United States Court of Private Land Claims facts for kids

The United States Court of Private Land Claims was a special court that existed from 1891 to 1904. Its main job was to decide who truly owned certain lands in the American Southwest. These lands were located in the territories of New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah, as well as in the states of Nevada, Colorado, and Wyoming. The court helped sort out land claims that were promised to people under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican-American War.

Contents

How the Court Started

Before the United States took over the Southwest, the Spanish (1598–1821) and Mexican (1821–1846) governments had given out many land grants. These grants went to individuals and communities.

The Treaty and Land Promises

When the Mexican–American War ended in 1848, the United States gained these territories through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. This treaty included a promise in Article VIII to protect the property rights of Mexican citizens and former Mexican citizens. However, the U.S. Senate removed Article 10 when they approved the treaty. This article would have automatically guaranteed all land grants given by Spain and Mexico. Because it was removed, people had to prove their land claims.

Early Efforts and Problems

In 1851, the U.S. Congress passed a law to protect property rights from the treaty. This first law only dealt with Spanish and Mexican land grants in California. Congress focused on California because it was already a busy state, and they wanted to encourage more people to settle there.

Later, in 1854, Congress created the office of the Surveyor General of New Mexico. This person's job was to find out about "all claims to lands under the laws, usages, and customs of Spain and Mexico." At first, Congress tried to handle each land grant separately. The House of Representatives even had a special Committee on Private Land Claims. But by 1880, this system became very corrupt. Decisions were made based on politics, not on what was fair or legal. This led to a stop in proving any land claims for ten years.

Creating the Special Court

Because of these problems, the U.S. Congress decided to create a new solution. In 1891, they established the Court of Private Land Claims. This court had five judges who were appointed for a specific time. The court was meant to exist only until December 31, 1895, but its existence and the judges' terms were extended several times until June 30, 1904.

This special court was given the power to handle land claims in New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, Colorado, and Wyoming. Many of these old Spanish or Mexican land grants had incomplete paperwork. This was partly because those governments didn't always give out official deeds. Records were also kept in different places, like at the local, state, or even royal levels.

How the Court Worked

Soon after the judges and the U.S. attorney for the court, Matt G. Reynolds, were chosen in May 1891, they met in Denver. They organized how the court would operate.

Where Cases Were Heard

- Cases about land grants in Colorado were heard in Denver.

- Cases from New Mexico were decided in the federal courthouse in Santa Fe.

- Cases from Arizona were heard in Tucson and Phoenix.

The Court's Decisions

The court heard a total of 301 cases. These cases involved more than 36 million acres (about 150,000 square kilometers) of land. However, the court only approved 87 land grants. These approved grants covered about 3 million acres (about 12,000 square kilometers), which was less than 10% of the land claimed.

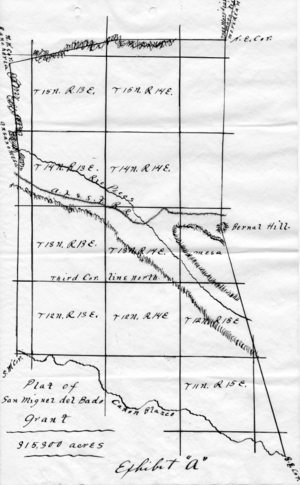

Many of the approved grants were also made smaller than what was originally claimed. For example, the Cañon de Chama Grant was reduced from 200,000 acres to just 1,500 acres (from 800 to 6 square kilometers). Any land from claims that were rejected by the court, or by the U.S. Supreme Court on appeal, became public land owned by the United States.

Challenges for the Court

The court faced many difficulties. One big problem was the old Spanish system of describing land using "metes and bounds." This meant using natural landmarks to mark boundaries. After a century or two, these old landmarks were very hard to find.

Another challenge was that the length of a vara (a Spanish yard) could change depending on when the land grant was made. Also, a grant might describe a boundary as the faldas (Spanish for "skirt") of the mountains. This could mean anywhere from the edge of the foothills to the timberline, making it very unclear.

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |