Erik Erikson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Erik Erikson

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Erik Salomonsen

15 June 1902 |

| Died | 12 May 1994 (aged 91) Harwich, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Citizenship |

|

|

Notable work

|

|

| Spouse(s) |

Joan Serson

(m. 1930) |

| Children | 4, including Kai T. Erikson |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | |

| Notable students | Richard Sennett |

| Influences | |

| Influenced |

|

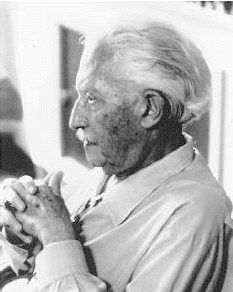

Erik Homburger Erikson (born Erik Salomonsen; 15 June 1902 – 12 May 1994) was a famous German-American developmental psychologist and psychoanalyst. He is best known for his important theory on how people develop throughout their lives. He also created the well-known phrase "identity crisis".

Even though Erikson never went to university, he taught as a professor at top schools. These included Harvard, the University of California, Berkeley, and Yale. In 2002, a survey ranked him as the 12th most important psychologist of the 20th century.

Contents

Erik Erikson's Early Life

Erikson's mother, Karla Abrahamsen, came from a well-known Jewish family in Copenhagen, Denmark. Erik was born in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, on June 15, 1902. His biological father was a non-Jewish Dane, whose identity was never fully known.

After Erik was born, his mother became a nurse. She moved to Karlsruhe. In 1905, she married Theodor Homburger, a Jewish children's doctor. In 1908, Erik's name was changed to Erik Homburger. In 1911, his stepfather officially adopted him. Erik's parents told him that Theodor was his real father. They only told him the truth when he was older. This made Erik feel bitter for the rest of his life.

Finding His Identity

Erikson's own journey to understand his identity was very important to him. It also became a main part of his work. When he was older, he wrote about feeling "identity confusion" as a teenager in Europe. He said it was "on the borderline between neurosis and adolescent psychosis."

His daughter later wrote that Erikson truly found his "psychoanalytic identity" when he changed his last name. He replaced his stepfather's name, Homburger, with a new name he made up: Erikson. He made this change when he started working at Yale. His family accepted the "Erikson" name when they became American citizens. His children even joked that they wouldn't be called "Hamburger" anymore!

Erik was a tall boy with blond hair and blue eyes. He was raised in the Jewish faith. Because of his mixed background, he faced teasing from both Jewish and non-Jewish children. At his temple school, kids teased him for looking "Nordic." At his regular school, he was teased for being Jewish.

At high school, he liked art, history, and languages. But he wasn't very interested in school overall. He graduated without special honors. His stepfather wanted him to go to medical school. Instead, Erik went to art school in Munich.

Becoming an Artist and Teacher

Erik felt unsure about what he wanted to do with his life. He dropped out of art school. For a long time, he traveled around Germany and Italy as a wandering artist. He often sold his sketches to people he met. Eventually, Erik realized he wouldn't become a full-time artist. He went back to Karlsruhe and became an art teacher.

While teaching, Erik was hired by a wealthy woman to sketch and tutor her children. He was very good with kids. Soon, other families close to Anna Freud and Sigmund Freud hired him too. During this time, which lasted until he was 25, he kept thinking about his father and his own ethnic, religious, and national identity.

Erikson's Psychoanalytic Training

When Erikson was 25, his friend Peter Blos invited him to Vienna. He was asked to teach art at a special school for children. These children's parents were getting psychoanalysis from Anna Freud, Sigmund Freud's daughter.

Anna Freud noticed how good Erikson was with children. She encouraged him to study psychoanalysis at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute. There, famous analysts like August Aichhorn and Heinz Hartmann helped him with his studies. He focused on child analysis and had his own training analysis with Anna Freud. In 1933, he received his diploma from the Institute. This, along with a Montessori diploma, were the only official degrees he earned for his life's work.

Life in the United States

In 1930, Erikson married Joan Mowat Serson, a Canadian dancer and artist. They met at a costume ball. During their marriage, Erikson became a Christian.

In 1933, Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany. Freud's books were burned in Berlin. The Nazi threat grew in Austria. So, Erikson and his family left Vienna. They moved to Copenhagen, but Erikson couldn't get Danish citizenship. So, they moved to the United States.

In the U.S., Erikson became the first child psychoanalyst in Boston. He worked at several places, including Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School. He quickly became known as a great clinician. In 1936, Erikson left Harvard and joined Yale University. He worked at the Institute of Social Relations and taught at the medical school.

Studying Culture and Development

Erikson became more interested in areas beyond just psychoanalysis. He explored how psychology and anthropology were connected. He met important anthropologists like Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict. Erikson said his ideas about how people think came from his studies of different societies and cultures.

In 1938, he left Yale to study the Sioux tribe on their reservation in South Dakota. After that, he went to California to study the Yurok tribe. Erikson noticed differences in how children developed in the Sioux and Yurok tribes. This experience started his lifelong passion. He wanted to show how important childhood events are and how society affects them.

In 1939, the Eriksons moved to California. Erik was invited to join a study on child development at the University of California, Berkeley. He also opened a private practice for child psychoanalysis in San Francisco. While in California, he made his second study of American Indian children. He joined anthropologist Alfred Kroeber to study the Yurok people in Northern California.

In 1950, Erikson published his most famous book, Childhood and Society. After this, he left the University of California. This was because California required professors to sign loyalty oaths, which he disagreed with. From 1951 to 1960, he worked and taught at the Austen Riggs Center. This was a well-known mental health facility in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. He worked with young people who were struggling emotionally. During this time, he also taught as a visiting professor at the University of Pittsburgh.

He returned to Harvard in the 1960s as a professor. He stayed there until he retired in 1970. In 1973, he received the Jefferson Lecture, a top honor in the humanities in the U.S.

Erikson's Theories on Development

Erikson is known as one of the creators of ego psychology. This idea focuses on the "ego" (your sense of self) as more than just serving your basic desires. Erikson agreed with Freud's ideas. But he focused more on how a person grows and develops their self-identity. He believed that the environment a child lives in is very important for their growth and sense of who they are.

Erikson won a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award for his book Gandhi's Truth (1969). This book looked at how his theory applied to later stages of life.

Erikson's theory of development includes different "psychosocial crises." Each crisis builds on the ones before it. How a person deals with each conflict can have good or bad effects on their development. But a negative outcome can be worked on and improved later in life.

For example, "ego identity versus role confusion" is a key idea. Ego identity means having a strong sense of who you are as an individual. Erikson said it's "the awareness of the fact that there is a self-sameness and continuity to the ego's synthesizing methods and a continuity of one's meaning for others." Role confusion, on the other hand, means not being able to see yourself as a useful part of society. This can happen during the teenage years when you're trying to figure out your future job or role.

Erikson's Eight Stages of Life

Erikson's theory describes eight stages of development that people go through from birth to old age. Each stage has a challenge, and successfully dealing with it helps you gain a "virtue" or strength.

- Hope: Basic trust vs. basic mistrust

Age: 0–1½ years (infancy) This is the most important stage. It's about whether a baby learns to trust the world or not. It depends on how well their caregivers provide steady and loving care. If successful, the baby develops a sense of trust, which helps them form their identity. If not, they might feel fear and think the world is unpredictable.

- Will: Autonomy vs. shame

Age: 1½–3 years (early childhood) Children start to discover their independence. They want to do things "all by themselves," like toilet training. Parents should let them explore and try tasks. If they are discouraged or shamed for mistakes, they might doubt their own abilities. Success leads to a sense of self-control without losing self-esteem.

- Purpose: Initiative vs. guilt

Age: 3–5 years (preschool) Children start making their own games and decisions. They ask many questions to learn about the world. If they are allowed to make choices, they gain confidence. If they are criticized or made to feel like a burden, they might feel guilty and become followers. Success helps them develop a sense of purpose.

- Competence: Industry vs. inferiority

Age: 5–12 years (school age) Children compare themselves to others. Friends and teachers become very important. They try to prove their skills in things society values. Encouragement helps them feel capable and confident. If they are held back or feel they can't achieve, they might feel inferior. Success leads to a sense of competence.

- Fidelity: Identity vs. role confusion

Age: 12–18 years (adolescence) This is when teenagers ask "Who am I?" and "Where am I going?" They explore their beliefs, goals, and values. If parents allow this exploration, teens find their own identity. If pushed to conform, they might feel confused about who they are. Teens also think about future jobs and relationships. Success leads to fidelity, which is the ability to commit to others and accept differences.

- Love: Intimacy vs. isolation

Age: 18–40 years (young adulthood) This stage is about forming close relationships with others. Dating, marriage, family, and friendships become very important. If people can form loving relationships, they experience love and feel safe. If they struggle to form lasting connections, they might feel isolated and alone. Success leads to the virtue of love.

- Care: Generativity vs. stagnation

Age: 40–65 years (middle adulthood) People are often settled in their careers and raising children. This stage is about contributing to society. This can be through parenting, teaching, mentoring, or community work. People who feel they are making a difference experience generativity. If they are unhappy with their life choices, they might feel regret and uselessness. Success leads to the virtue of care.

- Wisdom: Ego integrity vs. despair

Age: 65+ years (late adulthood) This is the final stage. People look back on their lives. They must accept their life fully—the good and the bad. If they feel good about their life, they achieve ego integrity and wisdom. Wisdom means having a calm understanding of life, even in the face of death. If they have many regrets, they might feel despair, depression, and hopelessness.

For information on the Ninth Stage, you can read more at Erikson's stages of psychosocial development § Ninth Stage.

Erikson believed that for each stage, you need to understand both sides of the challenge. For example, you need to understand both "trust" and "mistrust" to truly develop "hope." This way, the best strength for that stage can appear.

Erikson and Religion

Erikson also studied how religion affects people's lives. He believed that religious traditions can connect with a child's basic sense of trust or mistrust.

He wrote two famous books that looked at the lives of important religious figures: Young Man Luther, about Martin Luther, and Gandhi’s Truth, about Mohandas K. Gandhi. He won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award for Gandhi's Truth. These books showed how childhood, family, culture, and even political events shape a person's identity. Erikson showed how these influential people found strength and made big changes in their time. He called them "Homo Religiosus"—people for whom the challenge of integrity vs. despair was a lifelong journey. They became gifted innovators whose own personal growth led to new ideas for their time.

Personal Life

Erikson married Joan Mowat Serson in 1930. She was a Canadian dancer and artist. They stayed together until his death.

The Eriksons had four children: Kai T. Erikson, Jon Erikson, Sue Erikson Bloland, and Neil Erikson. His oldest son, Kai T. Erikson, became an American sociologist. His daughter, Sue, who is a psychotherapist, said her father often felt "personal inadequacy" throughout his life. He believed that by working with his wife, he could gain the recognition he needed to feel good enough.

Erikson passed away on May 12, 1994, in Harwich, Massachusetts. He is buried in the First Congregational Church Cemetery in Harwich.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |