United States v. White Mountain Apache Tribe facts for kids

Quick facts for kids United States v. White Mountain Apache Tribe |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Decided March 4, 2003 | |

| Full case name | United States v. White Mountain Apache Tribe |

| Citations | 537 U.S. 465 (more)

123 S. Ct. 1126; 155 L. Ed. 2d 40

|

| Prior history | White Mountain Apache Tribe v. United States, 46 Fed.Cl. 20 (1999); White Mountain Apache Tribe v. United States, 249 F.3d 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2001) |

| Holding | |

| Affirmed Circuit Court, held that when the federal government used land or property held in trust for an Indian tribe, it had the duty to maintain that land or property and was liable for any damages for a breach of that duty. | |

| Court membership | |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Souter, joined by Stevens, O'Connor, Ginsburg, Breyer |

| Concurrence | Ginsburg, joined by Breyer |

| Dissent | Thomas, joined by Rehnquist, Scalia, Kennedy |

| Laws applied | |

| ; 28 U.S.C. § 1505 | |

United States v. White Mountain Apache Tribe was a big case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States in 2003. The Court ruled 5 to 4 that if the United States government holds land or property for a Native American tribe, it must take care of that property. If the government doesn't maintain it, it can be held responsible for any damage.

This case was about the White Mountain Apache Tribe in Arizona. In the 1870s, the tribe was given a reservation. The case focused on Fort Apache, a group of buildings on the reservation. In 1960, the United States Congress officially transferred these buildings to the tribe.

Even though the tribe owned the Fort Apache buildings, the government held them "in trust." This meant the government was in charge of them and used them for an Indian school. Over time, fewer students attended the school. The tribe wanted to use the buildings and have them recognized as a historic site. When the government was ready to give the property back, the tribe found the buildings were in bad shape. So, they sued the government for damages.

A lower court first said the tribe couldn't claim damages. But a higher court, the Circuit Court of Appeals, disagreed. They said the government had a duty to care for the property. The government then asked the Supreme Court to review the case. The Supreme Court agreed with the Circuit Court. They said the government had a duty to maintain the property because it held it in trust and used it.

Contents

What Happened Before the Case?

History of Fort Apache

In 1870, the United States Army built Fort Apache in Arizona. It was an active military base until 1922. Then, it was given to the Department of the Interior (DOI). Between 1871 and 1877, President Ulysses S. Grant used special orders to create the Fort Apache Indian Reservation. The fort itself was kept by the government. About 400 acres (1.6 km²) were set aside for the Theodore Roosevelt Indian School.

The school first taught 250 Navajo and Hopi children. More buildings were added for them. From 1933 to 1939, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) used the site for a school that studied an eye disease called trachoma. During World War II, students from many different tribes attended the school. In the 1950s, the school focused on job training. By 1960, other tribes started getting their own schools. This caused fewer students to attend the Fort Apache school.

In 1960, Congress decided that Fort Apache would be held in trust for the White Mountain Apache Tribe. However, the DOI could still use the property for "administrative or school purposes." By the 1970s, most tribes had their own schools. The Fort Apache school usually had fewer than 100 students. With fewer students, the BIA budget for Fort Apache also dropped. This led to buildings not being properly cared for, and some were even torn down.

The tribe decided to get the site listed on the National Historic Registry. In 1976, the National Park Service named it a National Historic Site. By 1993, the tribe had a plan to save the buildings. They also had a study done to see how much it would cost to fix the property. The U.S. government admitted that some of the 35 buildings were in bad shape. But they said the rest were well-maintained. In 1998, the World Monuments Fund listed the site as one of the 100 most endangered sites.

The Tribe's Lawsuit

In 1999, the tribe sued the government in a special court called the United States Court of Federal Claims. They asked for $14 million because the DOI had not taken care of the buildings. The tribe argued that the U.S. government had full control over the buildings. They said letting them fall apart broke the trust relationship set up by the 1960 law.

The government tried to get the lawsuit dismissed. They argued that the tribe couldn't sue for money without Congress specifically saying they could. They also said the time limit for filing such a lawsuit had passed. The trial court agreed with the government and dismissed the case.

Appeal to a Higher Court

The tribe then appealed their case to the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. This court looked at different federal laws. They found that these laws required the DOI and BIA to maintain historic buildings and Indian trust properties. However, these laws didn't say anything about paying money for damages.

Then, the court looked closely at the 1960 law. They decided that this law did create a trust relationship that allowed for money damages. They explained that a trust needs three things: a trustee (the U.S. government), a beneficiary (the tribe), and the property being held in trust (the land and buildings). The court said that since the U.S. government had full control over how the buildings were used and maintained, it had a special duty to the tribe. This duty meant the tribe could ask for money for damages. The court sent the case back to the trial court to continue. The U.S. government then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision

Arguments in Court

Lawyers for both sides presented their arguments to the Supreme Court. The government argued that the 1960 law did not say they had to pay money if they broke their trust duties. They said that even if a trust was formed, the tribe couldn't get damages without Congress clearly allowing it. They believed that "in trust" just meant the land couldn't be sold or taxed by the state.

The lawyer for the White Mountain Apache Tribe argued that when the 1960 law used the word "trust," it meant the government could be held responsible for money damages. They said that since a trust was legally formed, a law called the Indian Tucker Act allowed the tribe to sue for damages. The tribe also pointed out that the trust relationship is a very important part of Native American law.

The Court's Opinion

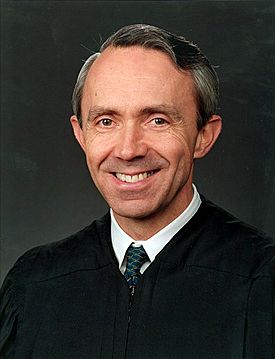

Justice David Souter wrote the main opinion for the Supreme Court. He explained that to sue the U.S. government, there must be a clear law that allows it. He said the Indian Tucker Act allowed this lawsuit if another federal law created the right to sue.

Justice Souter talked about two earlier cases, United States v. Mitchell I and United States v. Mitchell II. In Mitchell I, the government held land in trust to protect it from being sold or taxed, but the tribe controlled the land. In that case, the government didn't have a special duty to manage the land. But in Mitchell II, the government held land in trust and actively controlled it through rules about timber. In that case, the government did have a special duty to the tribe.

Justice Souter said that the 1960 law for Fort Apache was like Mitchell I because it set up a trust. But it also went further, allowing the government to use the land and buildings for a school. This control was as strong as the control in Mitchell II. Since the government had full use and control of the property, it couldn't "allow it to fall into ruin."

The Court rejected the government's arguments. They said that the idea the 1960 law "carved out" the buildings for government use didn't make sense with the law's words. They also said that just because the law didn't specifically say "money damages" didn't mean damages weren't allowed. Justice Souter said the Court would continue to use a "fair inference" from the law to decide if damages are allowed. Finally, the government argued that the only solution should be to force them to repair the buildings, not pay damages. Justice Souter said this was wrong and would just delay the cost.

The Supreme Court agreed with the Circuit Court's decision. They sent the case back to the lower court to follow their ruling. Justices Stevens, O'Connor, Ginsburg, and Breyer agreed with Justice Souter's opinion.

Agreeing with the Majority

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote a separate opinion, agreeing with the main decision. She explained more about why the government should pay for damages when it mismanages property. She said the Court's decision fit with other cases where the government controlled property in a way that didn't meet its duties. She believed the government clearly failed its duties to the tribe. Justice Breyer also agreed with Justice Ginsburg.

Disagreeing with the Majority

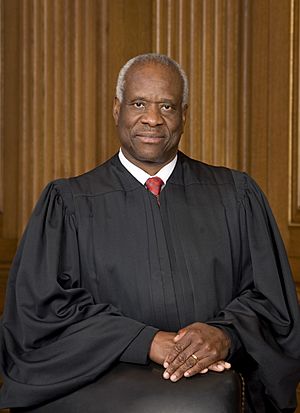

Justice Clarence Thomas wrote an opinion disagreeing with the majority. Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justices Scalia and Kennedy joined him. Justice Thomas argued that the law must be "fairly interpreted" to allow money damages. He felt the majority used a new test of "fair inference." He thought the case was more like Mitchell I, where the government didn't have a duty to manage the property in detail. He believed that without Congress clearly saying the U.S. government was responsible for money damages, there should be no such finding.

What Happened After the Case?

Because the government lost the case, they settled with the tribe in 2005. They paid the tribe about $12 million. In 2007, the government also gave 27 buildings to the tribe, along with the money and interest. The Fort Apache Heritage Foundation, a group created by the tribe, now manages these buildings.

This case, along with the Mitchell I, Mitchell II, and Navajo Nation cases, helps define something called the Indian Trust Doctrine. This doctrine explains the special relationship and duties the U.S. government has toward Native American tribes and their lands. After this case, the U.S. government has tried to take steps to reduce how much they might have to pay in future trust claims from tribes.