| Flowering Cherry and Autumn Maples with Poem Slips | Ink and color, Gold and Silver | 2 x 6 Panel Folding screens | 144x286 (panel) | Tosa sakon shogen Mitsuoki hitsu | 1654-81 | Art Institute of Chicago |

About the Tosa School

The Tosa school claimed it was founded in the 800s and was not influenced by Chinese art. However, its style does show some Chinese influence. Besides religious art, the Tosa school focused on art for the Kyoto Court. They painted things like quails, peacocks, cherry blossoms, and Daimyō (feudal lords) in fancy clothes. Over time, their style became very precise and detailed.

As years passed, the Tosa painters lost some of their fame to artists from the later Kanō school. The Kanō school studied a wider range of subjects. Tosa school paintings were known for their elegant and precise designs. The Kanō school, on the other hand, was known for its powerful and free designs.

Tosa School and Kanō School: Similarities

If you look closely at old works from both the Tosa and Kanō schools, you can see they had similar drawing styles. Both schools were supported by the Japanese courts around the same time. They both specialized in Yamato-e and ukiyo-e paintings.

However, they served different purposes in the Edo court. Kanō painters usually made large screens and hanging scrolls for public areas. These were places where men gathered in the homes of shōguns and daimyōs. Tosa artists' courtly style was often used for decorating private rooms. These rooms were used by women and children. Their art was also found in albums and scrolls given at weddings. There was a clear artistic connection between the two schools. The daughter of Tosa Mitsunobu even married Kanō Motonobu.

After the Tosa school became less popular around the 1500s, the Kanō school became more dominant. Tosa artists often worked under Kanō artists, sometimes helping them with final sketches. The Tosa school's lack of new ideas made it less popular with the general public.

Art in Edo During Mitsuoki's Life

After Tokugawa Ieyasu started the city of Edo, Japan entered a long period of isolation. The third shōgun, or military ruler, closed Japan off from most of the world. Only very limited trade happened at the port of Nagasaki. This isolation policy began around 1637. During this time, Edo became a very important center for politics, money, and art in Japan. It grew into one of the world's largest cities. Its art showed the spirit of this new, lively city.

Edo also saw a new middle class emerge. People in each social class were allowed to develop their own styles and culture. This was true as long as it didn't challenge the higher-ranked military families. Before this time, art was usually only for the upper class and the wealthy courts. Artists were not pressured by the Kyoto courts to create work only for the rich. In this "floating world" of Edo, artists could choose their own style and even their own audience. New types of art appeared that interested merchants and the middle class. Art was no longer just for the elite; anyone who could afford it could enjoy it. The Shōgun of Edo and the Kyoto court continued to support the Tosa school. They also supported other important schools like the Kanō school.

|

See also

In Spanish: Tosa Mitsuoki para niños

In Spanish: Tosa Mitsuoki para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |