Virginia big-eared bat facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Virginia big-eared bat |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Photo of a Virginia big-eared bat roosting at a large hibernaculum | |

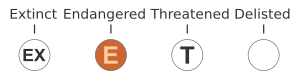

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Family: | Vespertilionidae |

| Genus: | Corynorhinus |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: |

C. t. virginianus

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Corynorhinus townsendii virginianus Handley, 1955

|

|

The Virginia big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii virginianus) is a special kind of bat that needs our help. It is one of two endangered types of the Townsend's big-eared bat. You can find these bats in Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina, and Kentucky.

In 1979, the US Fish and Wildlife Service officially called this bat an endangered species. This means it is at risk of disappearing forever. There are about 20,000 of these bats left. Most of them live in West Virginia. The Virginia Big-Eared Bat is even the official state bat of Virginia!

Contents

About the Virginia Big-Eared Bat

The Virginia big-eared bat has soft, long fur. Its fur can be light to dark brown, depending on how old the bat is. The fur is the same color from its base to its tip.

This bat is one of the biggest cave-dwelling bats in its area. It weighs between 7 and 12 grams. That's about as much as a few paper clips! You can easily spot this bat by its very large ears. These ears are over 2.5 centimeters long. When the bat is resting, its ears can reach back to half the length of its body. It also has a round-shaped nose and long nostrils. Its whole body is about 98 millimeters long. Its forearms are 39 to 48 millimeters, its tail is about 46 millimeters, and its back foot is about 11 millimeters.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Virginia big-eared bats mate in the fall and winter. Female bats can store the male's sperm until winter or spring. This is when they release their eggs. The mothers are pregnant for about 3 months. They usually have one baby, called a pup, in May or June. In about 2 months, the pups grow fully. They are then able to fly away from their roost, which is their home.

Where They Live and What They Do

These bats live in caves all year long. They prefer caves that are surrounded by oak-hickory forests. You usually find them in mountainous areas with limestone rock. During the time when mothers have their babies, the female bats stay in these caves. Most male bats do not stay with the females during this period.

Virginia big-eared bats do not migrate, meaning they do not travel far. They usually stay close to their caves. In the winter, they hibernate instead of moving to warmer places. These bats usually only leave their caves to hunt for food. They hunt and eat at night. In Virginia, they hunt in open fields. In Kentucky, they hunt near cliffs. They use their special sonar, called echolocation, to find insects. They fly along the edges of forests where they hunt. These bats help us by eating insects that can harm plants. They hunt small moths, beetles, flies, lacewings, bees, and wasps.

Things that threaten these bats include loud noises, bright lights, and people being too close to them.

What Virginia Big-Eared Bats Eat

The Virginia big-eared bat mainly eats insects. Small moths make up a big part of their diet.

These bats are insectivores. This means they are meat-eaters that mostly eat insects. Virginia big-eared bats hunt for flying insects in wooded areas during the evening and early morning. Bats have a very strong sense of hearing. This helps them quickly find and catch their prey.

How They Hunt: Echolocation

The bat's strong hearing allows them to echolocate. Echolocation is a natural ability bats have. They make sounds that bounce off objects around them. This helps them find their prey while flying in the dark. They typically hunt insects like moths, beetles, termites, mosquitoes, and flies. Without echolocation, these bats would not be able to find their food.

Scientists have studied what these bats eat. They looked at bat droppings. In one study, 97% of the droppings showed that the bat had eaten Lepidoptera. This group of insects includes butterflies and moths.

Another study in Kentucky looked at the food found in bats' stomachs and droppings. It showed that in that area, Virginia Big-Eared Bats mostly ate Lepidoptera (moths) and Coleoptera (beetles). They also ate spiders, crickets, roaches, flies, ants, wasps, and bees.

Where They Live and Their Homes

Virginia big-eared bats live in separate groups in eastern Kentucky, eastern West Virginia, southwestern Virginia, and northwestern North Carolina. They do not migrate. They live in caves all year round. This type of Townsend's big-eared bat prefers caves made from limestone rock. The areas where they are found usually have oak-hickory or beech-maple-hemlock forests.

Townsend's big-eared bats are usually found west of the Appalachian Mountains. This means there is a large distance between different types of these bats. Scientists believe this separation has been there since the last ice age. It is hard for these bats to find good homes. This is because they need very specific temperatures and humidity levels in their caves.

Bat Homes and Behavior

Bats have been seen flying high above cliffs in the Daniel Boone National Forest. Studies have shown different results for where bats are most active. Some show high activity on cliffs, others in forests, and some in open fields. Bats were rarely seen flying over open areas or over places where many people live. The farthest a Virginia Big-Eared Bat has been seen hunting was 8.4 kilometers from its home cave. Scientists found this out using radio tracking.

A study in Lee County, Kentucky, looked at hills with sandstone cliffs. The heights of these hills ranged from 182 to 424 meters. Limestone under the sandstone created caves. These caves are perfect homes for the Virginia big-eared bats. How bats use their hunting areas can be very different between groups that live far apart. In Kentucky, old fields have been important hunting spots for these bats. So, these old fields should be protected and kept away from people in the Daniel Boone National Forest. This way, the bats can continue to use them for hunting.

Homes and Seasons

During hibernation, these bats need a cool environment. The temperature should be between 32 and 54 degrees Fahrenheit (0 to 12 degrees Celsius). Virginia big-eared bats store fat in the winter for hibernation. If they are disturbed and the cave temperature changes, they must use up their fat to warm their bodies. This makes them very weak. If a maternity site (where mothers have babies) is disturbed, female bats might even leave their babies.

This is a main reason why these bats hibernate in tight groups. These groups are often found at the entrance of caves. This spot has the right temperature and good air flow. Maternity colonies are found in the warmer parts of the caves.

Most of these bats live in limestone caves. The warmth of the roost is very important for mothers when they are pregnant. The timing of maternity periods changes what mothers need in their homes. In Virginia, the number of bats in roosts decreased in late May to early June. In July, the bat population and night activity greatly increased. This shows that July is the most common time for breeding and having babies. In August, male bats moved and switched roosts a lot. However, it is not known where the males spend the rest of their summer.

Over 5,000 Virginia big-eared bats were found hibernating in Stillhouse Cave in the Daniel Boone National Forest of Kentucky. This is about 40 percent of all the bats of this type!

Protecting the Virginia Big-Eared Bat

People in West Virginia were the first to notice fewer Virginia big-eared bats in local caves. In 1976, there were only about 2,500 to 3,000 bats. The decline was thought to be caused by human activities. These include caving (spelunking) and just being present in caves where bats live. Bats do not like outside activity. Some bats might have also been taken by cave researchers because they look unique. Living in mines has also led to fewer bats.

Cutting down forests is also a problem. The Virginia Big-Eared Bat eats about 45 different types of moths. But 77.8% of these moths grow from caterpillars that need forest plants to survive. Destroying forests hurts the bats in two ways. It takes away their homes and reduces the number of insects they can eat.

The Virginia big-eared bat was listed as endangered on December 31, 1979. Five caves in West Virginia were named critical habitats for the bat. These caves were closed to the public. A plan to help the bats recover was suggested in 1984. This plan included putting gates on cave entrances preferred by the bats. This would stop people from disturbing them. Bat colonies would also be watched to count their numbers.

The recovery plan under the Endangered Species Act asked for several things:

- Watching bat populations using special infrared sensors that don't disturb them.

- Finding new important caves for the bats.

- Stopping human disturbance in caves by adding gates and signs.

- Making sure agencies protect caves that are homes for single bats.

- Preventing changes and damage to important bat homes.

- Getting and keeping support for protecting the species.

- Creating a plan for each bat colony to record its population and activity.

- Appointing a person to lead all recovery and research efforts.

In 2009, the bat population had increased by 77% since 1983. The increase in Virginia big-eared bat numbers is seen as a successful recovery. This is thanks to the Endangered Species Act.

Threat of White-Nose Syndrome

White-nose syndrome is a very serious disease. It is harming many North American bats that hibernate in caves. This disease has caused many bats to die. It is caused by a cold-loving fungus called Pseudogymnoascus destructans. The fungus starts to grow on bats during winter hibernation. This is when bats are in a deep sleep (torpor) and their bodies are less able to fight off sickness. The bat's body temperature during hibernation is perfect for the fungus to grow.

This fungus has affected 90% of bat species that hibernate in caves. Spores of Pseudogymnoascus destructans have been found on the Virginia big-eared bat. So far, no Virginia big-eared bats have died from White-nose syndrome. This is even though the disease has killed millions of other cave-dwelling bats. Scientists now think that the Virginia big-eared bat might have a natural way to fight off the disease. They believe a type of yeast that the bat "combs" over its body might stop the fungus from growing.