Vilém Flusser facts for kids

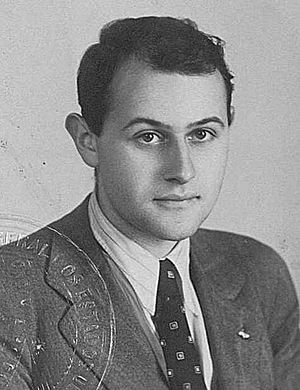

Vilém Flusser (born May 12, 1920 – died November 27, 1991) was a philosopher, writer, and journalist. He was born in Prague, which was then part of Czechoslovakia. He lived for a long time in São Paulo, Brazil, where he became a Brazilian citizen. Later, he lived in France. He wrote his books and articles in many different languages.

Early in his career, Flusser was interested in the ideas of thinkers like Martin Heidegger and in philosophies like existentialism. Later, he focused on the philosophy of communication and how art is made. He thought about how history has two main periods: one where people focused on images, and another where they focused on texts. He believed that sometimes people took these too far, leading to "image worship" or "text worship."

Contents

Vilém Flusser's Life Story

Flusser was born in 1920 in Prague, Czechoslovakia. His family were Jewish intellectuals. His father, Gustav Flusser, studied math and physics, even with Albert Einstein. Vilém went to German and Czech primary schools and then a German high school.

In 1938, Flusser began studying philosophy at the Charles University in Prague. In 1939, after the Nazis took over, Flusser moved to London with Edith Barth, who later became his wife, and her parents. He studied for a short time at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Sadly, Vilém Flusser lost all of his close family members in German concentration camps during World War II. His father died in Buchenwald in 1940. His grandparents, mother, and sister were sent to Auschwitz and then to Theresienstadt, where they were killed.

The next year, he moved to Brazil and lived in both São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. He worked for a Czech import/export company and then for a company that made radios.

In the 1960s, he started working with the Brazilian Institute for Philosophy in São Paulo. He published articles and became part of the Brazilian intellectual community. During this time, he taught at several schools in São Paulo. He was a lecturer for the philosophy of science at the University of São Paulo and a professor of communication philosophy at other schools. He also took part in art events, like the Bienal de São Paulo.

From the 1950s, he taught philosophy and worked as a journalist. His first book, Língua e realidade (Language and Reality), was published in 1963. In 1972, he decided to leave Brazil. Some people say it was because it became difficult to publish his work due to the military government. Others disagree, saying his work on communication and language was not a threat to the military. Also, in 1970, the Brazilian military government changed the University of São Paulo, and many philosophy teachers, including Flusser, had to leave.

First, he moved to northern Italy. Then, he lived in Germany and southern France. Towards the end of his life, he wrote a lot and gave many talks about media theory. He also explored new topics like the philosophy of photography and technical images. He died in 1991 in a car accident near the Czech–German border. He was on his way to visit his hometown, Prague, to give a lecture.

Vilém Flusser was the cousin of David Flusser.

Vilém Flusser's Philosophy

Flusser's essays are usually short, thought-provoking, and clear. They are often written in a style similar to newspaper articles. Experts say he was more of a "dialogic" thinker, meaning he liked to explore ideas through discussion, rather than building a strict "system" of thought. His early books, written in the 1960s, mostly in Portuguese, had a slightly different style.

Flusser's writings often connect to each other. He would explore certain topics deeply and then break them down into many short essays. His main interests included:

- How we know things (epistemology)

- Right and wrong (ethics)

- Beauty and art (aesthetics)

- What exists (ontology)

- The philosophy of language

- Signs and symbols (semiotics)

- The philosophy of science

- The history of Western culture

- The philosophy of religion

- The history of symbolic language

- Technology

- Writing

- Technical images (like photos)

- Photography

- Migration

- Media and literature

- And, especially later in his life, the philosophy of communication and how art is made.

His writings show his life of moving around. Most of his work was in German and Portuguese, but he also wrote in English and French. Because his writings in different languages were spread out in books and articles, his ideas about media and culture are only now becoming more widely known. The first book by Flusser published in English was Towards a Philosophy of Photography in 1984. He translated it himself.

Flusser's old papers and writings are kept at the Berlin University of the Arts.

Philosophy of Photography

In the 1970s and 80s, as computers began to change the world, Flusser wrote about photography. He believed that photographs were the first of many "technical images" that completely changed how we see the world. He thought photography was a huge turning point in history, as important as the invention of writing.

Before photography, ideas were often understood through written words. But photography brought new ways of seeing and knowing. Claudia Becker, who manages the Flusser Archive, explains that for Flusser, "photography is not just a way to copy images; it's a powerful cultural tool that helps us understand and create reality."

Flusser said that photographs are very different from "pre-technical images" like paintings. He explained that you can usually understand what a painter intended in a painting. But photographs, even though they look like exact copies of things, are harder to truly understand. This is because photos are made by a machine, or "apparatus." The camera works in ways that the person using it might not fully know or control.

For example, he described taking a photo like this:

The photographer tries to find the best view of a scene. But they can only do this within the limits of the camera. The photographer moves within specific ways of seeing space and time: how close or far, from above or below, from the front or side, how long the exposure is, and so on. The camera's settings already decide how the space and time around the scene will look to the photographer. These settings are like rules for them. They have to 'choose' within these rules: they must press the button.

Simply put, a person using a camera might think they are controlling it to make a picture exactly how they want it. But the camera's built-in program sets the rules for this action. It's the camera that shapes the meaning of the final image. Since photography is so important in our lives today, the camera's program affects how we look at and understand photos, and how we use them in our culture.

Flusser created special words that are still helpful for thinking about modern photography, digital images, and how we use them online. These include:

- Apparatus: A tool that changes the meaning of the world. This is different from simple tools that just change the world itself.

- Functionary: The photographer or person operating the camera. They are bound by the rules the camera sets.

- Programme: A system where chance becomes a certainty. It's like a game where every possible outcome, even the most unlikely, will happen if the game is played long enough.

- Technical Image: The photograph is the first example. It looks like a traditional image but contains hidden, coded ideas that can't be easily understood right away.

While Flusser wrote some short essays about specific photographers, his main goal was to understand the media culture of the late 20th century. He wanted to explore the new possibilities and challenges that came with a world that was becoming more technical and automated.

Ideas About Home and Being Homeless

Flusser was deeply affected by losing his home city of Prague and by moving many times in his life. This experience shaped his writings and made him feel "homeless," because, as he said, "there are so many homelands that make their home in me." His own life helped him study how people communicate and connect.

Communication, which fills the gaps between different people's views, is part of culture. It relies on patterns we learn unconsciously at home. Language is a big part of how we think. Flusser wondered what happens when someone loses their home and their old connections.

He looked at two German words for "home": "Heimat" (homeland) and "Wohnung" (house). He argued that "home" is not a value that lasts forever. A person is connected to their "Heimat" by invisible ties like people, traditions, and language. These ties are often hidden from our conscious mind. Only when a person leaves their home do they become aware of these ties, which show up as unconscious judgments. These unconscious "habits stop us from noticing bits of information" and make our usual surroundings feel comfortable and nice. For Flusser, this explains "love for a fatherland."

A person who is "homeless" (meaning they have moved to a new place) must not only consciously learn the habits of their new home but also forget them again. If these habits become too conscious, they might seem ordinary, possibly revealing the true nature of the new place. Flusser described a debate between the "ugly stranger" who can reveal the truth and the "beautiful native" who fears the new person because they threaten their habits. Flusser used his experience in Brazil, a country with lots of immigration, to show that people can free themselves from old habits and form new connections, creating a new "homeland."

However, unlike the "homeland" that one can leave, the "home" as a house is a necessary part of being human. It helps a person process information by dividing their world into what is familiar (home) and what is new or unusual. The familiar environment is needed to recognize what is unusual when it enters one's home. Flusser connected this idea to Hegel's ideas about the relationship between home and the unusual, or generally, about consciousness.

Vilém Flusser's Works

Books

- Das XX. Jahrhundert. Versuch einer subjektiven Synthese, 1950s (in German)

- Língua e realidade, 1963 (in Portuguese)

- Jazyk a skutečnost, 2005 (in Czech)

- A história do diabo, 1965 (in Portuguese)

- Die Geschichte des Teufels, 1993 (in German)

- Příběh ďábla, 1997 (in Czech)

- The History of the Devil, 2014 (in English)

- Da religiosidade: a literatura e o senso de realidade, 1967 (in Portuguese)

- La force du quotidien, 1973 (in French)

- Le monde codifié, 1974 (in French)

- O mundo codificado, 2007 (in Portuguese)

- Orthonature/Paranature, 1978 (in French)

- Natural:mente: vários acessos ao significado da natureza, 1979 (in Portuguese)

- Vogelflüge: Essays zu Natur und Kultur, 2000 (in German)

- Natural:Mind, 2013 (in English)

- Pós-história: vinte istantâneos e um modo de usar, 1983 (in Portuguese)

- Post-History, 2013 (in English)

- Für eine Philosophie der Fotografie, 1983 (in German)

- Towards A Philosophy of Photography, 1984 (in English)

- Filosofia da caixa preta. Ensaios para uma futura filosofia da fotografia, 1985 (in Portuguese)

- Per una filosofia della fotografia, 1987 (in Italian)

- For fotografiets filosofi, 1987 (in Norwegian)

- En filosofi för fotografin, 1988 (in Swedish)

- Hacia una filosofía de la fotografía, 1990 (in Spanish)

- A fotográfia filozófiája, 1990 (in Hungarian)

- Bir fotoğraf felsefesine doğru, 1991 (in Turkish)

- 写真の哲学のために : テクノロジーとヴィジュアルカルチャー, 1992 (in Japanese)

- Za filosofii fotografie, 1994 (in Czech)

- Taipei: Yuan-Liou, 1994 (in Chinese)

- Pour une philosophie de la photographie, 1996 (in French)

- Ensaio sobre a fotografia: para uma filosofia da técnica, 1998 (in Portuguese)

- Thessaloniki: University Studio Press, 1998 (in Greek)

- 사진의 철학을 위하여, 1999 (in Korean)

- Za filozofiju fotografije, 1999 (in Serbian)

- Towards A Philosophy of Photography, 2000 (in English)

- Una filosofía de la fotografía, 2001 (in Spanish)

- Za edna filosofia na fotografiata, 2002 (in Bulgarian)

- Pentru o filosofie a fotografie, 2003 (in Romanian)

- Za edna filosofia na fotografira, 2002 (in Russian)

- Ku filozofii fotografii, 2004 (in Polish)

- Filozofija Fotografije, 2007 (in Croatian)

- Een filosofie van de fotografie, 2007 (in Dutch)

- Za filosofiyu fotografii, 2008 (in Russian)

- K filozofiji fotografije, 2010 (in Slovenian)

- Ins Universum der technischen Bilder, 1985 (in German)

- A technikai képek univerzuma felé, 2001 (in Hungarian)

- Do universa technických obrazů, 2002 (in Czech)

- O universo das imagens tecnicas. Elogio da superficialidade, 2010 (in Portuguese)

- Into the Universe of Technical Images, 2011 (in English)

- Hacia el universo de las imagenes technicas, 2011 (in Spanish)

- Die Schrift, 1987 (in German)

- Az írás. Van-e jövője az írásnak?, 1997 (in Hungarian)

- 글쓰기에 미래는 있는가, 1998 (in Korean)

- A Escrita. Ha futuro para a escrita?, 2010 (in Portuguese)

- Does Writing Have a Future?, 2011 (in English)

- with Louis Bec, Vampyroteuthis infernalis, 1987 (in German)

- Vampyroteuthis infernalis, 2011 (in Portuguese)

- Vampyroteuthis Infernalis, 2011 (in English)

- Vampyroteuthis Infernalis: A Treatise, with a Report by the Institut Scientifique de Recherche Paranaturaliste, 2012 (in English)

- Krise der Linearität, 1988 (in German)

- "The Crisis of Linearity", 2006 (in English)

- Angenommen. Eine Szenenfolge, 1989 (in German)

- with Jean Baudrillard and , Philosophien der neuen Technologien, 1989 (in German)

- Gesten. Versuch einer Phänomenologie, 1991 (in German)

- Bodenlos: Eine philosophische Autobiographie, 1992 (in German)

- Bezedno: filosofická autobiografie, 1998 (in Czech)

- Bodenlos: Uma autobiografia filosofica, 2010 (in Portuguese)

- A Dúvida, 1999 (in Portuguese)

- On Doubt, 2014 (in English)

Selected Articles and Papers

- "Filosofia da linguagem", 1966 (in Portuguese)

- "In Search of Meaning (Philosophical Self-portrait)", 2002 (in English)

- "The Photograph as Post-Industrial Object: An Essay on the Ontological Standing of Photographs", 1986 (in English)

- "Fernsehbild und politische Sphäre im Lichte der rumänischen Revolution", 1990 (in German)

- "On Memory (Electronic or Otherwise)", 1990 (in English)

- "Die Stadt als Wellental in der Bilderflut", 1990 (in German)

- "The City as Wave‐Trough in the Image‐Flood", 2005 (in English)

- "Projektion statt Linearität", 1991 (in German)

- "Räume", 1991 (in German)

- "L'image-calcul. Pour une nouvelle imagination", 2015 (in French)

See Also

In Spanish: Vilém Flusser para niños

In Spanish: Vilém Flusser para niños

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |