Women's club movement in the United States facts for kids

The women's club movement was an important social movement in the United States that began in the mid-1800s. It was a time when women came together to form groups, or clubs, to improve their communities and make a difference in public policy.

At first, many of these clubs were just for socializing and reading books. But soon, they became powerful forces for change. During a time called the Progressive Era (1896–1917), these clubs became a real movement. The first clubs were started by white, middle-class women. Later, a strong movement of clubs was also led by African-American women.

These clubs worked on many important issues. They fought to improve education, end child labor, and protect the environment. They also helped create kindergartens, public libraries, and special courts for young people. The clubs gave women, who had few political rights at the time, a way to make their voices heard and gain influence. Over time, as women gained more rights like the right to vote, the role of these clubs changed. While not as common today, many women's clubs still exist and continue to help their communities.

Contents

What Were Women's Clubs Like?

During the Progressive Era, many women believed they had a special duty to care for their communities, just as they cared for their homes. This idea was often called "municipal housekeeping," which means "city housekeeping." It was a way for women to explain why they should be involved in solving city problems. They argued that a healthy city was necessary for a healthy home.

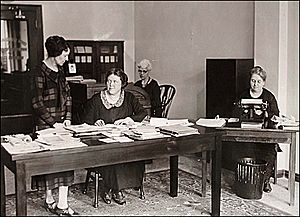

These clubs were also like "training schools" for women who wanted to be active in public life. They helped women learn how to organize, lead, and make a real impact.

Most clubs were organized with committees that focused on different tasks. Many groups even built their own clubhouses, which became important meeting places. Some of these historic buildings are still used by clubs today.

History of the Movement

Before the club movement, most groups for women were connected to churches or were support groups for men's organizations. Getting involved in church charities was one of the first ways women could work together outside the home.

As women started to have more free time, they formed their own clubs. At first, many were literary clubs, where women could read, share ideas, and make friends. These clubs helped women realize that their thoughts were valuable and that by working together, they could achieve great things.

Soon, the clubs shifted their focus from self-improvement to community improvement. They wanted to make their towns better places to live. In 1890, an organization called the General Federation of Women's Clubs (GFWC) was formed to unite many of these clubs. By 1914, it had over a million members. However, the GFWC and many white clubs did not allow African-American women to join. This led Black women to create their own powerful club movement.

During World War I, women's clubs were very active in supporting the war effort. They raised money, worked with the Red Cross, and sold war bonds to help fund the military.

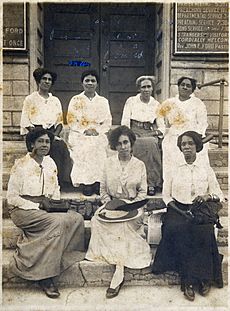

The African-American Club Movement

Even before the end of slavery, Black women organized groups to support their communities. One of the first was the Female Benevolent Society of St. Thomas, founded in Philadelphia in 1793. These early clubs often helped raise money for important causes, like anti-slavery newspapers.

After the 13th Amendment ended slavery in 1865, Black women continued to organize. They faced the same problems as white women but were often excluded from services and support. Because they were not allowed in white clubs, they formed their own. These clubs were a way for Black women to challenge negative stereotypes and prove their ability to lead and improve their communities.

Famous leaders like Ida B. Wells, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, and Mary Church Terrell helped organize these clubs. In 1896, they formed the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs (NACW). The NACW grew quickly, and by 1914, it had over 1,000 clubs. These clubs worked to improve education, health, and civil rights for African Americans.

A Slow Decline

By the 1960s, membership in women's clubs began to decrease. As women gained more rights and opportunities, including entering the workforce in greater numbers, they had less free time for club activities. Many of the tasks that clubs once handled, like providing social services, were taken over by city governments.

However, many clubs have adapted and continue to thrive in the 21st century. They still work to improve their communities, provide scholarships, and offer cultural events.

The Impact of Women's Clubs

Women's clubs had a huge impact on American society. They were responsible for many positive changes that we still see today.

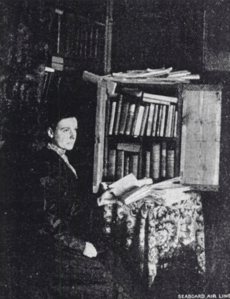

Education and Libraries

Women's clubs were champions of education. They pushed for women to be elected to school boards and helped create the first kindergartens in the United States.

One of their greatest achievements was establishing public libraries. It is estimated that women's clubs started 75 to 80 percent of the public libraries in the country. They would donate their own book collections, raise money to build library buildings, and even work as the first librarians. In areas without libraries, they created "traveling libraries" to bring books to people in rural communities.

Environment and Parks

Clubs were also pioneers in environmental protection. They worked to beautify their cities by creating parks and playgrounds. They also fought to protect natural resources.

Women's clubs played a key role in creating some of America's most famous national parks.

- In Colorado, clubs led the effort to create Mesa Verde National Park.

- In California, they helped save the giant Sequoia trees.

- In Florida, they campaigned to create what is now Everglades National Park.

- In 1916, the GFWC supported the creation of the National Park Service.

Health and Safety

Clubwomen worked to make their communities healthier and safer. They pushed for cleaner cities, safer food, and pure drinking water. Some clubs even inspected restaurants to make sure they were clean.

They also helped establish hospitals and clinics. In Seattle, a club member founded what is now the Seattle Children's Hospital.

Important Reforms

Fair Treatment for Children

Women's clubs were very concerned about the welfare of children. They fought against child labor and worked to make sure children stayed in school.

They also helped create the first juvenile courts. Before these courts, children who broke the law were treated like adult criminals. Clubwomen in Chicago successfully argued that children needed a separate court system that would focus on helping them. This idea spread across the country.

Women's Right to Vote

Women's clubs were a major force in the fight for women's suffrage, or the right to vote. They hosted speeches, organized rallies, and educated the public about why women deserved a voice in government.

Both Black and white women's clubs fought for suffrage. African-American clubs, like the NACW, also fought for the voting rights of Black men, which were often denied. The hard work of these clubs helped lead to the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, which gave women the right to vote.

See also

- List of women's clubs

- Feminism in the United States

- Gentlemen's clubs

- Women-only space

- Woman's Christian Temperance Union

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |