- This page was last modified on 17 October 2025, at 10:18. Suggest an edit.

Whitehurst & Son sundial (1812) facts for kids

The Whitehurst & Son Sundial is a special clock that uses the sun to tell time. It was made in Derby in 1812 by the nephew of a famous clockmaker, John Whitehurst. Today, you can see it at the Derby Museum and Art Gallery. This sundial is very accurate. It can tell you the time based on the sun's position (called local apparent time) and also the average time we use on our clocks (called local mean time). It's so precise, it can tell the time to the nearest minute!

Contents

Who Made It?

The Whitehurst family was well-known in Derby for being amazing mechanics. John Whitehurst (1713–1788) was born in Congleton. He moved to Derby and became a skilled maker of watches and clocks. Later, he moved to London to work as an Inspector of Weights. His nephew took over the family business, calling it Whitehurst & Son. The family was especially famous for making large clocks found in towers, known as turret clocks.

How Sundials Work

To build a sundial, you need to understand how the solar system works. Especially, you need to know how the sun creates a shadow on a flat surface. For this sundial, the surface is flat and horizontal. The shadow changes every day throughout the year. It also changes depending on where the sundial is located, especially its latitude (how far north or south it is).

This sundial is designed to show local apparent time. This means it shows the time based on the sun's exact position in the sky at that specific spot. So, the longitude (how far east or west it is) doesn't matter for this type of time. At noon, the sun is highest in the sky and directly south.

Our modern clocks use standard time, which is based on a specific point, like the Royal Observatory at Greenwich. Derby is a bit west of Greenwich. This means the sun reaches its highest point in Derby about 5 minutes and 52 seconds later than in Greenwich.

The Equation of Time

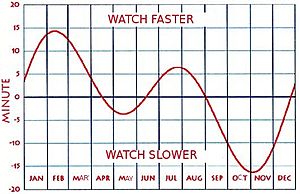

When telling time with a sundial, we also need to think about something called the equation of time. The Earth moves around the sun in a slightly oval shape. Because of this, the length of each day changes slightly throughout the year. For example, the difference from the average day length can be up to 16 minutes in November and February!

For a long time, people didn't really know about this difference. They only noticed it when they started comparing sundials with mechanical clocks. If a clock doesn't account for this difference, it measures average time. But if a clock is adjusted daily to match the sun's natural cycle, it measures local mean time.

Having a fixed noon and a fixed day length became very important for railway timetables. This is why Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) was chosen as the standard time. For the Midland Railway, GMT was adopted by January 1848.

This particular bronze sundial says "Whitehurst and Son/Derby/1812" on it. People believe it was made for George Benson Strutt. He was the younger brother of William Strutt, who was famous for cotton spinning. The sundial was likely made for George's home, Bridge Hill House, in Belper. The exact location of Bridge Hill House is slightly different from Derby. This small difference in location means the sundial needs a tiny adjustment to be perfectly accurate.

The Gnomon

The sundial is very strong and has a thick part called a gnomon. This is the stick that casts the shadow onto the dial plate. The dial plate isn't one full circle. It's two half-circles separated by the gnomon's thickness.

For this type of sundial, the angle of the gnomon to the dial plate is exactly the same as the latitude of its location. For Bridge Hill House, this angle is 53° 1′ 49″. The dial plate should be perfectly flat at that location. If you place the sundial somewhere else, you'd need to tilt the dial plate slightly to adjust for the new latitude. For example, if it's placed a little bit south, the tip of the gnomon needs to be raised a tiny bit.

The Dial Plate

In a horizontal sundial (sometimes called a garden sundial), the flat surface that gets the shadow is placed horizontally. The shadow doesn't move at a steady speed around the dial face. Because of this, the hour lines on the dial are spaced out using a special calculation.

The dial plate has hour lines carefully carved into it. These lines are figured out using a math formula. The formula helps determine the angle of each hour line from the noon line. The noon line always points towards true North.

The Calculations

The hour lines are calculated for each hour from 1 to 6. For example, to find the line for 3 hours after noon, specific numbers are put into the formula. This creates results like the ones below:

| One hour | 11.791779 degrees |

| Two hours | 24.219060 degrees |

| Three hours | 37.922412 degrees |

| Four hours | 53.460042 degrees |

| Five hours | 71.020970 degrees |

| Six hours | 90.000000 degrees |

The hour lines before noon are exactly the same. This is because the sundial is symmetrical. So, the lines for 11 AM, 10 AM, and so on are mirror images of the afternoon lines. Half-hour and minute lines are calculated in the same way.

Since the noon line is set exactly on the north-south line, and not adjusted for the time difference between Belper and Greenwich, we know this sundial tells Belper time.

Equation of Time Scales

An important feature on the dial plate is a pair of scales. These scales help you correct for the equation of time. One scale shows the date in months and days. Next to it, another scale shows how many minutes a clock would be running faster or slower on that specific day. It's labeled "Watch Slower" or "Watch Faster." For example, on April 15th, no correction is needed.

This sundial could be used to read the time shown by the sun. It could also be used to find the average time that clocks use. This was very practical! People could use the sundial to check their pocket watches. In 1812, watches weren't always perfectly accurate. By 1820, watchmaking had gotten much better, and a new part called the Lever escapement became popular. This meant watches didn't need to be checked as often.

Other Sundials

Another sundial made by Whitehurst, from around 1800, was sold for £1850 in 2005 in Derby.

Related pages

- Bibliography