Richard Sorge facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Richard Sorge

|

|

|---|---|

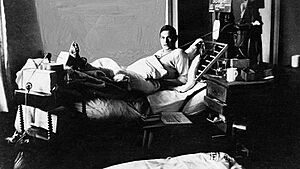

Sorge in 1940

|

|

| Nickname(s) | Ramsay |

| Born | 4 October 1895 Baku, Baku Governorate, Caucasus Viceroyalty, Russian Empire (now Baku, Azerbaijan) |

| Died | 7 November 1944 (aged 49) Sugamo Prison, Tokyo, Empire of Japan |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

Imperial German Army Soviet Army (GRU) |

| Years of service | Germany 1914–1916, USSR 1920–1941 |

| Awards | Hero of the Soviet Union Order of Lenin Iron Cross, II class (for World War I campaign) |

| Spouse(s) | Christiane Gerlach (1921–1929), Ekaterina Alexandrovna (1929(?)–1943) |

| Relations | Gustav Wilhelm Richard Sorge (father) Friedrich Sorge (great-uncle) |

Richard Sorge (Russian: Рихард Густавович Зорге, romanized: Rikhard Gustavovich Sorge; 4 October 1895 – 7 November 1944) was a German journalist and Soviet military intelligence officer. He worked secretly as a German journalist before and during World War II. He was active in both Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan. His secret code name was "Ramsay" (Рамза́й).

Sorge is famous for his work in Japan in 1940 and 1941. He shared important information about Adolf Hitler's plan to attack the Soviet Union. In mid-September 1941, he told the Soviets that Japan would not attack them soon. About a month later, Sorge was arrested in Japan for spying. He was later executed in November 1944. The Soviet leader, Stalin, chose not to help him.

After his death, Sorge was given the title of Hero of the Soviet Union in 1964.

Contents

Richard Sorge's Early Life

Richard Sorge was born on October 4, 1895. His birthplace was Sabunchi, a town near Baku, which is now in Azerbaijan. He was the youngest of nine children. His father was a German mining engineer, and his mother was Russian. In 1898, his family moved back to Germany. Sorge later said that being born in the southern Caucasus and moving to Berlin at a young age made his life different.

Sorge started school in Berlin when he was six. He described his father's political views as "nationalist and imperialist," which he also believed when he was young. Sorge thought Friedrich Adolf Sorge, a friend of Karl Marx, was his grandfather. However, he was actually Sorge's great-uncle.

In October 1914, Sorge joined the Imperial German Army. This was soon after First World War began. He was 18 years old. He fought on the Western Front and was wounded in 1915. After recovering, Sorge was sent to the Eastern Front. He was promoted to corporal. In April 1917, he was seriously wounded again. For his bravery, Sorge received the Iron Cross, Second Class. He was then discharged from the army because of his injuries.

After the war, Sorge changed his political views. He had started as a nationalist but became disappointed by the war. He called the conflict "meaningless." He then became interested in left-wing politics. While recovering, he read books by Marx and Engels. He became a communist, partly influenced by a nurse's father. He studied philosophy and economics at various universities. He later joined the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). He worked as an activist for the party. His political views led to him losing a teaching job and coal mining work.

Becoming a Soviet Spy

Richard Sorge was recruited to work as a spy for Soviet intelligence. He used his job as a journalist as a cover. He was sent to different European countries to see if communist revolutions might happen.

From 1920 to 1922, Sorge lived in Solingen, Germany. He was joined by Christiane Gerlach, who later became his wife in May 1921. In 1922, he moved to Frankfurt. There, he gathered information about businesses. In 1923, he attended a conference. Sorge continued his journalism and helped with a new Marxist research center.

In 1924, Sorge met Osip Piatnitsky, a high-ranking official. Piatnitsky recruited Sorge to work for the Communist International. That year, Sorge and Christiane moved to Moscow. He officially joined the International Liaison Department, which also gathered intelligence. Sorge's dedication to his work led to his divorce. In 1925, he became a Soviet citizen. He worked as an assistant and secretary in Moscow.

After some years, Sorge was invited to join the Red Army's Fourth Department in 1929. This department later became the GRU, which is military intelligence. He stayed with the GRU for the rest of his life.

In 1929, Sorge went to the United Kingdom. He studied the labor movement and the country's political situation. He was told to stay undercover and out of politics. In November 1929, Sorge was sent to Germany. He was told to join the Nazi Party and avoid left-wing activists. He got a job with an agricultural newspaper as his cover.

Spying in China (1930)

In 1930, Sorge was sent to Shanghai, China. His cover was being an editor for a German news service and the Frankfurter Zeitung newspaper. He met other Soviet agents there. He also met American journalist Agnes Smedley, who introduced him to Hotsumi Ozaki, a Japanese journalist. Ozaki later became one of Sorge's recruits.

Soon after arriving in China, Sorge sent important information. He reported on plans by Chiang Kai-shek's government to attack the Chinese Communist Party. This information came from German military advisors.

As a journalist, Sorge became an expert on Chinese agriculture. He traveled around the country and met members of the Chinese Communist Party. In January 1932, Sorge reported on fighting between Chinese and Japanese troops in Shanghai. In December, he was called back to Moscow. His work in Shanghai was seen as very successful. He had avoided being caught and had grown the Soviet spy network.

Setting Up in Japan (1933)

In May 1933, the GRU decided Sorge should create a spy network in Japan. His code name was "Ramsay." He first went to Berlin to get new newspaper assignments in Japan. In September 1931, the Japanese Kwantung Army had taken over Manchuria in China. This gave Japan a new border with the Soviet Union. At the time, some Japanese generals wanted to invade the Soviet Far East. Moscow knew this because they had broken Japanese army codes. Until the mid-1930s, Japan was seen as the main threat by Moscow, not Germany.

Sorge joined the Nazi Party in Germany. He read Nazi propaganda, including Adolf Hitler's Mein Kampf. He was very good at pretending to be a strong Nazi journalist. When he left Germany, even Joseph Goebbels, a top Nazi official, attended his farewell dinner. Sorge traveled to Japan through the United States, arriving in Yokohama on September 6, 1933.

In Japan, Sorge became the correspondent for the Frankfurter Zeitung. This was a very important German newspaper. His status as a Nazi journalist who seemed to dislike the Soviet Union was a perfect cover for his spying. His mission in Japan was harder than in China. The Soviets had little intelligence there, so Sorge had to build a network from scratch. He was also watched much more closely. His GRU bosses told him to "study very carefully whether or not Japan was planning to attack the USSR." After his arrest, Sorge told his captors that this was the most important part of his mission.

Sorge was told not to contact the secret Japanese Communist Party or the Soviet embassy in Tokyo. His spy network in Japan included Max Clausen, a radio operator, and Hotsumi Ozaki. It also included Branko Vukelić, a journalist, and Miyagi Yotoku, a Japanese journalist. Max Clausen's wife, Anna, sometimes carried messages. Clausen also ran a successful business as a cover. Ozaki was a Japanese man from an important family. He believed Japan's political system was old-fashioned and wanted Japan to become a socialist state.

Between 1933 and 1934, Sorge built his network of informants. His agents had connections with important politicians. They got information about Japanese foreign policy. His agent Ozaki became close to Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe. Ozaki copied secret documents for Sorge.

Sorge was welcomed at the German embassy because he seemed to be a strong Nazi. German diplomats, including Ambassador Herbert von Dirksen, relied on Sorge for information about Japanese politics. Sorge spoke Japanese well, which helped his reputation. He was interested in Asian history and culture. Sorge became friends with General Eugen Ott, the German military attaché. Ott's wife, Helma, copied reports about the Japanese Army and gave them to Sorge. Sorge then sent them to Moscow. Helma Ott thought Sorge was working for the Nazi Party.

In October 1934, Ott and Sorge visited the puppet state of "Manchukuo" (a Japanese colony). Sorge wrote the report describing Manchukuo, which Ott submitted to Berlin under his own name. Sorge soon became one of Ott's main sources of information. This led to a close friendship. In 1935, Sorge sent a document from Ozaki to Moscow. It showed that Japan was not planning to attack the Soviet Union in 1936. Sorge correctly predicted that Japan would invade China in July 1937. He also said there was no danger of a Japanese invasion of Siberia.

On February 26, 1936, a military coup attempt happened in Tokyo. Several officials were killed. The German embassy was confused. They asked Sorge for help. Using notes from Ozaki, Sorge explained that the coup was by younger officers. They were upset about poverty in the countryside. Sorge's report was used by Ambassador Dirksen to explain the coup to Berlin.

Sorge's spying for the Soviets in Japan was probably safer than being in Moscow. He did not obey Josef Stalin's orders to return to the Soviet Union in 1937. He knew he might be arrested because he was German. Many of his GRU handlers were executed during Stalin's purges. In 1938, Ott became the ambassador to Japan. Ott trusted Sorge completely. He allowed Sorge to freely access the embassy. Sorge even helped draft messages that Ott sent to Berlin. Ott trusted Sorge so much that he sent him to carry secret messages to other German offices. Sorge noted that embassy staff often asked him for his opinion.

On May 13, 1938, Sorge crashed his motorcycle in Tokyo and was badly hurt. He was carrying secret notes from Ozaki. If the police had found them, his cover would have been blown. But a member of his spy ring got to the hospital and removed the documents before the police arrived. In 1938, Sorge reported that the Battle of Lake Khasan was caused by overzealous officers. He said Tokyo had no plans for a general war against the Soviet Union.

Sorge's reports that Japan did not plan to invade Siberia were not always believed in Moscow. On September 1, 1939, Moscow criticized Sorge. They said he had not provided enough information about Japan's military plans against the Soviet Union.

Wartime Intelligence (1941)

Sorge gave Soviet intelligence information about the Anti-Comintern Pact and the German-Japanese Pact. In 1941, his contacts at the embassy told him about Operation Barbarossa. This was the upcoming Axis invasion of the Soviet Union. On May 30, 1941, Sorge reported to Moscow that the German attack would start in late June. On June 20, 1941, Sorge reported that war between Germany and the USSR was "inevitable." He also said the Japanese General Staff was discussing their position. Moscow received these reports, but Stalin and other Soviet leaders did not believe Sorge's warnings.

It has been said that Sorge gave the exact date of "Barbarossa." However, historian Gordon Prange concluded that the closest Sorge came was June 20, 1941. Sorge himself never claimed to know the exact date (June 22). The date of June 20 was given to Sorge by a German officer at the embassy. Despite knowing an invasion was coming, Sorge was still shocked on June 22, 1941, when he learned of Operation Barbarossa.

In late June 1941, Sorge told Moscow that Ozaki had learned the Japanese cabinet decided to occupy southern French Indochina (now Vietnam). He also reported that invading the Soviet Union was an option, but Prime Minister Konoe had chosen neutrality for the moment. On July 2, 1941, an Imperial Conference decided against war with the Soviet Union. They ordered preparations for a possible war against the United States and the British Empire. Ozaki reported this to Sorge. On September 14, 1941, Sorge reported to Moscow that the possibility of Japan attacking had "disappeared."

Sorge told the Red Army that Japan would not attack the Soviet Union unless:

- Moscow had been captured.

- The Kwantung Army was three times larger than Soviet forces in the Far East.

- A civil war had started in Siberia.

This information allowed the Soviet Union to move army divisions from the Far East. These divisions were then used in the Battle of Moscow. This battle was the German Army's first major defeat. Many believe Sorge's information was one of the most important pieces of military intelligence in World War II. However, Sorge was not the only source. Soviet codebreakers had also learned that Japan would not attack the Soviet Union in 1941.

Arrest and Trial

As the war continued, Sorge was in more danger. His radio messages were encrypted with special codes that were impossible to break. However, the increasing number of mysterious messages made the Japanese suspect a spy ring was active. Sorge was also becoming more suspected in Berlin. By 1941, the Nazis had a German official in Tokyo, Josef Albert Meisinger, monitor Sorge. Sorge managed to become friends with Meisinger. Meisinger reported to Berlin that the friendship between Ambassador Ott and Sorge was so close that Sorge's reports were often signed by the Ambassador.

The Kempeitai, the Japanese secret police, intercepted many messages. They began to close in on the German Soviet agent. Sorge's second-to-last message to Moscow in October 1941 said, "The Soviet Far East can be considered safe from Japanese attack." In his last message, Sorge asked to be sent back to Germany. He wanted to help the Soviet war effort by providing more information about Germany. Ozaki was arrested on October 14, 1941, and questioned immediately.

Sorge was arrested shortly after, on October 18, 1941, in Tokyo. The next day, Ambassador Ott was told Sorge was arrested for "espionage." Ott was surprised and thought it was "Japanese espionage hysteria." He believed Sorge might have passed information to the German embassy. A few months later, Japanese authorities announced Sorge was a Soviet agent.

He was held in Sugamo Prison. The Japanese first thought Sorge was a German spy because of his Nazi Party membership. But the German intelligence agency denied it. Sorge eventually confessed. However, the Soviet Union denied he was a Soviet agent. The Japanese offered to trade Sorge for one of their own spies three times. But the Soviet Union refused every time, saying they did not know Sorge.

Sorge's wife, Katya Maximova, was arrested in September 1942. She was accused of being a "German spy" because she was married to Sorge. She died in 1943. Hanako Ishii, a Japanese woman Sorge loved, was the only person who tried to visit him in prison. Sorge made a deal with the Kempeitai. He said he would tell them everything if they spared Ishii and the wives of the other spies. Ishii was never arrested. Sorge told his captors that his success in gaining the German embassy's trust was key to his spying. He said Moscow considered it "extremely amazing."

Death and Legacy

Richard Sorge was executed on November 7, 1944, in Sugamo Prison. Hotsumi Ozaki was executed earlier that same day. Sorge was buried in a mass grave for prison inmates.

Sorge's Japanese partner, Hanako Ishii (1911 – July 1, 2000), later found his body. She had him cremated. A memorial stone at the site has an epitaph in Japanese. It reads: "Here lies a hero who sacrificed his life fighting against war and for world peace."

The Soviet Union did not officially recognize Sorge until 1964.

Honors and Recognition

In the 1950s, Sorge's reputation in West Germany was negative. He was seen as a traitor who caused many German soldiers to die. However, some people started to see him differently. In 1953, a magazine argued that Sorge was a German patriot who wanted to bring down Hitler.

In 1961, a movie called Who Are You, Mr. Sorge? was made. It was popular in the Soviet Union. In November 1964, twenty years after his death, the Soviet government gave Sorge the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. Sorge's partner, Hanako Ishii, received a Soviet pension until her death in 2000. In the 1960s, the KGB (Soviet secret service) started celebrating "hero spies." Sorge became one of them.

There is a monument to Sorge in Baku, Azerbaijan. Sorge also appears in Osamu Tezuka's Adolf manga. In 2003, the Japanese film Spy Sorge was made about his life. In 2016, a train station in Moscow was named after Sorge. A Russian TV series about him was filmed in 2019.

What People Said About Sorge

Many famous people have commented on Richard Sorge:

- "A devastating example of a brilliant success of espionage." – Douglas MacArthur, General of the Army

- "His work was impeccable." – Kim Philby

- "In my whole life, I have never met anyone as great as he was." – Mitsusada Yoshikawa, Chief Prosecutor in the Sorge trials

- "Sorge was the man whom I regard as the most formidable spy in history." – Ian Fleming

- "Richard Sorge was the best spy of all time." – Tom Clancy

- "The spy who changed the world." – Lance Morrow

- "Richard Sorge's brilliant espionage work saved Stalin and the Soviet Union from defeat in the fall of 1941, probably prevented a Nazi victory in World War II and thereby assured the dimensions of the world we live in today." – Larry Collins

- "The spies in history who can say from their graves, the information I supplied to my masters, for better or worse, altered the history of our planet, can be counted on the fingers of one hand. Richard Sorge was in that group." – Frederick Forsyth

- "Stalin's James Bond." – Le Figaro

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |