Wife selling (English custom) facts for kids

Wife selling in England was a way for people to end a marriage that wasn't working. This practice likely started in the late 1600s. Back then, getting a divorce was almost impossible unless you were very rich.

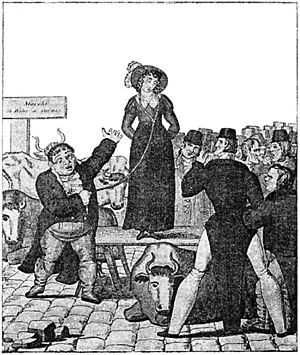

A husband would lead his wife with a rope (called a halter) around her neck, arm, or waist. Then, he would publicly auction her off to the person who offered the most money. This old custom is part of Thomas Hardy's 1886 novel The Mayor of Casterbridge. In the story, the main character sells his wife early on. This act stays with him and eventually causes his downfall.

This custom had no legal basis. People who did it were often charged with a crime, especially from the mid-1800s. However, the authorities sometimes didn't know what to do. One judge in the early 1800s said he didn't think he could stop these sales. Also, some local officials even made husbands sell their wives. This was to avoid having to support the family in workhouses (places where poor people lived and worked).

Wife selling continued in England until the early 1900s. James Bryce, a legal expert, wrote in 1901 that wife sales still happened sometimes. In one of the last known cases in England, a woman in a Leeds court in 1913 said her husband sold her to a co-worker for £1.

Contents

Why Did People Sell Wives?

The custom of wife selling in a "ritual form" (like an auction) seems to have started around the end of the 1600s. However, there's a record from 1302 of a man who "granted his wife by deed to another man." As newspapers became more popular in the late 1700s, more reports of wife selling appeared. People at the time saw it as a long-standing custom.

Marriage Rules

Before the Marriage Act 1753 was passed, there was no legal need for a formal church wedding in England. Marriages were not officially recorded. All that was needed was for both people to agree to marry. Girls could marry at 12 and boys at 14.

After marriage, women had very few rights. A husband and wife became one legal person, a status called coverture. The famous English judge Sir William Blackstone wrote in 1753 that a woman's legal existence "is suspended during the marriage." This meant she couldn't own property. Women were seen as their husband's property. But Blackstone also said that these rules were meant to protect women.

Ending a Marriage

In the past, there were five main ways to end a marriage in England.

- One way was to go to church courts for a separation. This was for reasons like disloyalty or cruelty. But it didn't allow either person to remarry.

- From the 1550s until 1857, getting a full divorce was very difficult and expensive. It needed a special law passed by Parliament. Even after 1857, when divorce became cheaper, it was still too costly for most poor people.

- Another option was a "private separation." This was an agreement between the husband and wife, written down by a lawyer.

- People could also simply leave each other. A wife might be forced out of her home, or a husband might move in with another woman.

- Finally, wife selling was an unofficial way to end a marriage. It was seen by poor people as a way to get a "divorce" when a couple was "tired of each other."

Some wives in the 1800s didn't like being sold. But there are no records of women resisting sales in the 1700s. Many women had no money or skills to support themselves. For them, a sale might have been the only way out of an unhappy marriage. Sometimes, the wife even insisted on the sale. For example, a wife sold in Wenlock Market in 1830 for 2s 6d (about £12 in 2018) was determined to go through with it. Her husband had doubts, but she told him, "I will be sold. I want a change."

For the husband, selling his wife meant he no longer had to support her financially. For the buyer, who was often the wife's secret lover, the sale protected him from legal trouble.

How a Wife Was Sold

It's not clear exactly when the custom of selling a wife at a public auction began. It seems to have been around the late 1600s. In 1692, a man named John Whitehouse sold his wife. In 1696, Thomas Heath was fined for living with another man's wife after buying her for "2d.q. the pound." Between 1690 and 1750, only eight other cases were recorded in England. By 1789, in Oxford, wife selling was called "the vulgar form of Divorce lately adopted." This suggests it was still spreading to different parts of the country. It continued in some form until the early 1900s.

The Sale Process

Most reports say the sale was announced beforehand, sometimes in a local newspaper. It was usually an auction, often held at a local market. The wife would be led by a halter (a rope or ribbon) around her neck or arm. Often, the buyer was already known, and the sale was a way to make the separation and new relationship official.

For example, in January 1815, John Osborne planned to sell his wife at Maidstone market. But since there was no market that day, the sale happened at a pub. His wife and child were sold for £1 to a man named William Serjeant. In July of the same year, a wife was brought to Smithfield market by coach and sold for 50 guineas and a horse. After the sale, "the lady, with her new lord and master, mounted a handsome curricle which was in waiting for them, and drove off, seemingly nothing loath to go."

While the husband usually started the idea, the wife had to agree to the sale. A report from 1824 in Manchester says a wife was "knocked down for 5s; but not liking the purchaser, she was put up again for 3s and a quart of ale." Often, the wife was already living with her new partner. Sometimes, a fight at home would lead to a wife being sold. But usually, the goal was to end a marriage in a way that felt like a legal divorce. In some cases, the wife even arranged her own sale and paid someone to buy her out of her marriage. This happened in Plymouth in 1822.

These "divorces" were not always permanent. In 1826, John Turton sold his wife Mary to William Kaye for five shillings. But after Kaye died, Mary returned to her husband, and they stayed together for 30 years.

Who Was Involved?

In the mid-1800s, people thought wife selling only happened among the poorest workers in remote areas. But studies show it was more common in areas with early industries. Out of 158 cases where jobs were known, the largest group (19) worked with livestock or transport. Fourteen worked in building, five were blacksmiths, four were chimney-sweeps, and two were described as gentlemen. This shows it wasn't just a custom for farmers. The most famous case was Henry Brydges, 2nd Duke of Chandos, a duke, who reportedly bought his second wife from a stable worker around 1740.

The prices paid for wives varied a lot. They ranged from £100 plus £25 for each of her two children in 1865 (about £15,000 in today's money) to as little as a glass of ale or even nothing. The lowest amount of money exchanged was three farthings (less than a penny). The usual price was between 2s. 6d. and 5 shillings. Money seemed less important than the idea that the sale was legally binding, even though it wasn't.

Some new couples even married again, which was bigamy (being married to two people at once). Officials often didn't know how to handle wife selling. Local church leaders and judges knew about it but seemed unsure if it was legal, or they simply ignored it. Some baptism records even mention it, like one from Essex in 1782: "Amie Daughter of Moses Stebbing by a bought wife delivered to him in a Halter." In 1784, a jury in Lincolnshire decided that a man who sold his wife couldn't get her back. This supported the idea that the sale was valid.

In 1819, a judge tried to stop a sale in Ashbourne, Derby. But the crowd threw things at him and chased him away. He later said that he didn't think he had the right to stop the sale. He felt it was a custom of the people that might be dangerous to take away by law.

In some cases, like Henry Cook's in 1814, the Poor Law authorities forced the husband to sell his wife. This was to avoid having to support her and her child in the Effingham workhouse. She was sold for one shilling, and the local parish paid for her journey and a "wedding dinner."

Where Sales Happened

By choosing a market for the sale, couples made sure many people saw their separation. This made it a widely known fact. The halter was a symbol. After the sale, it was given to the buyer to show the deal was done. Sometimes, people even made the buyer sign a contract. This stated that the seller was no longer responsible for his wife. In 1735, a successful wife sale was announced by a town crier. He told local traders that the former husband would not pay any debts his wife made. An advertisement in the Ipswich Journal in 1789 said, "no person or persons to intrust her with my name... for she is no longer my right."

In Sussex, inns and public houses were common places for wife selling. Alcohol was often part of the payment. For example, in 1898, a man sold his wife at a pub in Yapton. The buyer paid 7s. 6d. (about £45 in today's money) and a quart of beer. A century earlier in Brighton, a sale involved "eight pots of beer" and seven shillings (about £35 today). In Ninfield in 1790, a man traded his wife at the village inn for half a pint of gin. He later changed his mind and bought her back.

Public wife sales sometimes drew huge crowds. A sale in Hull in 1806 was delayed because of the large crowd. This suggests that wife sales were rare and popular events. Experts estimate about 300 wife sales happened between 1780 and 1850. This is much less than the tens of thousands of desertions (when a spouse simply left) during the same time.

Where Was It Common?

Wife selling seemed to happen all over England. But it was rare in nearby Wales, with only a few cases. In Scotland, only one case has been found. The English county with the most cases between 1760 and 1880 was Yorkshire, with 44. This was much more than the 19 cases in Middlesex and London during the same time. This is interesting because French drawings often showed an English nobleman, "Milord John Bull," selling his wife in London's Smithfield Market.

Samuel Pyeatt Menefee, an author, collected 387 cases of wife selling. The last one he found was in the early 1900s. Historian E. P. Thompson thought many of Menefee's cases were unclear. But he agreed that about 300 were real. With his own research, Thompson found about 400 reported cases.

Menefee believed the ritual copied livestock sales. The halter was a symbol, and wives were sometimes valued by weight, like animals. However, Thompson suggested that markets were chosen not because animals were sold there. Instead, they were public places where many people could witness the separation of a husband and wife. Sales often happened at fairs, outside pubs, or near famous landmarks.

There were very few reports of husbands being sold. From today's view, selling a wife like property is wrong. But most reports from the time suggest the women had some say. They were often described as "fine-looking," "buxom," or "enjoying the fun."

English settlers brought the custom of wife selling to the American colonies in the late 1600s and early 1700s. They believed it was a legal way to end a marriage. In 1645, a court in Hartford, Connecticut, fined Baggett Egleston for "bequething his wyfe to a young man." In 1736, the Boston Evening-Post reported an argument between two men over a woman. One man had sold his "right" to her for fifteen shillings.

Changing Views

By the late 1700s, people started to dislike wife selling. In 1756, a sale in Dublin was stopped by women who rescued the wife. The husband was then put in the stocks (a device for public punishment). Around 1777, a wife sale in Carmarthenshire caused "a great silence" and "uneasiness" in the crowd. In 1806, when a man offered his wife for sale in Smithfield market, the public was angry and would have hurt him if police hadn't stepped in.

Reports of wife selling grew from two per decade in the 1750s to a peak of fifty in the 1820s and 1830s. As more cases happened, more people opposed the practice. It became seen as a custom that the upper classes felt they should stop. Women also protested, saying it was "a threat and insult to their sex." Judges became more active in punishing those involved. Some court cases confirmed that the practice was illegal.

Newspapers often spoke badly of wife selling. An 1832 report called it "a most disgusting and disgraceful scene." But it wasn't until the 1840s that the number of cases really started to drop. Thompson found 121 published reports between 1800 and 1840, but only 55 between 1840 and 1880.

Lord Chief Justice William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield thought wife sales were a trick. But few cases reported in newspapers led to court charges. The Times reported one such case in 1818. A man was charged for selling his wife at Leominster market for 2s. 6d. In 1825, a man named Johnson was charged for singing a song about his wife's good points to sell her at Smithfield. The police officer said the man had gathered a "crowd of all sorts of vagabonds" who were actually there to pick pockets. Johnson said he was just trying to earn money for his hungry children. The Lord Mayor warned him that such a practice was not allowed. In 1833, a woman was sold in Epping for 2s. 6d. The husband claimed he had been forced into marriage by the parish and had never lived with her. He was jailed for "having deserted his wife."

The return of a wife after 18 years leads to the downfall of Michael Henchard in Thomas Hardy's novel Mayor of Casterbridge (1886). Henchard, a cruel husband, sells his wife to a stranger. He becomes a successful mayor, but his wife's return years later causes him to lose everything.

The custom was also mentioned in a 19th-century French play, Le Marché de Londres. In 1846, writer Angus B. Reach complained that French people believed that in England, "a husband sells his wife exactly as he sells his horse or his dog." These complaints continued. In The Book of Days (1864), Robert Chambers wrote that wife sales, which English people saw as a small thing, made a big impression on people in other countries. They saw it as proof of England's "low civilisation."

Embarrassed by the practice, an 1853 legal book allowed English judges to say wife selling was a myth. It stated: "It is a vulgar error that a husband can get rid of his wife by selling her in the open market with a halter round her neck. Such an act on his part would be severely punished by the local magistrate." A legal guide from 1869 said that "publicly selling or buying a wife is clearly an indictable offence." It noted that many people had been charged and jailed for six months for doing so.

Another way of selling a wife was through a legal document called a deed of conveyance. This was less common than auctions at first. But it became more popular after the 1850s as public opinion turned against market sales. In 1881, Home Secretary William Harcourt was asked about an incident in Sheffield where a man sold his wife for beer. Harcourt replied that "no such practice as wife selling exists." However, as late as 1889, a member of the Salvation Army sold his wife for a shilling in Hucknall Torkard. He then led her by the halter to the buyer's house. This was the last known case where a halter was used. The most recent case of an English wife sale was reported in 1913. A woman in a Leeds police court said her husband had sold her to a co-worker for £1 (about £100 in today's money). The way she was sold was not recorded.

Images for kids

-

William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield (1705–1793), who thought wife selling was a trick.

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |