Trust (social science) facts for kids

Trust is when you are willing to depend on someone (the trustor) even though you don't fully control what they do. You believe they will act in a way that helps you. There are two main kinds of trust:

- General trust: This is trusting many people you don't know well.

- Specific trust: This is trusting someone in a certain situation or because of a special relationship.

When you trust someone, you're not completely sure what will happen. You form ideas about how the other person (the trustee) will act, based on who they are, the situation, and how you interact. There's always a risk that things might not go as you hope, or that you could be harmed if the trustee doesn't do what you expect.

Experts in social studies are always learning more about trust. In fields like sociology (the study of society) and psychology (the study of the mind), trust shows how much you believe someone is honest, fair, or kind. The word "confidence" is often used for believing in someone's skills. If someone makes a mistake because they weren't skilled enough, it might be easier to forgive than if they were dishonest. In economics, trust often means how reliable someone is in business deals. In all these cases, trust helps us make decisions quickly without having to think about every single possibility.

Contents

Trust in Society

Sociology teaches that trust is a big part of how our society works. Other ideas often linked with trust include control, confidence, risk, meaning, and power. Trust naturally happens in relationships between people and groups. Sociologists study where trust fits in social systems. Interest in trust has grown a lot since the 1980s, especially as society has changed and become more modern.

Society needs trust because we often face new and unknown situations. Without trust, we would have to think about every possible outcome, which would make it impossible to make decisions. Trust helps us choose one path, hoping it will lead to the best results. Once we decide to trust, we stop worrying about negative things that could happen. This helps make social life simpler and allows people to work together.

Sociology looks at trust in two ways:

- Big picture view: How trust works in large social systems, like a whole country.

- Small picture view: How trust works between individual people.

Sociology also understands that when the future is uncertain, people become dependent on each other. Trust is one way to handle this dependency, and it's often better than trying to control someone. Trust is especially helpful when the person you trust is much more powerful than you, but you still need to support them.

New computer technologies have changed society and how we think about trust. Research shows that people have started to trust technology itself. This trust comes from believing technology is helpful, reliable, and works well, similar to how we trust people for being kind, honest, and skilled.

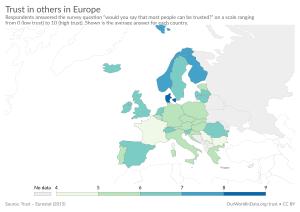

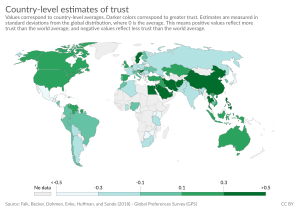

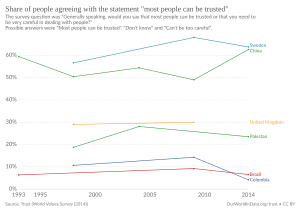

Societies with High and Low Trust

Different Kinds of Trust

There are four main types of social trust:

- Generalized trust: This is trusting strangers, which is very important in modern society where we interact with many people we don't know.

- Out-group trust: This is trusting people who are part of a different group than yours, like people from another country or ethnic group.

- In-group trust: This is trusting people who are part of your own group.

- Trust in neighbors: This is about the relationships between people who live near each other.

How Different Groups Affect Trust

Many studies have looked at how having different ethnic groups in an area affects social trust. Researchers have found a small but steady link: more ethnic diversity can slightly reduce social trust. This effect is strongest for trust in neighbors, in-group trust, and generalized trust. It doesn't seem to affect trust in out-groups much. However, the impact is small, so it's not a huge problem.

Trust in Psychology

In psychology, trust means believing that the person you trust will do what you expect. According to psychologist Erik Erikson, learning basic trust is the first big step in a child's development, happening in the first two years of life. If a child learns to trust, they feel safe and hopeful. If they don't, they might feel insecure and have trouble forming close relationships later. A person's natural tendency to trust others is a part of their personality and can greatly affect how happy they are. Trust helps people have better relationships, and happy people are good at building strong connections.

Trust is key to influencing others: it's easier to convince someone who trusts you. People are increasingly using the idea of trust to predict if others will accept certain behaviors, if they will trust organizations (like government groups), or even objects like machines. Again, believing in honesty, skill, and shared values is very important.

Psychologists often study three forms of trust:

- Trust: Being willing to be open with someone, even if there's a risk.

- Trustworthiness: The qualities or actions of a person that make others believe in them.

- Trust propensity: Your general tendency to trust others. This can change over time due to major life events.

Once trust is broken, especially by a clear violation of these factors, it's very hard to get back. It's much easier to break trust than to build it.

Recent research has explored how trust affects social interactions. For example, studies show that people tend to trust others more if their faces look similar. In games where people had to trust each other with money, those with similar facial features were trusted more. This suggests that facial resemblance and trust can have a big impact on relationships.

Situations that test trust can help people understand or change the level of trust in their relationships. These "strain-test" situations challenge partners to act in the best interest of the other person or the relationship, even if it means giving up something for themselves. These situations happen in daily life or can be created to see how much trust exists.

In relationships with low trust, people don't believe their partner truly cares about them or the relationship. They tend to focus on the negative actions of their partner and downplay any positive ones. This makes them think their partner isn't interested, and positive actions are met with doubt, leading to more negative outcomes.

People who have experienced a difficult childhood, like abuse, might find it hard to trust others in the future. Also, trust can be affected by parents getting divorced. However, children of divorce don't necessarily trust their mothers, partners, friends, or others less than children from intact families. The impact of divorce seems mostly limited to trust in the father.

It's important to know that we can trust non-human things too, like animals, scientific processes, and even social robots. Trust helps us live with domestic animals. Trust in science is linked to trusting new inventions like biotechnology. When it comes to trusting social machines, people are more likely to trust smart machines that look human-like, especially if they have female features, are focused on tasks (not just talking), and act morally good. Generally, people might trust robots more than humans because they think machines are less biased, more accurate, and more reliable.

Humans naturally tend to trust and judge how trustworthy others are. This can be seen in how our brains work. Some studies even suggest that trust can be changed by certain chemicals in the brain, like oxytocin.

Trust and Group Identity

The social identity approach explains that we trust strangers based on what we think about their group or if they are part of our "in-group." People generally think well of strangers, but they expect better treatment from people in their own group. This expectation makes them more likely to trust someone from their own group than someone from an "out-group." This only works if both people know they are part of the same group.

Many studies have looked at this. For example, in games where money is shared, people often trust members of their own group more, even if that group isn't seen as better by others. This happens even when there are no personal clues about the other person. However, if only the person receiving the money knows the group membership, trust depends more on general group stereotypes. For instance, someone might trust a nursing student more than a psychology student if nursing is seen as a more positive group, even if the psychology student is from their own university. Trust in out-group strangers can increase if personal details about them are shared.

Trust in Philosophy

Many philosophers have written about different kinds of trust, but most agree that trust between people is the basic form. For an action to show trust, it must not go against what the person trusting expects. Some philosophers say trust is a kind of reliance, but it's more than just that. Diego Gambetta believed that trust comes from a basic belief that others generally have good intentions.

However, philosophers like Annette Baier disagree, saying that trust can be betrayed, while reliance can only be disappointed. For example, you rely on your clock to tell the time, but you don't feel betrayed if it breaks. You just feel disappointed. You also aren't trusting someone if you're suspicious of them; that's actually a sign of distrust. When trust is broken, that feeling of betrayal is usually justified. So, trust is different from reliance because the person trusting accepts the risk of being betrayed.

Karen Jones suggested that trust has an emotional side, a feeling of optimism that the person being trusted will do the right thing. This is called emotional trust. But sometimes, we trust others without this optimistic feeling, hoping that just knowing they are being trusted will make them act favorably. This is called therapeutic trust. In these cases, the feeling of betrayal when trust is broken is usually warranted.

Some definitions of trust say it's just a belief or a confident expectation, which removes the idea of risk. For example, if your friend is always late, you might confidently expect them to be late for dinner. This isn't about what you wish for, but about what you know from past behavior. So, there's no risk or betrayal, just an accurate prediction. This is called predictive trust, and if it's wrong, you might feel disappointed, but not betrayed.

Trust in Economics

In economics, trust helps explain why people act differently than they would if they were only trying to get the most for themselves. Trust can explain why real-world outcomes are different from what simple economic models predict. This applies to both individuals and whole societies.

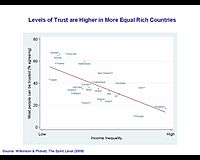

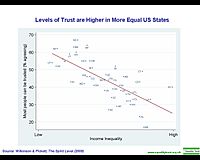

Trust is very important to economists. Imagine buying a car: if you don't trust the seller not to sell you a bad car, you won't buy it, even if the car is good. Trust acts like a "lubricant" for the economy, making it cheaper and easier for people to do business together. It helps new kinds of cooperation happen and generally boosts business, jobs, and wealth. This idea has led to a lot of research into trust as a form of social capital (the value of social networks). It's believed that more social trust leads to better economic development. While the idea of "high-trust" and "low-trust" societies might be too simple, it's widely accepted that social trust helps the economy, and a lack of trust slows down economic growth. Low trust can limit job growth, wages, and profits, reducing the overall well-being of society.

Economic models suggest that the perfect amount of trust for a smart economic agent to show is equal to how trustworthy the other person is. This leads to an efficient market. Trusting too little means missing out on economic chances, while trusting too much can make you vulnerable and possibly exploited. Economists also try to measure trust, often in money terms. They look at how much an increase in trust leads to more profit or lower costs, to see its economic value.

Economists often use "trust games" in labs to measure trust. These games are set up so that if players only act selfishly, no one benefits much. But if they cooperate, everyone can gain. A classic trust game involves an investor and a broker. The investor can give some money to the broker, and the broker can return some of the gains. If both act selfishly, the investor would never invest, and the broker would never get anything to return. So, any money that flows in this game is entirely due to trust. These games can be played once or many times, with the same or different players, to study general trust or trust in specific relationships. Many versions of this game exist.

Other popular games include the "gift-exchange game" and games based on the Prisoner's Dilemma, which show how trust and cooperation can be rational choices.

The rise of e-commerce (online shopping) has brought new challenges and increased the importance of trust. Online, buyers and sellers don't meet in person, so technology has had to help build trust. Websites can influence buyers to trust sellers, even if the seller isn't actually trustworthy. Systems based on reputation (like customer reviews) have improved how we judge trustworthiness online, leading to much interest in different models of reputation.

Trust in Management and Organizations

In business and organization studies, trust is seen as something that can be managed and influenced by people within a company. Experts have looked at how trust develops at both individual and company levels. They suggest that company structures affect how much individuals trust, and at the same time, individual trust shows up in how the company is structured. Trust is also key to a company culture that encourages knowledge sharing. When employees feel safe and comfortable sharing their knowledge and work, it helps the whole organization. A well-organized workplace can also build trust, making employees feel more comfortable and perform better.

Scholars in management have also studied how contracts influence trust and how trust works with formal rules. Alongside the great interest in trust, many researchers have also highlighted the importance of distrust, seeing it as a related but separate idea.

Since the mid-1990s, much research on trust in organizations has focused on two main ideas. The first looks at two types of trust:

- Cognition-based trust: This is based on logical thinking, like trusting a car repair shop because you know they have good mechanics.

- Affect-based trust: This is based on emotions, like trusting a car repair shop because you have a long-standing relationship with the owner.

The second idea looks at the factors that make someone trustworthy (like their skill, kindness, and honesty) and separates these from trust itself. Together, these ideas help predict how different kinds of trust form in organizations based on how trustworthy people are seen to be.

Trust in Systems

In computer or other systems, a "trusted component" has certain qualities that another part of the system can rely on. If System A trusts System B, and System B fails in those qualities, System A might not work correctly. It's important that the qualities System A trusts in System B actually match System B's real abilities. If they don't, the whole system could be at risk. So, the trustworthiness of a component is how well it performs its functions and other important qualities, based on how it's built and its environment.

Other Kinds of Trust

In politics, trust is often linked to how much people believe their government or political leaders can make a difference.

See Also

In Spanish: Confianza para niños

In Spanish: Confianza para niños

- Anticipation

- Attachment theory

- Credulity

- Gullibility

- Intimacy

- Leap of faith

- Misplaced trust

- Personal boundaries

- Position of trust

- Source criticism

- Swift trust theory

- Trust metric

- Trusted system

- Trust in computing

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |