Tzʼutujil people facts for kids

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 106,012 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Tzʼutujil | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Kʼicheʼ, Kaqchikel |

The Tzʼutujil people are one of the 22 Maya groups living in Guatemala. They are part of the 25 different groups in this country, which also include the Xinca, Garífunas, and Ladinos. About 100,000 Tzʼutujil people live near Lake Atitlán. Their old capital, before the Spanish arrived, was Chuitinamit, close to Santiago Atitlán. The Tzʼutujil nation was a key part of the ancient Maya civilization.

When the Spanish came in the 1500s, they brought a new religious system called cofradía. Later, in the 1800s, the Tzʼutujil people began to use a capitalist economy.

The Tzʼutujil are known for keeping their traditional ways of life and religious practices alive. Weaving and special songs have always been important for their religion. Some Tzʼutujil also follow Evangelical Protestantism or Roman Catholicism. They speak the Tzʼutujil language, which is part of the Mayan language family.

Contents

History of the Tzʼutujil People

Early History

The Tzʼutujil people appeared during the Post-Classic period (around 900 to 1500 AD) of the Maya civilization. They lived in the southern area around Lake Atitlán, in what is now the Solola region of Guatemala.

The ancestors of the Tzʼutujil came from Tulán, an old capital of the Toltec people. They settled near Lake Atitlán and built their capital, Chiaa, which means "close to the water," on the hill of Chuitinamit. The leaders in Chiaa included a supreme lord, the Ahtz'iquinahay, and a lesser lord, the Tz’utujil, who gave the group its name. These leaders also managed cacao farms south of Santiago Atitlan. In the 1400s, the Ki’che Maya ruler, Quicab, stopped the Tz’utujil people from moving west by using military force.

In 1523, the Spanish conquistador Pedro de Alvarado, with help from the Kaqchikel Maya, defeated the Tzʼutujil in a battle near Panajachel. After this, the Tzʼutujil lost some of their lands and control of the lake.

Life Under Spanish Rule

New Religious Ways

In the 1500s, Franciscan Friars moved the Tzʼutujil capital to Santiago Atitlán. They built a monastery there, hoping it would be easier to teach the Tzʼutujil about Christianity away from Chuitinamit hill.

In 1533, the Spanish started cofradía groups in Guatemala to help spread Christianity. These groups were dedicated to specific Catholic saints. They also helped the Spanish collect money from the Maya people. The Tzʼutujil community usually had fewer than ten cofradías at a time. Even though these groups were meant for Catholic practices, the Tz’utujil people often blended them with their own traditional ways, like worshiping special images. Mayan leaders sometimes used the money collected by cofradías to bargain with priests for favors. If priests did not agree, the Mayan communities might protest by not paying them or by speaking out against them.

Population Changes

The Tzʼutujil population greatly decreased during the Spanish colonial era. For example, it went from about 72,000 people in 1520 to 5,300 by 1575. Experts believe this decline was due to diseases like smallpox and measles that came with the Spanish. Other reasons included working in gold mines and battles with the Spanish.

Land and Work in the 1900s

In the 1800s, Guatemala started using a capitalist economy. In the 1900s, Guatemalan leaders took farming lands from indigenous people and gave them to non-indigenous owners. These large farms were called fincas. At the start of the century, many Tz’utujil workers had to work on these fincas to pay off debts. By 1928, about 80% of Tz’utujil people were working this way. By 1990, many Tz’utujil people still did not have enough land to grow food for their families.

Events in Santiago Atitlán (1990)

In the 1980s, there was conflict near Lake Atitlán. A group called the Organization of People in Arms recruited people in the area. Over time, many Tz’utujil people were harmed. After a new election in 1985, the conflict lessened.

However, on December 1, 1990, some soldiers caused trouble in Santiago Atitlán. The next day, thousands of people from Santiago Atitlán protested peacefully. The soldiers then fired into the crowd, killing 14 people and injuring 21. Because of this event, the army was forced to leave Santiago Atitlán.

Tzʼutujil Today

Today, most Tzʼutujil people live in towns like San Juan La Laguna, San Pablo La Laguna, San Marcos La Laguna, San Pedro La Laguna, Santiago Atitlán, Panabaj, and Tzanchaj. Some also live in San Lucas Tolimán.

In 2005, a natural disaster caused by Hurricane Stan led to mudslides. Several hundred Tzʼutujil people died. Rescuers found 160 bodies from Panabaj and Tzanchaj, and 250 people were still missing from these towns.

Tzʼutujil Religion and Culture

The Holy World (Santo Mundo)

In the traditional Tz’utujil religion, Santo Mundo is the Holy World or the universe. It is seen as a living body that holds water and grows trees, flowers, and food. Mountains are thought to be its nose. Santo Mundo changes based on what people do. It is also seen as a place that holds the Maize God.

Santo Mundo has five directions: the center and four corners. The center, or main plaza, is called "the Heart." It is where four roads meet and has a church from the 1500s. The corners are where the sun, called "Our Father the Sun," rises and sets during the longest and shortest days of the year. The part of the sky where the sun travels is the world of the living. The area below the sun's path is the underworld.

Spirits and Beliefs

Tzʼutujil communities believe that spirits control nature, other spirits, and people's lives.

Traditional customs come from spirits called Nawals, also known as "Ancient Ones." These "Ancient Ones" are believed to be old Tz’utujil people who became divine. Their guardian spirit was Old Mam, a trickster god, who taught them the customs the Tz’utujil follow today. It is believed that when the Tz’utujil pray, make sacrifices, and give offerings to the Nawals, the Nawals give them health, good luck, and good weather for farming. Since the Spanish arrived, the Nawals have been honored in the cofradías.

Jawal spirits include guardians, or chalbeij, who control different places on Earth. There are also Spirit Lords called Martins, who are thought to be new forms of San Martín, the Spirit Lord of Earth. The Martins are believed to control nature. In the cofradías, statues of Catholic saints, or "Santos," are seen as forms of these Spirit Lords. The highest spirit is called Dio's, a name that comes from the Spanish word for God, Dios, but it represents a different deity.

Life Cycle and Time

The Tz’utujil people see time as a cycle, not a straight line. They follow a concept called Jaloj-K’exoj, which has two types of change: jal and kex. Jal is the change that happens to a person as they grow older. Kex is a change that shows how generations pass on, often through reincarnation. Children are thought to be new forms of other family members, usually grandparents.

The Tz’utujil explain Jaloj-K’exoj using the maize (corn) plant. When a maize plant dies, it drops seeds, which is like a human being born. The plant's growth shows a person aging and going through jal. When the plant dies, it scatters its seeds, starting the process again for a new plant. This symbolizes how individuals and their ancestors are connected through time.

Traditional Songs

The Tz’utujil use traditional songs, called b’ix, to connect with the spiritual world. A person who sings these songs is called an ajb’ix, or songman. The songs are used to thank spirits, protect people from sickness or bad magic, and sometimes to cause trouble for enemies. There are also courting songs that compare feelings of love to how rain helps crops grow.

The Importance of Weaving

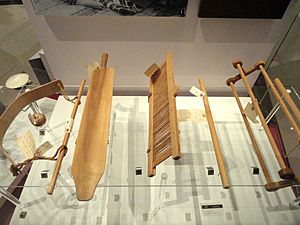

For the Tz’utujil, weaving is linked to the idea of fertility. Mayan people see the moon as an ancestral Grandmother and the goddess of weaving and giving birth. Making woven items is seen as a birthing process. For example, the rope in the loom, called yujkut, represents the umbilical cord. The sticks on the loom represent thirteen female deities called the Ixoc Ahauaua.

Tz’utujil women use a backstrap loom for weaving. Traditionally, they used x’cajcoj zut fabric. X’cajoj is the brown cotton material, and zut means the cloth is longer than it is wide. Today, women often use store-bought yarns, which allows for more colors. However, Tz’utujil weavings always have a yellow stripe in the middle and six silk tassels. Yellow means richness, and the yellow stripe stands for the "Abundance Road," which is the path the sun takes from 6 AM to 6 PM. Four silk tassels are placed on each corner of the cloth, with one tassel on each of the shorter sides. The tassels on the corners represent the sun rising and setting during the solstices. The long sides of the cloth symbolize the sun's path between noon and midnight.

Economy and Daily Life

Tourism has created a market for the talented Tzʼutujil artists and weavers. They are known for their creative and unique works. While tourism is growing, many Tzʼutujil still farm in traditional ways. Their main crops are coffee and maize (corn). They also grow beans, fruit, and vegetables. The Tzʼutujil farm on volcanic plains and trade their crops with other indigenous groups in nearby towns.

In Santiago Atitlán, work is divided by gender. Men farm, gather firewood, and do business activities. Women cook, get water, weave, and shop. It is said that few couples get divorced because they need each other to do these different tasks for the family to survive. Also, single adults are sometimes seen as needing to do the work of both genders to support themselves.

San Juan is one of three Tzʼutujil communities where artists have used a style called Arte Naif. They use this art to show their cultural traditions, beliefs, ceremonies, and daily life. This art form and some of its best Tzʼutujil artists have been featured in a special book called Arte Naif: Contemporary Guatemalan Mayan Painting (1998), supported by UNESCO. The weavers in San Juan are among the few indigenous artists who make their own dyes for their yarns, mostly from local plants.

See also

In Spanish: Zutuhil para niños

In Spanish: Zutuhil para niños