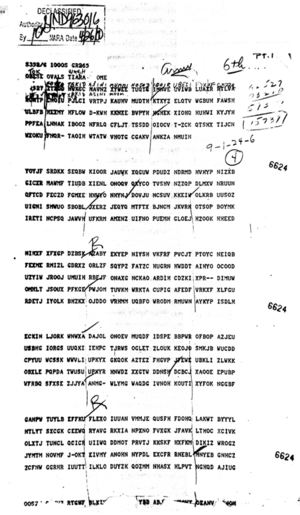

Type B Cipher Machine facts for kids

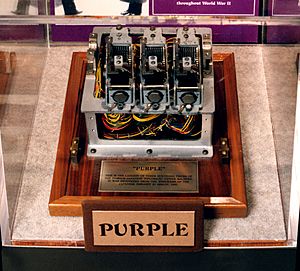

The "System 97 Typewriter for European Characters" (九七式欧文印字機), also known as the "Type B Cipher Machine", was a secret coding machine used by the Japanese Foreign Office. The United States gave it the codename Purple. It was used from February 1939 until the end of World War II.

This machine was an electronic device that used special switches to encrypt (scramble) very important diplomatic messages. All messages were written using the 26 letters of the English alphabet, which was common for sending telegrams. If the Japanese wanted to send messages in their own language, they had to change it into English letters first.

The machine split the 26 letters into two groups: one with six letters and one with twenty letters. The six-letter group was scrambled in a simpler way. The twenty-letter group was scrambled much more thoroughly using three different stages of mixing.

The Purple machine replaced an older Japanese coding machine called the Type A, or Red machine. American code-breakers, from the U.S. Army Signals Intelligence Service (SIS), already knew about the two-group system from the Red machine. This helped them start breaking the six-letter part of the Purple code early on. The twenty-letter part was much harder. But in September 1940, they had a big breakthrough. The Army code-breakers were able to build their own machine that worked just like the Japanese Purple machine, even though they had never seen the original!

The Japanese also used similar switch-based systems called Coral and Jade. These machines did not split their alphabets into two groups. The secret information the Americans got from breaking these codes was called Magic.

Contents

How Japanese Code Machines Were Made

Early Machines

During World War II, the Imperial Japanese Navy and the Imperial Japanese Army did not work together on making code machines. The Navy thought the Purple machine was so strong that no one could break it. They didn't try to make it better. This idea came from a mathematician named Teiji Takagi, who wasn't an expert in breaking codes. The Navy gave the Red and Purple machines to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. No one in Japan realized how weak these machines actually were.

Just before the war ended, the Army warned the Navy about a weakness in the Purple code, but the Navy didn't do anything about it. The Army made their own code machines, similar to the German Enigma machine. These were called 92-shiki injiki, 97-shiki injiki, and 1-shiki 1-go injiki. The Army thought their machines were less secure than the Navy's Purple design, so they used them less often.

The Red Machine

In 1922, American code-breakers secretly read Japanese diplomatic messages during talks for the Washington Naval Treaty. When this became public, Japan felt a lot of pressure to make their codes better. The Japanese Navy had already planned to create their first code machine for the London Naval Treaty talks. Navy Captain Risaburo Ito oversaw this work.

The machine was developed by the Japanese Navy Institute of Technology. In 1928, the main designer Kazuo Tanabe and Navy Commander Genichiro Kakimoto created a test version of the Red machine. This test machine was used by the Japanese Navy and Foreign Ministry during the London Naval Treaty talks in 1930.

The test machine was finished as the "Type 91 Typewriter" in 1931. In the Japanese calendar, 1931 was year 2591, so it was named "91-shiki."

The "91-shiki injiki" model for Roman letters was used by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as the "Type A Cipher Machine." American code-breakers called it "Red."

The Red machine often had problems unless its parts were cleaned every day. It encrypted vowels (A, E, I, O, U, Y) and consonants separately. This was probably done to save money on telegrams, but it made the code much weaker. The Navy also used a version of the "91-shiki injiki" for Japanese Kana letters at their bases and on ships.

The Purple Machine

In 1937, Japan finished its next generation machine, the "Type 97 Typewriter." The Ministry of Foreign Affairs used this as the "Type B Cipher Machine," which the U.S. called Purple.

The main designer of Purple was Kazuo Tanabe. His engineers were Masaji Yamamoto and Eikichi Suzuki. Eikichi Suzuki suggested using a stepping switch instead of the older, more problematic switches.

The Purple machine was definitely more secure than Red. However, the Navy didn't realize that the Red machine had already been broken. The Purple machine kept a weakness from the Red machine: six letters of the alphabet were still encrypted separately. The difference was that the group of six letters changed every nine days. In the Red machine, these were always the vowels (A, E, I, O, U, Y). Because of this, the U.S. Army SIS was able to break the code for the six letters before they could break the code for the other 20 letters.

How the Purple Machine Worked

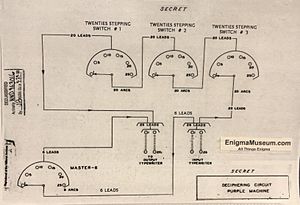

The Type B Cipher Machine had several parts. The U.S. Army figured out it had electric typewriters at both ends, similar to the Red machine. For encrypting messages, the Type B worked like this:

- An input typewriter where you typed the message.

- A plugboard that mixed up the letters from the keyboard and separated them into a group of 6 letters and a group of 20 letters.

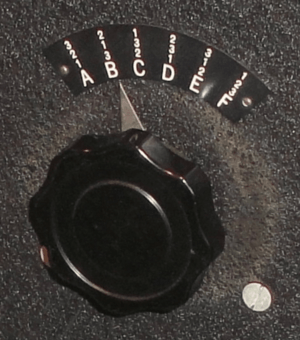

- A stepping switch with 6 layers that chose one of 25 ways to scramble the letters in the six-letter group.

- Three stages of stepping switches (called I, II, and III), connected one after another. Each stage was like a 20-layer switch that chose one of 25 ways to scramble the letters in the twenty-letter group. The Japanese used three 7-layer stepping switches to build each stage. The U.S. SIS used four 6-layer switches per stage in their first copy machine.

- An output plugboard that reversed the first mixing and sent the letters to the output typewriter for printing.

- The output typewriter, which typed the scrambled message.

To decrypt (unscramble) a message, the process was reversed. The second typewriter became the input, and the twenty-letter stages worked in the opposite order.

Stepping Switches Explained

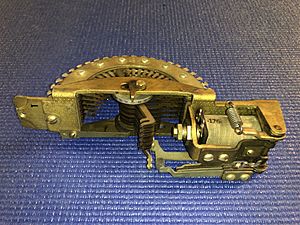

A stepping switch is a mechanical device with many layers. It was commonly used in telephone systems at the time. Each layer has 25 electrical contacts arranged in a half-circle. These contacts stay still and are called the stator. A moving arm, called a wiper, on a rotor connects to one contact at a time. The rotors on each layer are attached to a single rod that moves from one contact to the next when an electromagnet is pulsed. This allows the connections to cycle through all 25 contacts.

To encrypt the twenty-letter group, a 20-layer stepping switch was needed in each of the three stages. Both the Japanese machine and the early American copy used several smaller stepping switches, like those found in telephone offices, to build each stage. The American copy used four 6-layer switches to create one 20-layer switch. The four switches in each stage moved together. A piece of a Japanese Type 97 machine, which is the largest known piece, has three 7-layer stepping switches. The U.S. Army made an improved copy in 1944 that had all the layers for each stage on a single rod.

How the Switches Stepped

The stages could work in both directions. Signals went through each stage one way for encryption and the other way for decryption. Unlike the German Enigma machine, the order of the stages was fixed, and there was no reflector. However, the way the switches moved could be changed.

The six-letter switches moved one position for each character encrypted or decrypted. The movements of the switches in the twenty-letter stages were more complex. The three stages were set to move fast, medium, or slow. There were six possible ways to set this, and the choice was decided by a number at the beginning of each message called the message indicator. The U.S. improved copy machine had a six-position switch for this. The message indicator also set the starting positions of the twenty-letter switches. This indicator was different for each message or part of a message. The last part of the code, the plugboard arrangement, was changed daily.

The twenty-letter switch movement was partly controlled by the six-letter switch. Only one of the three twenty-letter switches moved for each character. The fast switch moved for each character, unless the six-letter switch was in its 25th position. Then the medium switch moved, unless it was also in its 25th position, in which case the slow switch moved.

Breaking the Purple Code

The SIS learned in 1938 that a new diplomatic code was coming, thanks to decoded messages. Purple messages started appearing in February 1939.

The Purple machine had several weaknesses, some in its design and others in how it was used. By looking at how often letters appeared (frequency analysis), code-breakers could often see that 6 of the 26 letters in the coded message stood out from the other 20. This suggested that Purple used a similar system to the Type A machine, splitting the letters into two groups. The weaker encryption for the "sixes" was easier to analyze. The six-letter code turned out to be a polyalphabetic cipher with 25 fixed scrambled alphabets, used one after another. The only difference between messages with different indicators was the starting position in the list of alphabets. The SIS team figured out these 25 scrambles by April 10, 1939.

Knowing the original text of 6 out of 26 letters, even if scattered, sometimes helped guess parts of the rest of the message. This was especially true when the writing style was very specific. Some diplomatic messages included the exact text of letters from the U.S. government to the Japanese government. The English text of these messages could usually be found. Also, some diplomatic offices didn't have the Purple machine, especially when it was new. Sometimes, the same message was sent in both Purple and the older Red code, which the SIS had already broken. All these things gave the Americans "cribs" (known parts of the message) to help attack the twenty-letter code.

William F. Friedman led the group of code-breakers working on the Purple system starting in August 1939. Even with the cribs, progress was hard. The scrambles used in the twenty-letter code were "brilliantly" chosen, according to Friedman. It became clear that they wouldn't find repeating patterns just by waiting for enough messages with the same indicator, because the plugboard alphabets changed daily. The code-breakers found a way to change messages sent on different days with the same indicator so they would look like they were sent on the same day. This gave them enough messages with identical settings (6 messages with indicator 59173) to find a pattern that would reveal how the twenty-letter code worked.

On September 20, 1940, Genevieve Grotjan Feinstein found evidence of cycles in the twenty-letter code. This was a huge breakthrough, and it soon allowed them to build a copy machine. Two other messages using indicator 59173 were decrypted by September 27. This was the same day that the Tripartite Pact between Nazi Germany, Italy, and Japan was announced. There was still a lot of work to do to figure out the meaning of the other 119 possible indicators. By October 1940, one-third of the indicator settings had been figured out. From time to time, the Japanese tried new ways to make the Purple system stronger. But they often described these changes in messages sent using the older system, which gave the Americans a warning.

The idea for building the Purple copy machine came from Larry Clark. Further understanding of how Purple keys worked was made by Lt Francis A. Raven. After the first breakthrough, Raven found that the Japanese had divided the month into three 10-day periods. Within each period, they used the keys from the first day with small, predictable changes.

The Japanese believed Purple was unbreakable throughout the war, and even for some time after the war. This was true even though the Germans had told them otherwise. In April 1941, Hans Thomsen, a German diplomat in Washington, D.C., sent a message to Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German foreign minister. He told Ribbentrop that "an absolutely reliable source" had informed him that the Americans had broken the Japanese diplomatic code (Purple). That source was likely Konstantin Umansky, the Soviet ambassador to the U.S., who had figured it out from talks with U.S. Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles. The message was sent to the Japanese, but they continued to use the code.

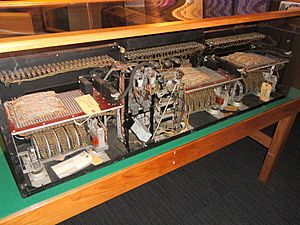

American Copies of Purple

The SIS built its first machine that could decrypt Purple messages in late 1940. A second Purple copy was built for the U.S. Navy. A third was sent to England in January 1941. That Purple copy went with a team of four American code experts, two from the Army and two from the Navy. They received information about British successes against German codes in exchange. This machine was later sent to Singapore, and then to India. A fourth Purple copy was sent to the Philippines, and a fifth was kept by the SIS. A sixth, originally for Hawaii, was sent to England for use there. The Purple messages proved important in Europe because of the detailed reports on German plans sent by the Japanese ambassador in Berlin using that code.

Finding Japanese Machines

The United States found parts of a Purple machine at the Japanese Embassy in Germany after Germany's defeat in 1945. They discovered that the Japanese had used a stepping switch almost identical to the one Leo Rosen of SIS had chosen when building a copy machine in Washington in 1939 and 1940. The stepping switch was a standard part used in large numbers in automatic telephone exchanges in countries like America, Britain, Canada, Germany, and Japan. The U.S. used four 6-level switches in each stage of its Purple copies, while the Japanese used three 7-level switches. Both worked the same way for the twenty-letter code.

It seems that all other Purple machines at Japanese embassies and consulates around the world (like in Axis countries, Washington, London, Moscow, and neutral countries) and in Japan itself were destroyed by the Japanese. American troops in Japan searched for any remaining units from 1945 to 1952. A complete Jade cipher machine, which worked on similar ideas but without the six- and twenty-letter separation, was captured and is now on display at the NSA's National Cryptologic Museum.

How Allied Code-Breaking Helped

The Purple machine was first used by Japan in June 1938. But American and British code-breakers had already broken some of its messages well before the attack on Pearl Harbor. U.S. code-breakers decrypted and translated Japan's 14-part message to its Washington embassy to break off talks with the United States. They did this at 1 p.m., Washington time, on December 7, 1941, before the Japanese Embassy in Washington had even delivered it. Problems with decrypting and typing at the embassy, plus not knowing how important it was to deliver it on time, were major reasons why the "Nomura Note" was delivered late.

During World War II, the Japanese ambassador to Nazi Germany, General Hiroshi Oshima, knew a lot about German military plans. His reports went to Tokyo in Purple-coded radio messages. One message said that Hitler told him on June 3, 1941, that "war with Russia cannot be avoided." In July and August 1942, Oshima visited the Eastern Front. In 1944, he toured the Atlantic Wall defenses against invasion along the coasts of France and Belgium. On September 4, Hitler told him that Germany would attack in the West, probably in November.

Since the Allies were reading these messages, they got valuable information about German military preparations against the coming invasion of Western Europe. General George Marshall said Oshima was "our main basis of information regarding Hitler's intentions in Europe."

The decrypted Purple messages and other Japanese messages were discussed in angry hearings in Congress after World War II. These hearings tried to figure out who, if anyone, was to blame for allowing the attack on Pearl Harbor to happen. It was during these hearings that the Japanese first learned that the Purple cipher machine had indeed been broken.

The Soviets also managed to break the Purple system in late 1941. Along with reports from Richard Sorge, they learned that Japan was not going to attack the Soviet Union. Instead, Japan's targets were southward, towards Southeast Asia and American and British interests there. This allowed Stalin to move many troops from the Far East to Moscow in time to help stop the German push to Moscow in December.

See also

In Spanish: PURPLE para niños

In Spanish: PURPLE para niños