Everglades facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Everglades |

|

|---|---|

The most famous part of the Everglades is its sawgrass prairies.

|

|

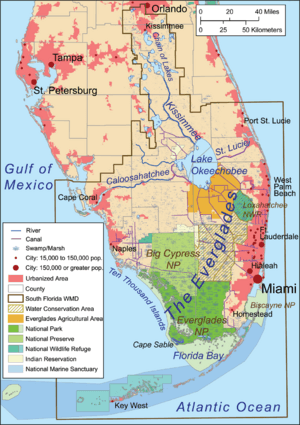

Where the Everglades are located in southern Florida

|

|

| Location | Florida, United States |

| Coordinates | 26°00′N 80°42′W / 26.0°N 80.7°W |

| Area | 7,800 square miles (20,000 km2) |

| Geology | Wetland |

The Everglades is a special natural region in southern Florida. It's mostly made of grassy wetlands and is part of a huge area where water flows. This amazing system starts near Orlando with the Kissimmee River. This river flows into a big, but shallow, lake called Lake Okeechobee.

During the wet season, water leaves Lake Okeechobee. It forms a very wide, slow-moving river that is about 60 miles (97 km) across and over 100 miles (160 km) long. This "river" flows south over a flat limestone area all the way to Florida Bay at the very end of the state. The Everglades has wild weather, from lots of floods in the wet season to dry spells in the dry season. For a long time, in the 1900s, the Everglades lost a lot of its natural areas and became damaged.

People have lived in southern Florida for about 15,000 years. Before Europeans arrived, the Calusa and Tequesta tribes lived here. When the Spanish came, these tribes slowly disappeared. Later, the Seminole people, who were mostly from the Creek tribe, moved into the Everglades. They were forced there during the Seminole Wars in the early 1800s. They learned to live in this unique place and were able to fight off the United States Army.

In 1848, people who wanted to build farms first suggested draining the Everglades. But no one started this work until 1882. Canals were built for many years in the early 1900s. This helped the economy in South Florida and led to more land being developed. In 1947, the government started the Central and Southern Florida Flood Control Project. This project built 1,400 miles (2,300 km) of canals, levees, and ways to control water.

The Miami metropolitan area grew a lot during this time, and water from the Everglades was sent to cities. Parts of the Everglades were turned into farmland, mainly for growing sugarcane. About half of the original Everglades has now been used for farms or cities.

After a time of fast growth and environmental damage, groups that care about nature started paying attention to the Everglades in the 1970s. Important international groups like UNESCO and the Ramsar Convention called the Everglades a "Wetland Area of Global Importance." Plans to build a huge airport near Everglades National Park were stopped. This happened after a study showed it would badly hurt the South Florida environment.

People became more aware of how special the Everglades is, and efforts to fix it began in the 1980s. One of the first steps was removing a canal that had straightened the Kissimmee River. However, concerns about new buildings and keeping the environment healthy are still important. The damage to the Everglades, including poor water quality in Lake Okeechobee, was linked to a lower quality of life in South Florida's cities. In 2000, the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan was approved by the government to help solve these problems. At the time, it was the most expensive and biggest environmental repair project ever planned. But putting the plan into action has faced some challenges.

What's in a Name?

The first time the Everglades was written about was on Spanish maps. The mapmakers hadn't actually seen the land. They called the unknown area between Florida's Gulf and Atlantic coasts "Laguna del Espíritu Santo," which means "Lake of the Holy Spirit." This area appeared on maps for many years before anyone explored it. In 1811, a writer named James Grant Forbes said that Native Americans described the southern parts as "impenetrable."

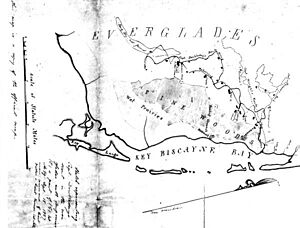

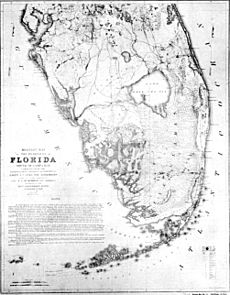

A British mapmaker, John William Gerard de Brahm, mapped the Florida coast in 1773. He called the area "River Glades." The name "Everglades" first showed up on a map in 1823, though it was sometimes spelled "Ever Glades" even as late as 1851. The Seminole people call it Pahokee, which means "Grassy Water." A U.S. military map from 1839 labeled the region "Pa-hai-okee."

A study in 2007 found that "the Glades" has become a special local region in Florida. It includes the inner and southernmost Gulf Coast areas of South Florida, which is mostly the Everglades itself. It is one of the least populated areas in the state.

How the Everglades Was Formed

The geology of South Florida, along with its warm, wet, subtropical and tropical climate, creates perfect conditions for a huge marshland. Layers of soft, water-holding limestone form water-filled rock and soil. These layers affect the weather, climate, and how water moves in South Florida.

The type of rock under the Everglades is due to Florida's long history. The land under Florida was once part of a supercontinent called Gondwana, near Africa. About 300 million years ago, North America joined with Africa, connecting Florida to North America. Later, about 180 million years ago, North America started to pull away from Gondwana. When Florida was part of Africa, it was above water. But during the cooler Jurassic Period, Florida became a shallow sea where layers of rock were laid down. For millions of years, most of Florida was a tropical sea floor. The peninsula has been covered by seawater at least seven times since its bedrock formed.

Limestone and Water Storage

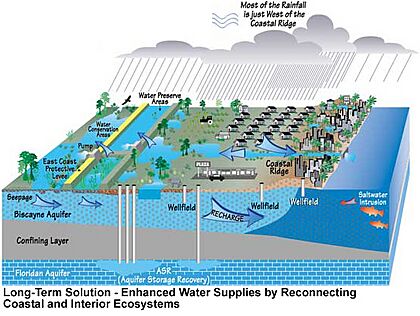

As sea levels changed over millions of years, many layers of calcium carbonate (like chalk), sand, and shells were pressed together. This created the soft limestone formations that developed between 25 million and 70 million years ago. These formations created the Floridan Aquifer, which is the main source of fresh water for northern Florida. However, this aquifer is deep under thousands of feet of solid rock from Lake Okeechobee to the southern tip of Florida.

Five types of rock make up the surface of southern Florida. The Tamiami Formation is a thick layer of soft, light-colored sand and quartz pockets. It is named after the Tamiami Trail road and lies under the southern Everglades. Another formation, the Caloosahatchee Formation, is less soft and is made of sandy shell and clay.

The Miami Limestone and the Fort Thompson Formation are the most important rock types for the Everglades. The Miami Limestone is made of tiny, egg-shaped bits of calcium carbonate called ooids. This rock is very porous, meaning it has many tiny holes. It stores water during the dry season in the Everglades. Its makeup also affects the plants and animals that live there. The Miami Oolite part of this limestone also stops water from flowing straight from the Everglades to the ocean.

The cities of Miami, Fort Lauderdale, and West Palm Beach are built on a slightly higher area along Florida's eastern coast. This area, called the Eastern Coastal Ridge, formed when waves pressed ooids together. On the western side of the Big Cypress Swamp, there's another slight rise called the Immokolee Ridge. These higher areas on both sides of the Everglades create a basin, which makes water from Lake Okeechobee flow slowly southwest.

Underneath the Miami Limestone and Fort Thompson limestone is the Biscayne Aquifer. This is a shallow underground water source that provides fresh water for the Miami area. Rain and stored water from the Everglades directly refill this aquifer.

About 17,000 years ago, sea levels rose. This slowed down the water flowing from Lake Okeechobee and created the huge marshland we now call the Everglades. The slow water flow also led to almost 18 feet (5.5 m) of peat building up in the area. This peat shows that widespread flooding had been happening for about 5,000 years.

How Water Flows (Hydrology)

The Everglades is always flooded because of many rivers in central Florida, like the Kissimmee, Caloosahatchee, and Miami Rivers. The Kissimmee River flows into Lake Okeechobee, which is a huge but shallow lake. In the Everglades basin, peat soil builds up where the land is flooded all year. Calcium deposits are left behind when flooding is shorter.

Long ago, the area from Orlando to the tip of Florida was one big water system. When Lake Okeechobee and the Kissimmee River floodplain got too full from rain, the water would spill over. It flowed southwest into Florida Bay. Before cities and farms were built, the Everglades started at the southern edge of Lake Okeechobee. It flowed for about 100 miles (160 km) and emptied into the Gulf of Mexico.

The limestone ground is wide and slightly tilted, not like a narrow, deep river channel. The land drops only about 2 inches (5.1 cm) for every mile from Lake Okeechobee to Florida Bay. This creates a river that is almost 60-mile (97 km) wide and moves very slowly, about half a mile (0.8 km) a day. This slow, wide flow of shallow water is called sheetflow. It's why the Everglades is nicknamed the "River of Grass." Water leaving Lake Okeechobee can take months or even years to reach Florida Bay. The sheetflow moves so slowly that water is often stored in the porous limestone from one wet season to the next. This constant movement of water has shaped the land and every part of the South Florida environment for about 5,000 years. The way water moves decides what plants grow and how animals live and find food.

Everglades Weather

South Florida and the Everglades have a climate that is between subtropical and tropical climates. This means there are two main seasons: a "dry season" (winter) from November to April, and a "wet season" (summer) from May to October. About 70% of the yearly rain in South Florida falls during the wet season. This often comes as short but heavy tropical thunderstorms. The dry season has little rain, and the air is often less humid. The dry season can be tough, sometimes leading to wildfires and water restrictions.

Temperatures in South Florida and the Everglades don't change much throughout the year. The average monthly temperature is around 65 °F (18 °C) in January and 83 °F (28 °C) in July. High temperatures in the hot, wet summer usually go above 90 °F (32 °C) inland. Coastal areas are cooler due to winds from the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean. In the dry winter, high temperatures average from 70 to 79 °F (21 to 26 °C). Frost and freezing temperatures are rare. Yearly rainfall is about 62 inches (160 cm) on average.

Unlike other wetlands, the Everglades gets most of its water from the atmosphere. Evapotranspiration—which is water evaporating from the ground and plants—is how water leaves the region. This process is linked to thunderstorms. In a normal year, about 40 inches (100 cm) of water can leave this way. During droughts, it can be over 50 inches (130 cm), which is more than the rainfall. As water evaporates, it is carried by wind to other areas of the Everglades. Evapotranspiration is responsible for about 70–90% of the water in undeveloped wetland areas of the Everglades.

Rain during the wet season mostly comes from thunderstorms and winds from a high-pressure area over the Atlantic. Strong daytime heat makes warm, moist air rise, causing the afternoon thunderstorms common in tropical climates. The wet season gets the most rain in August and September when tropical storms and low-pressure systems add to daily rainfall. Sometimes, tropical storms can become strong hurricanes. These can cause a lot of damage when they hit South Florida. On average, there is one tropical storm a year and a major hurricane about once every ten years. Strong winds from these storms spread plant seeds and help mangrove forests and coral reefs grow back. Big changes in rainfall are normal for South Florida's climate. Droughts, floods, and tropical storms are all part of the natural water system in the Everglades.

| Climate data for 36 mi WNW Miami, Miami-Dade County, Florida (1981 – 2010 averages). | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 76.7 (24.8) |

78.9 (26.1) |

81.1 (27.3) |

84.9 (29.4) |

88.6 (31.4) |

90.8 (32.7) |

91.9 (33.3) |

92.0 (33.3) |

90.4 (32.4) |

87.1 (30.6) |

82.1 (27.8) |

78.4 (25.8) |

85.3 (29.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 66.5 (19.2) |

68.6 (20.3) |

70.8 (21.6) |

74.0 (23.3) |

78.2 (25.7) |

82.0 (27.8) |

83.5 (28.6) |

83.9 (28.8) |

82.8 (28.2) |

79.5 (26.4) |

73.8 (23.2) |

69.0 (20.6) |

76.1 (24.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 56.2 (13.4) |

58.3 (14.6) |

60.5 (15.8) |

63.1 (17.3) |

67.7 (19.8) |

73.1 (22.8) |

75.1 (23.9) |

75.8 (24.3) |

75.3 (24.1) |

71.8 (22.1) |

65.4 (18.6) |

59.5 (15.3) |

66.9 (19.4) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.62 (41) |

2.03 (52) |

2.75 (70) |

2.56 (65) |

4.45 (113) |

8.70 (221) |

7.11 (181) |

7.42 (188) |

7.01 (178) |

4.02 (102) |

2.08 (53) |

1.38 (35) |

51.13 (1,299) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74.6 | 73.0 | 70.7 | 68.3 | 70.7 | 75.3 | 74.7 | 76.2 | 77.6 | 76.6 | 75.6 | 75.4 | 74.1 |

| Source: PRISM Climate Group | |||||||||||||

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Dew Point °F | 58.2 | 59.6 | 60.8 | 62.9 | 67.9 | 73.4 | 74.6 | 75.6 | 75.1 | 71.5 | 65.6 | 60.9 | 67.2 |

| Average Dew Point °C | 14.6 | 15.3 | 16.0 | 17.2 | 19.9 | 23.0 | 23.7 | 24.2 | 23.9 | 21.9 | 18.7 | 16.1 | 19.6 |

|

Source = PRISM Climate Group

|

|||||||||||||

| Climate data for Royal Palm Ranger Station, Florida, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1949–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 92 (33) |

97 (36) |

101 (38) |

102 (39) |

107 (42) |

104 (40) |

102 (39) |

103 (39) |

105 (41) |

106 (41) |

99 (37) |

95 (35) |

107 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 86.8 (30.4) |

88.4 (31.3) |

91.2 (32.9) |

93.3 (34.1) |

95.9 (35.5) |

97.1 (36.2) |

97.3 (36.3) |

97.3 (36.3) |

96.8 (36.0) |

94.7 (34.8) |

90.1 (32.3) |

87.5 (30.8) |

99.4 (37.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 78.0 (25.6) |

80.9 (27.2) |

83.3 (28.5) |

86.4 (30.2) |

89.4 (31.9) |

91.1 (32.8) |

92.5 (33.6) |

92.6 (33.7) |

91.3 (32.9) |

88.0 (31.1) |

83.2 (28.4) |

80.0 (26.7) |

86.4 (30.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 66.6 (19.2) |

68.7 (20.4) |

70.7 (21.5) |

74.2 (23.4) |

78.0 (25.6) |

81.6 (27.6) |

83.0 (28.3) |

83.5 (28.6) |

82.8 (28.2) |

79.4 (26.3) |

73.5 (23.1) |

69.3 (20.7) |

75.9 (24.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 55.1 (12.8) |

56.5 (13.6) |

58.0 (14.4) |

62.0 (16.7) |

66.6 (19.2) |

72.0 (22.2) |

73.5 (23.1) |

74.3 (23.5) |

74.2 (23.4) |

70.9 (21.6) |

63.8 (17.7) |

58.6 (14.8) |

65.5 (18.6) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 38.9 (3.8) |

41.7 (5.4) |

43.7 (6.5) |

50.3 (10.2) |

58.0 (14.4) |

67.8 (19.9) |

70.3 (21.3) |

71.0 (21.7) |

70.8 (21.6) |

61.3 (16.3) |

52.1 (11.2) |

44.5 (6.9) |

35.8 (2.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 24 (−4) |

29 (−2) |

31 (−1) |

37 (3) |

49 (9) |

50 (10) |

66 (19) |

66 (19) |

64 (18) |

49 (9) |

31 (−1) |

27 (−3) |

24 (−4) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.70 (43) |

1.82 (46) |

1.93 (49) |

2.85 (72) |

5.84 (148) |

9.00 (229) |

6.82 (173) |

8.57 (218) |

9.01 (229) |

5.55 (141) |

2.39 (61) |

1.88 (48) |

57.36 (1,457) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.6 | 6.5 | 6.7 | 6.3 | 10.9 | 17.2 | 17.2 | 19.2 | 18.3 | 12.6 | 7.8 | 6.6 | 135.9 |

| Source: NOAA | |||||||||||||

How the Everglades Stays Alive

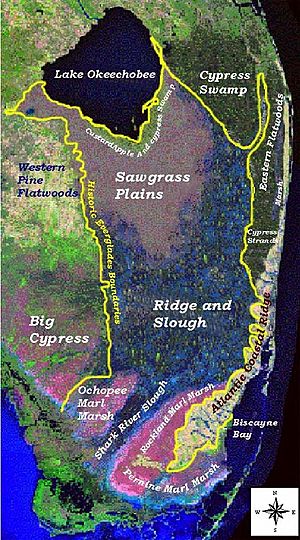

The Everglades is a complicated system of many different natural areas that depend on each other. Marjory Stoneman Douglas famously called it a "River of Grass" in 1947. But this name only describes one part of the system. Before people started draining it, the Everglades was a huge area of marshes and prairies, about 4,000 square miles (10,000 km2) in size. The lines between these different areas are often hard to see. These natural systems change, grow, shrink, die, or come back over years or decades. The type of rock, the climate, and how often fires happen all help create, keep, or change the Everglades' ecosystems.

The Role of Water

Water is the most important force in the Everglades. It shapes the land, the plants, and the animals in South Florida. About 21,000 years ago, when the last ice age ended, huge ice sheets melted and sea levels rose. This covered parts of Florida and made the water table (the level of water underground) rise. Fresh water soaked into the limestone under the Everglades, slowly wearing it away. This created springs and sinkholes. All this fresh water allowed new plants to grow. It also caused thunderstorms to form over the land as water evaporated.

As rain kept falling, the slightly acidic rainwater dissolved the limestone. As the limestone wore away, the underground water came to the surface. This created the massive wetland ecosystem. Even though the region looks flat, the wearing away of the limestone created small valleys and slightly higher areas. These differences are only a few inches, but in the flat South Florida landscape, these small changes affect how water flows and what types of plants can grow.

The Role of Rock

The bedrock, or limestone, under the Everglades affects the hydroperiod. This is how long an area in the region stays flooded each year. Longer hydroperiods happen in areas that were under seawater for longer when Florida's geology was forming. More water is held in the porous ooids and limestone than in older rocks that were above sea level for more time. If an area is flooded for ten months or more, it helps sawgrass grow. If it's flooded for six months or less, it helps periphyton grow. Periphyton is a mix of algae and tiny organisms.

There are only two main types of soil in the Everglades: peat and marl. Where there are longer hydroperiods, peat builds up over hundreds or thousands of years from decaying plants. Where periphyton grows, the soil becomes marl, which has more calcium.

Early attempts to farm near Lake Okeechobee worked at first. But the nutrients in the peat quickly ran out. When the water was drained in the 1920s, the peat started to break down quickly. This is called soil subsidence. Bacteria that usually break down dead sawgrass slowly underwater, without much oxygen, now had oxygen. This made them break down the peat much faster into carbon dioxide and water. Some settlers even burned the peat to clear the land. Some homes built on early farms had to be moved onto stilts because the peat disappeared. Other areas lost about 8 feet (2.4 m) of soil depth.

The Role of Fire

Fire is very important for keeping the Everglades healthy. Most fires are started by lightning during thunderstorms in the wet season. These fires usually only burn the surface. They help certain plants grow: sawgrass will burn above water, but its roots are safe underwater. Fire in the sawgrass marshes helps keep out larger bushes and trees. It also releases nutrients from dead plants more quickly than if they just decayed. In the wet season, dead plants and the tips of grasses and trees burn. But in the dry season, fire can burn deep into the organic peat, destroying root systems. Water and rain help stop fires from spreading too far. It takes about 225 years for one foot (0.30 m) of peat to form. But in some places, the peat is thinner than it should be for the Everglades' 5,000-year history. Scientists say fire is the reason for this. It's also why the Everglades muck is black. Layers of charcoal have been found in the peat, showing that the region had severe fires for years at a time in the past.

Everglades Ecosystems

Sawgrass Marshes and Sloughs

The Everglades has several different ecosystems, and the edges between them are often hard to see. The main feature of the Everglades is the sawgrass marsh. The famous mix of water and sawgrass in the shallow river, 100 miles (160 km) long and 60 miles (97 km) wide, that stretches from Lake Okeechobee to Florida Bay, is often called the "true Everglades." Before the first attempts to drain it in 1905, this sheetflow covered almost a third of the lower Florida peninsula. Sawgrass grows well in the slow-moving water. But it can die in unusually deep floods if its roots don't get enough oxygen. It's also very weak right after a fire. The sawgrass marsh is flooded for at least nine months, and sometimes longer. Where sawgrass grows very thickly, few animals or other plants live. However, alligators often build their nests in these spots. Where there is more space, periphyton grows. Periphyton provides food for insect larvae and amphibians, which are then eaten by birds, fish, and reptiles. It also takes in calcium from the water, adding to the calcium in the marl soil.

Sloughs, which are free-flowing channels of water, form between the sawgrass prairies. Sloughs are about 3 feet (0.91 m) deeper than sawgrass marshes. They can stay flooded for at least 11 months of the year, and sometimes for several years in a row. Water animals like turtles, alligators, snakes, and fish do well in sloughs. They usually eat small water creatures. Plants that grow underwater or float, like bladderwort (Utricularia), waterlily (Nymphaeaceae), and spatterdock (Nuphar lutea), also grow here. Important sloughs in the Everglades include the Shark River Slough (which flows to Florida Bay), Lostmans River Slough (next to The Big Cypress), and Taylor Slough in the eastern Everglades.

Wet prairies are slightly higher, like sawgrass marshes, but have more types of plants. The ground is covered in water for only three to seven months of the year. The water is usually shallow, about 4 inches (10 cm) deep. When flooded, the marl soil can support many different water plants. Solution holes, which are deep pits where the limestone has worn away, can stay flooded even when the prairies are dry. They support water creatures like crayfish and snails, and young amphibians, which are food for young wading birds. These areas are usually found between sloughs and sawgrass marshes.

Alligators have found a special way to live in wet prairies. They use their claws and snouts to dig low spots, creating ponds without plants. These ponds stay flooded during the dry season. Alligator holes are vital for water creatures, turtles, fish, small mammals, and birds to survive during long dry periods. The alligators then eat some of the animals that come to the hole.

Tropical Hardwood Hammocks

Small islands of trees that grow on land raised about 1 foot (0.30 m) to 3 feet (0.91 m) above sloughs and prairies are called tropical hardwood hammocks. They can be from one (4,000 m²) to ten acres (40,000 m²) in size. They can be found in freshwater sloughs, sawgrass prairies, or pineland areas. Hammocks are slightly higher on limestone areas that are a few inches above the surrounding peat. Or they might grow on land that hasn't been damaged by deep peat fires. Hardwood hammocks have a mix of subtropical and hardwood trees. These include Southern live oak (Quercus virginiana), gumbo limbo (Bursera simaruba), royal palm (Roystonea), and bustic (Dipholis salicifolia). These trees grow in very thick groups. Near the ground, sharp saw palmettos (Serenoa repens) grow, making hammocks very hard for people to walk through. But small mammals, reptiles, and amphibians find these islands a perfect home. Water in sloughs flows around the islands, creating moats. While some ecosystems need fire to stay healthy, hammocks can take decades or centuries to recover from a fire. The moats around the hammocks protect the trees. The trees' height is limited by things like frost, lightning, and wind. Most trees in hammocks don't grow taller than 55 feet (17 m).

Pineland Ecosystems

Some of the driest land in the Everglades is the pineland (also called pine rockland) ecosystem. It's in the highest part of the Everglades and has little to no flooding. However, some areas might have flooded solution holes or puddles for a few months. The most important tree in the pineland is the South Florida slash pine (Pinus elliottii). Pineland areas need fire to stay healthy. The pine trees have special ways to both help and resist fire. The sandy ground of the pine forest is covered with dry pine needles that burn easily. South Florida slash pines have thick bark that protects them from heat. Fire removes other plants on the forest floor that compete with the pines. It also opens pine cones to release seeds. If there isn't enough fire for a long time, pineland can turn into a hardwood hammock as larger trees take over the slash pines. The shrubs under the pine trees, like the fire-resistant saw palmetto (Serenoa repens), cabbage palm (Sabal palmetto), and West Indian lilac (Tetrazygia bicolor), can survive fires. The most diverse group of plants in the pine community are the herbs, with many different species. These plants have special parts like tubers that let them grow back quickly after being burned.

Before cities grew in South Florida, pine rocklands covered about 161,660 acres (654.2 km2) in Miami-Dade County. Inside Everglades National Park, 19,840 acres (80.3 km2) of pine forests are protected. But outside the park, only about 1,780 acres (7.2 km2) of pine areas remained by 1990. Not understanding the role of fire also led to the disappearance of pine forests. Natural fires were put out, and pine rocklands changed into hardwood hammocks. Now, controlled fires are set in Everglades National Park in pine rocklands every three to seven years.

Cypress Swamps

Cypress swamps are found throughout the Everglades. The largest one covers most of Collier County and is called "The Big Cypress." The name refers to its huge size, not the height of its trees. The swamp is at least 1,200 square miles (3,100 km2), but its water area can be over 2,400 square miles (6,200 km2). Most of The Big Cypress sits on bedrock covered by a thin layer of limestone. The limestone under the Big Cypress has quartz, which creates sandy soil. This soil supports different plants than other parts of the Everglades. The Big Cypress area gets about 55 inches (140 cm) of water on average during the wet season.

Even though The Big Cypress is the largest cypress swamp in South Florida, cypress swamps can also be found near the Atlantic coast, between Lake Okeechobee and the Eastern flatwoods, and in sawgrass marshes. Cypresses are trees that lose their needles in winter. They are specially made to live in flooded conditions. They have wide trunks at the bottom and roots that stick out of the water, called "knees." Bald cypress trees grow in groups, with the tallest and thickest trunks in the center, rooted in the deepest peat. As the peat gets thinner, cypresses grow smaller and thinner. This makes the small forest look like a dome from the outside. They also grow in long lines, slightly raised on a limestone ridge with sloughs on either side. Other hardwood trees can be found in cypress domes, like red maple, swamp bay, and pop ash. If cypresses are removed, the hardwoods take over, and the area becomes a mixed swamp forest.

Mangrove and Coastal Prairie

Eventually, water from Lake Okeechobee and The Big Cypress reaches the ocean. Mangrove trees are well-suited for the area where fresh and salt water mix, called brackish water. The Ten Thousand Islands area, which is almost entirely mangrove forests, covers nearly 200,000 acres (810 km2). In the wet season, fresh water flows into Florida Bay, and sawgrass starts to grow closer to the coast. In the dry season, especially during long droughts, salt water moves inland into the coastal prairie. This ecosystem acts as a buffer, protecting the freshwater marshes by soaking up seawater. Mangrove trees start to grow in freshwater areas when the salt water moves far enough inland.

There are three types of trees called mangroves: red (Rhizophora mangle), black (Avicennia germinans), and white (Laguncularia racemosa). They are all from different plant families. All of them grow in soil with little oxygen, can survive big changes in water levels, and can live in salt, brackish, or fresh water. All three mangrove species are very important for protecting the coastline during strong storms. Red mangroves have roots that spread out the farthest, trapping dirt that helps build coastlines after and between storms. All three types of trees absorb the power of waves and storm surges. Everglades mangroves also serve as safe places for young crustaceans and fish to grow. They are also nesting spots for birds. The region supports industries that catch Tortugas pink shrimp (Farfantepenaeus duorarum) and stone crab (Menippe mercenaria). Between 80% and 90% of the seafood caught for sale in Florida's salt waters are born or spend time near the Everglades.

Florida Bay Ecosystem

Much of the coast and the inner water areas are made of mangroves. There is no clear line between the coastal marshes and the bay. So, the ocean ecosystems in Florida Bay are considered part of the Everglades water system. They are connected to and affected by the Everglades as a whole. More than 800 square miles (2,100 km2) of Florida Bay is protected by Everglades National Park. This is the largest body of water within the park. There are about 100 small islands, called keys, in Florida Bay, and many of them are mangrove forests. The fresh water flowing into Florida Bay from the Everglades creates perfect conditions for huge beds of turtle grass and algae. These form the base of the food chain for animals in the bay. Sea turtles and manatees eat the grass. Small animals like worms, clams, and other mollusks eat the algae and tiny plankton. Female sea turtles return every year to lay eggs on the shore. Manatees spend the winter months in the warmer water of the bay. Sea grasses also help keep the seafloor stable and protect shorelines from being washed away by waves.

History of People in the Everglades

Native American Tribes

Humans first arrived in Florida about 15,000 years ago. These early people, called Paleo-Indians, probably followed large animals like giant sloths and saber-toothed cats. They found a dry landscape with plants and animals that could live in desert-like conditions. However, 6,500 years ago, the climate changed and brought more water. The large animals in Florida died out, and the Paleo-Indians slowly adapted. They became the Archaic peoples. They changed with the environment and made many tools from the resources they found. During the Late Archaic period, the climate became wetter again. Around 3000 BCE, rising water levels led to more people and cultural activity. Florida's Native Americans developed into three different but similar cultures, named after the bodies of water near where they lived: Okeechobee, Caloosahatchee, and Glades.

Calusa and Tequesta Tribes

From the Glades peoples, two main tribes grew in the area: the Calusa and the Tequesta. The Calusa were the largest and most powerful tribe in South Florida. They controlled many villages along Florida's west coast, around Lake Okeechobee, and on the Florida Keys. Most Calusa villages were at river mouths or on key islands. The Calusa were hunter-gatherers. They ate small animals, fish, turtles, alligators, shellfish, and various plants. Most of their tools were made of bone or teeth. They also used sharpened reeds for hunting or war. Calusa weapons included bows and arrows, atlatls, and spears. They used canoes for travel, often going through the Everglades, but they rarely lived there. They even canoed to Cuba.

When the Spanish first arrived, there were an estimated 4,000 to 7,000 Calusa. Their power and population dropped. By 1697, there were only about 1,000 left. In the early 1700s, the Calusa were attacked by the Yamasee from the north. They asked the Spanish for safety in Cuba, where almost 200 died from illness. Soon, they were moved again to the Florida Keys.

The Tequesta were the second most powerful tribe in South Florida. They lived in the southeastern part of the peninsula, in what is now Dade and Broward counties. Like the Calusa, Tequesta villages were usually at river mouths. Their main village was probably on the Miami River. Spanish accounts say that sailors feared the Tequesta, believing they killed shipwreck survivors. As more Europeans came to South Florida, Native Americans from the Keys and other areas started visiting Cuba more often. Spanish priests tried to set up missions in 1743. But they noted that the Tequesta were being attacked by a neighboring tribe. When only 30 Tequesta members were left, they were moved to Havana. By 1820, Native Americans in Florida were usually just called "Seminoles."

The Seminole People

After the Calusa and Tequesta tribes faded, Native Americans in southern Florida were called "Spanish Indians" in the 1740s. This was probably because they had friendlier ties with Spain. The Creek people moved into Florida. They took in what was left of earlier tribes and formed the Seminole, a new tribe. Also, free Black people and runaway slaves came to Florida. Spain had promised freedom and weapons to slaves if they became Catholic and loyal to Spain. These African Americans gradually formed communities near the Seminole, becoming known as the Black Seminoles. The two groups became allies.

In 1817, Andrew Jackson invaded Florida to help the U.S. take it over. This was called the First Seminole War. After Florida became a U.S. territory in 1821, conflicts between settlers and the Seminole grew. Settlers wanted more land. The Second Seminole War lasted from 1835 to 1842. After this war, the U.S. forced about 3,000 Seminole and 800 Black Seminole to move to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). Many others died in the war. Conflict started again in the Third Seminole War from 1855 to 1859. A few hundred Seminole fought off U.S. forces from the Everglades swamps. The U.S. finally decided to leave them alone, as they couldn't remove them even after this long and costly war.

By 1913, there were no more than 325 Seminole in the Everglades. They made a living by hunting and trading with white settlers. They also raised farm animals. The Seminole built their villages in hardwood hammocks or pinelands. Their diet included hominy, coontie roots, fish, turtles, deer, and small game. Their villages were not large because hammocks are small islands. Between the end of the last Seminole War and 1930, the people lived mostly separate from the main culture.

The building of the Tamiami Trail road, starting in 1928, changed their way of life. Some began working on local farms, ranches, and souvenir stands. Some who interacted more with European Americans started moving to reservations in the 1940s. These became their bases for organizing their government. They were officially recognized by the U.S. government in 1957 as the Seminole Tribe of Florida.

People who kept more traditional ways lived along the Tamiami Trail and often spoke the Mikasuki language. They were later recognized by the U.S. government in 1962 as the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida. As cities in South Florida grew, both groups became closely linked with the Everglades. They tried to keep their privacy while also being tourist attractions. They earned money by wrestling alligators and selling crafts. As of 2008, the Seminole Tribe of Florida had five reservations. The Miccosukee Tribe's lands were considered a sixth reservation. Both tribes have built casinos on some of their lands to earn money for their communities.

Early Exploration of the Everglades

The military's trips into southern Florida helped map a part of the country that was not well known. An expedition into the Everglades in 1840 provided the first written account for the public to read. The writer described the land they were crossing: "No country that I have ever heard of bears any resemblance to it; it seems like a vast sea filled with grass and green trees, and expressly intended as a retreat for the rascally Indian, from which the white man would never seek to drive them."

The land seemed to cause strong feelings, either wonder or dislike. During the Second Seminole War, an army doctor wrote, "It is in fact a most hideous region to live in, a perfect paradise for Indians, alligators, serpents, frogs, and every other kind of loathsome reptile."

A survey team led by railroad executive James Edmundson Ingraham explored the area in 1892. In 1897, explorer Hugh Willoughby spent eight days canoeing with a group from the mouth of the Harney River to the Miami River. He sent his notes to a newspaper. Willoughby described the water as healthy and clean, with many springs. He saw "10,000 alligators more or less" in Lake Okeechobee. The group saw thousands of birds near the Shark River, "killing hundreds, but they continued to return." Willoughby noted that most of the country had been explored and mapped, except for this part of Florida. He wrote that "(w)e have a tract of land one hundred and thirty miles long and seventy miles wide that is as much unknown to the white man as the heart of Africa."

Draining the Everglades

In the late 1800s, there was a national push for growth in the United States. This made people interested in draining the Everglades for farming. Historians say that from the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s, people didn't question removing wetlands. In fact, it was seen as the right thing to do. Draining the Everglades was first suggested as early as 1837. In 1842, Congress passed a law asking people with Everglades experience for their thoughts on draining it. Many officers who fought in the Seminole Wars liked the idea. In 1850, Congress passed a law that gave several states wetlands within their borders. The Swamp and Overflowed Lands Act made states responsible for paying to turn wetlands into farmland. Florida quickly formed a committee to get money for these efforts. But the Civil War and Reconstruction stopped progress until after 1877.

After the Civil War, a state agency called the Internal Improvement Fund (IIF) was in deep debt. Its job was to improve Florida's roads, canals, and rail lines. The IIF found a real estate developer from Pennsylvania named Hamilton Disston. He was interested in draining the land for farming. Disston bought 4,000,000 acres (16,000 km2) of land for $1 million in 1881. He started building canals near St. Cloud. At first, the canals seemed to lower water levels in the wetlands around the rivers. They did lower the underground water, but it became clear they weren't big enough for the wet season. Even though Disston's canals didn't drain well, his purchase boosted Florida's economy. It made news and attracted tourists and land buyers. Within four years, land values doubled, and the population grew a lot.

The IIF could invest in development projects because of Disston's purchase. An opportunity to improve transportation came when oil tycoon Henry Flagler started buying land and building rail lines along Florida's east coast. By 1893, he had built lines as far south as Palm Beach. Along the way, he built resort hotels, turning small towns into tourist spots. The land next to the rail lines was developed into citrus farms. By 1896, the rail line reached Biscayne Bay. Three months after the first train arrived, the people of Miami voted to make it a town. Miami became a top destination for very wealthy people after the Royal Palm Hotel opened.

During the 1904 election for governor, the strongest candidate was Napoleon Bonaparte Broward. He was a Democrat who supported draining the Everglades. He called the future of South Florida the "Empire of the Everglades." After he won the election, he started working to "drain that abominable pestilence-ridden swamp." He pushed the Florida government to create a group of commissioners to manage reclaiming flooded lands. In 1907, they set up the Everglades Drainage District. They began studying how to build the best canals and how to pay for them. Governor Broward ran for the U.S. Senate in 1908 but lost. He was paid by land developer Richard J. Bolles to travel the state and promote drainage. Broward was elected to the Senate in 1910 but died before he could take office. Land in the Everglades was being sold for $15 an acre a month after Broward died. Meanwhile, Henry Flagler kept building railway stations in towns as soon as they had enough people.

Growth of Cities

With the canals built, newly drained Everglades land was advertised across the United States. Land developers sold 20,000 lots in just a few months in 1912. Ads promised that within eight weeks of arriving, a farmer could be making a living. But for many, it took at least two months just to clear the land. Some tried burning off the sawgrass or other plants, only to find that the peat soil kept burning. Animals and tractors used for plowing got stuck in the mud and couldn't be used. When the mud dried, it turned into a fine black powder, causing dust storms. At first, crops grew quickly and lushly, but then they just as quickly wilted and died for no clear reason.

The growing population in towns near the Everglades hunted in the area. Raccoons and otters were hunted most for their skins. Hunting often went uncontrolled. On one trip, a hunter near Lake Okeechobee killed 250 alligators and 172 otters. Water birds were especially targeted for their feathers. Bird feathers were used in women's hats in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

In 1886, an estimated 5 million birds were killed for their feathers. The plumes, or aigrettes, as they were called in the hat-making business, sold for $32 an ounce in 1915—the same price as gold. Hat-making was a $17 million a year industry. This motivated plume hunters to watch nests of egrets and other colorful birds during nesting season. They would shoot the parent birds with small rifles and leave the chicks to starve. Plumes from Everglades wading birds could be found in Havana, New York City, London, and Paris. Hunters could collect plumes from a hundred birds on a good day.

Rum-runners used the Everglades as a hiding spot during Prohibition. It was so vast that there were never enough law enforcement officers to patrol it. The arrival of the railroad, and the discovery that adding small amounts of elements like copper helped crops grow without dying, soon led to a population boom. New towns like Moore Haven, Clewiston, and Belle Glade grew quickly, just like the crops. Sugarcane became the main crop grown in South Florida. Miami had a second real estate boom that made one developer in Coral Gables $150 million. Undeveloped land north of Miami sold for $30,600 an acre. In 1925, Miami newspapers published editions weighing over 7 pounds (3.2 kg), mostly from real estate ads. Land along the water was the most valuable. Mangrove trees were cut down and replaced with palm trees to make the view better. Acres of South Florida slash pine were cleared. Some pine was used for lumber, but most pine forests in Dade County were cleared for building.

Flood Control Efforts

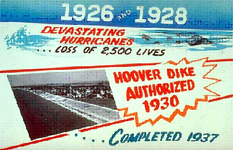

Two terrible hurricanes in 1926 and 1928 caused Lake Okeechobee's levees (walls) to break. Thousands of people died. The government then started focusing on controlling floods instead of just draining land. The Okeechobee Flood Control District was created in 1929, paid for by both state and federal money. President Herbert Hoover visited the towns hit by the 1928 hurricane. He ordered the Army Corps of Engineers to help the communities around the lake. Between 1930 and 1937, a dike 66 miles (106 km) long was built around the southern edge of the lake. Control of the Hoover Dike and the waters of Lake Okeechobee was given to the federal government. The U.S. set legal limits for the lake's water level, between 14 and 17 feet (4.3 and 5.2 m). A huge canal, 80 feet (24 m) wide and 6 feet (1.8 m) deep, was also built through the Caloosahatchee River. If the lake rose too high, the extra water would leave through this canal. More than $20 million was spent on the whole project. Sugarcane production greatly increased after the dike and canal were built. The populations of the small towns around the lake jumped from 3,000 to 9,000 after World War II.

The effects of the Hoover Dike were seen right away. A long drought happened in the 1930s. With the wall stopping water from leaving Lake Okeechobee and canals removing other water, the Everglades became very dry. Peat turned to dust. Salt ocean water got into Miami's wells. When the city brought in an expert to find out why, he discovered that the water in the Everglades was the area's groundwater—but here, it was on the surface. In 1939, a million acres (4,000 km²) of Everglades burned. Black clouds from the peat and sawgrass fires hung over Miami. Scientists who took soil samples before draining didn't realize that the organic peat and muck in the Everglades would shrink when it dried. Naturally occurring bacteria in Everglades peat and muck help with decomposition underwater, which is usually very slow. This is partly because there isn't much dissolved oxygen. When water levels got so low that peat and muck were at the surface, the bacteria got much more oxygen from the air. This made them break down the soil very quickly. In some places, homes had to be moved onto stilts, and 8 feet (2.4 m) of soil was lost.

Everglades National Park is Created

The idea of a national park for the Everglades was first suggested in 1928. A Miami land developer named Ernest F. Coe started the Everglades Tropical National Park Association. It gained enough support to be declared a national park by Congress in 1934. It took another 13 years for it to be officially opened on December 6, 1947. One month before the park opened, a former editor from The Miami Herald and writer named Marjory Stoneman Douglas released her first book, The Everglades: River of Grass. After studying the region for five years, she described the history and nature of South Florida in great detail. She called the Everglades a river instead of a still swamp. The last chapter, "The Eleventh Hour," warned that the Everglades was dying, but that it could be saved.

Central and Southern Florida Flood Control Project (C&SF)

The same year the park was opened, two hurricanes and the wet season brought 100 inches (250 cm) of rain to South Florida. There were no human deaths, but farms lost about $59 million. In 1948, Congress approved the Central and Southern Florida Project for Flood Control and Other Purposes (C&SF). This project divided the Everglades into different areas. In the northern Everglades were Water Conservation Areas (WCAs), and the Everglades Agricultural Area (EAA) south of Lake Okeechobee. In the southern Everglades was Everglades National Park. Levees and pumping stations were built around each WCA. They released water in dry times or removed it and pumped it to the ocean during floods. The WCAs took up about 37% of the original Everglades. The C&SF built over 1,000 miles (1,600 km) of canals and hundreds of pumping stations and levees within 30 years. During the 1950s and 1960s, the Miami area grew four times faster than the rest of the nation. Between 1940 and 1965, 6 million people moved to South Florida: 1,000 people moved to Miami every week. Developed areas quadrupled between the mid-1950s and late 1960s. Much of the water taken from the Everglades was sent to these new areas.

Everglades Agricultural Area (EAA)

The C&SF set aside 470,000 acres (1,900 km2) for the Everglades Agricultural Area (EAA). This was 27% of the Everglades before development. In the late 1920s, farming tests showed that adding large amounts of manganese sulfate to Everglades muck helped grow profitable vegetables. The main crop in the EAA is sugarcane, but sod, beans, lettuce, celery, and rice are also grown. Fields in the EAA are usually 40 acres (160,000 m2) and are bordered by canals on two sides. These canals connect to larger canals where water is pumped in or out depending on what the crops need. The fertilizers used on vegetables, along with high amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus from decaying soil needed for sugarcane, were pumped into WCAs south of the EAA. These chemicals allowed new, non-native plants to grow in the Everglades. One of the key features of the natural Everglades is that it can support itself in a low-nutrient environment. Adding fertilizers started to change the plant life in the region.

Stopping the Jetport Plan

A big change for development in the Everglades happened in the late 1960s. There was a plan for a huge airport because Miami International Airport was too small. The new jetport was planned to be bigger than several major airports combined. Its location was 6 miles (9.7 km) north of Everglades National Park. The first sentence of the U.S. Department of Interior study on the environmental impact of the jetport said, "Development of the proposed jetport and its attendant facilities... will inexorably destroy the south Florida ecosystem and thus the Everglades National Park." When studies showed the jetport would create 4,000,000 US gallons (15,000,000 L) of raw sewage a day and 10,000 short tons (9,100 t) of jet engine pollution a year, the project faced strong opposition. The New York Times called it a "blueprint for disaster." Wisconsin senator Gaylord Nelson wrote to President Richard Nixon saying he was against it: "It is a test of whether or not we are really committed in this country to protecting our environment." Governor Claude Kirk also stopped supporting the project. Marjory Stoneman Douglas, at 79 years old, was convinced to go on tour and give hundreds of speeches against it. Instead, Nixon suggested creating Big Cypress National Preserve. Although only one runway was built, the remains of the Everglades Jetport later opened as the Dade-Collier Training and Transition Airport. It is sometimes used for aviation training.

Restoring the Everglades

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) said in 2020 that the Everglades National Park's health was "Critical." They found that things were "deteriorating" with a "very high threat" to the ecosystem's overall health. Sadly, some natural features that have been lost cannot be brought back exactly as they were, because they took decades or centuries to form. The remaining natural features are very important to protect. They are vital for Florida and have unique qualities not found anywhere else in the world.

Major reasons for this decline include water quality (pollution from nutrients), water quantity (less water flow), and how water is spread and timed. Other threats are invasive species, climate change (like rising sea levels), ocean acidification, and hurricanes. Other big problems for Everglades restoration are slow action in planning and laws. Restoration projects in other parts of Florida (like the Tamiami Trail Next Steps, and water storage south of Lake Okeechobee) have not received enough attention. But these are essential to stop further loss.

While some Everglades Restoration projects have been finished, important plans are still incomplete. Also, earlier plans for the current projects overestimated how much they would help water flow and the environment. Restoration projects planned to be done by 2027, which are supposed to fix these problems, don't have enough funding on time.

Recent changes in park rules have been praised for showing good improvement. These include better ways to manage visitor activities, efforts to deal with invasive species, better controlled fires, and more funding for park projects. However, even though the park itself is working harder, support from local, state, and federal governments has not matched the critical need for conservation.

Kissimmee River Restoration

The last big construction project of the Central and Southern Florida Flood Control Project was straightening the Kissimmee River. This was a winding, 90-mile (140 km)-long river that was drained to make way for grazing land and farms. The C&SF started building the C-38 canal in 1962, and the effects were seen almost immediately. Waterfowl, wading birds, and fish disappeared. This made conservationists and sport fishers demand that the region be restored before the canal was finished in 1971. In general, C&SF projects had been criticized for being temporary fixes that didn't think about future problems. They cost billions of dollars with no end in sight. After Governor Bob Graham started the Save Our Everglades campaign in 1983, the first part of the canal was filled back in 1986. Graham announced that by 2000, the Everglades would be restored as close as possible to its natural state before it was drained. The Kissimmee River Restoration project was approved by Congress in 1992. It is estimated to cost $578 million to convert only 22 miles (35 km) of the canal. The whole project was supposed to be done by 2011. But as of 2017, the project is "more than halfway complete" and the new completion date is 2020.

Improving Water Quality

More environmental problems came up when a huge algal bloom appeared in one-fifth of Lake Okeechobee in 1986. In the same year, cattails were found taking over sawgrass marshes in Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge. Scientists found that phosphorus, used as a fertilizer in the EAA, was washed into canals and pumped back into the lake. When the lake drained, the phosphorus entered the water in the marshes, changing the nutrient levels. It stopped periphyton from forming marl, which is one of the two types of soil in the Everglades. The phosphorus allowed cattails to spread quickly. The cattails grew in thick mats—too dense for birds or alligators to nest in. It also used up oxygen in the peat, helped algae grow, and stopped native small water creatures from growing at the bottom of the food chain.

At the same time, mercury was found in local fish at such high levels that warnings were put up for fishermen not to eat them. A Florida panther was found dead with enough mercury to kill a human. Scientists found that power plants and incinerators burning fossil fuels were releasing mercury into the air. It then fell as rain or dust during droughts. The natural bacteria in the Everglades that reduce sulfur were changing the mercury into methylmercury. This mercury then built up in animals through the food chain, a process called Bioaccumulation. Stricter rules on emissions helped lower mercury coming from power plants and incinerators. This, in turn, lowered mercury levels found in animals, though it continues to be a concern.

The Everglades Forever Act, started by Governor Lawton Chiles in 1994, was an attempt to make laws to lower phosphorus in Everglades waterways. The act put the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD) and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) in charge of testing and enforcing low phosphorus levels: 10 parts per billion (ppb) (down from 500 ppb in the 1980s). The SFWMD built Stormwater Treatment Areas (STAs) near sugarcane fields. Water leaving the EAA flows into ponds lined with lime rock and layers of peat and calcareous periphyton. Testing has shown this method works better than expected, bringing levels from 80 ppb to 10 ppb.

Dealing with Invasive Species

As a place for trade and travel between the U.S., the Caribbean, and South America, South Florida is very open to invasive species. These are plants and animals that adapt very well to the Everglades. They reproduce faster and grow larger than they would in their native homes. About 26% of all fish, reptiles, birds, and mammals in South Florida are not native—more than anywhere else in the U.S. The region also has one of the highest numbers of non-native plant species in the world. Controlling invasive species in 1,700,000 acres (6,900 km²) of affected land in South Florida costs authorities about $500 million a year.

The Everglades has 1,392 non-native plant species that are actively reproducing. This is more than the 1,301 species that are native to South Florida. The melaleuca tree (Melaleuca quinquenervia) uses more water than other trees. Melaleucas grow taller and thicker in the Everglades than in their native Australia. This makes them unsuitable as nesting areas for birds with wide wingspans. They also crowd out native plants. More than $2 million has been spent trying to keep them out of Everglades National Park.

Brazilian pepper, or Florida holly (Schinus terebinthifolius), has also caused a lot of damage in the Everglades. It spreads quickly and crowds out native plants. It also creates bad environments for native animals. It is very hard to get rid of and is easily spread by birds, which eat its small red berries. The Brazilian pepper problem is not only in the Everglades. Neither is the water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes), which is a widespread problem in Florida's waterways. It is a major threat to native species and is difficult and expensive to remove. The Old World climbing fern (Lygodium microphyllum) might be causing the most harm to restoration efforts. It covers areas very thickly, making it impossible for animals to pass through. It also climbs up trees and creates "fire ladders," allowing parts of the trees to burn that would otherwise be safe.

Many pets have escaped or been released into the Everglades from nearby cities. Some find the conditions very good and have started their own populations. They compete for food and space with native animals. Many tropical fish have been released. Blue tilapias (Oreochromis aureus) damage shallow waterways by building large nests and eating water plants that protect young native fish.

Native to southern Asia, the Burmese python (Python molurus bivittatus) is a relatively new invasive species in the Everglades. This snake can grow up to 20 feet (6.1 m) long. They compete with alligators for the top of the food chain. Florida wildlife officials believe that escaped pythons have started reproducing in an environment that suits them well. In 2017, the South Florida Water Management District started the Python Elimination program. They hoped to encourage the public to help remove the snakes by offering a cash reward for each foot of python caught. They also offered extra pay and $200 for each active nest found. In Everglades National Park alone, agents removed more than 2,000 Burmese pythons from the park as of 2017. Federal authorities banned four species of non-native snakes, including the Burmese python, in 2012. Pythons are thought to be responsible for big drops in the populations of some mammals in the park. A 2015 study found that 77% of marsh rabbits that were eaten were killed by pythons. These kinds of relationships are believed to be a reason for the decline of native predators like the Florida Panther, which has fewer than 500 individuals left in the wild.

The Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP)

Even though scientists made progress in lowering mercury and phosphorus levels in the water, the natural environment of South Florida continued to get worse in the 1990s. Life in nearby cities also showed this decline. To fix the problems in the Miami area, Governor Lawton Chiles asked for a report on how to keep the area healthy for the long term. In 1995, Chiles published the report's findings. It connected the damage to the Everglades ecosystems to a lower quality of life in cities. The report pointed out past environmental mistakes that led the state to a point where it had to make a decision. The report predicted that if nothing was done to improve the South Florida ecosystem, it would get even worse. This would harm local tourism, costing 12,000 jobs and $200 million each year. Commercial fishing would lose 3,300 jobs and $52 million annually. Cities had grown too big to support themselves. Crowded cities faced problems like high crime rates, traffic jams, very crowded schools, and overworked public services. The report noted that water shortages were strange, given the 53 inches (130 cm) of rain the region received every year.

In 1999, a review of the C&SF project was given to Congress. This seven-year report, called the "Restudy," listed signs of harm to the ecosystem. These included a 50% reduction in the original Everglades, less water storage, bad timing of water releases from canals and pumping stations, an 85% to 90% decrease in wading bird populations over the past 50 years, and a decline in commercial fishing. Bodies of water like Lake Okeechobee, the Caloosahatchee River, St. Lucie estuary, Lake Worth Lagoon, Biscayne Bay, Florida Bay, and the Everglades showed big changes in water levels, very high saltiness, and huge changes in ocean and freshwater ecosystems. The Restudy noted that the overall decline in water quality over the past 50 years was due to the loss of wetlands, which naturally filter polluted water. It predicted that without action, the entire South Florida ecosystem would get worse. Water shortages would become common, and some cities would have yearly water restrictions.

The Restudy came with a plan to stop the environmental decline. This proposal was to be the most expensive and biggest ecological repair project in history. The Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP) suggested more than 60 construction projects over 30 years. These projects would store water that was being flushed into the ocean in reservoirs, underground water sources, and old quarries. They would add more Stormwater Treatment Areas to filter water flowing into the lower Everglades. They would also control water released from pumping stations into local waterways and improve water released to Everglades National Park and Water Conservation Areas. The plan also aimed to remove barriers to sheetflow by raising the Tamiami Trail road and destroying the Miami Canal. It also planned to reuse wastewater for cities. The estimated cost for the entire plan was $7.8 billion. In a show of cooperation from both political parties, CERP was voted through Congress with a huge majority. President Bill Clinton signed it on December 11, 2000.

Since it was signed, the State of Florida reports that it has spent more than $2 billion on the various projects. More than 36,000 acres (150 km2) of Stormwater Treatment Areas have been built to filter 2,500 short tons (2,300 t) of phosphorus from Everglades waters. An STA covering 17,000 acres (69 km2) was built in 2004, making it the largest man-made wetland in the world. Fifty-five percent of the land needed for restoration has been bought by the State of Florida, totaling 210,167 acres (850.52 km2). A plan to speed up the construction and funding of projects was put in place, called "Acceler8." This plan started six of eight large construction projects, including three big reservoirs. However, federal funds have not come as expected. CERP was signed when the U.S. government had extra money, but since then, budget deficits have returned. Also, two of CERP's main supporters in Congress retired.

The U.S. National Research Council has published reports every two years reviewing CERP's progress. The fourth report, released in 2012, found that little progress had been made in restoring the main part of the Everglades ecosystem. Instead, most construction so far has happened around its edges. The report noted that to stop the ongoing decline of the ecosystem, it will be necessary to speed up restoration projects that focus on the central Everglades. It also said that both the quality and quantity of water in the ecosystem need to be improved. To better understand what might happen if progress stays slow, the report looked at the current state of ten Everglades ecosystem features. These included phosphorus levels, peat depth, and populations of snail kites, which are endangered birds of prey in South Florida. Most features received grades from C (damaged) to D (very damaged), but the snail kite received an F (almost irreversible damage). The report also looked at what might happen to each ecosystem feature under three different restoration plans: better water quality, better water flow, and improvements to both. This helped show how urgent restoration actions are to help many ecosystem features and what it would cost to do nothing. Overall, the report concluded that significant progress is needed soon to fix both water quality and water flow in the central Everglades. This is needed to stop the ongoing damage before it's too late.

The Future of the Everglades

In 2008, the State of Florida agreed to buy U.S. Sugar and all its factories for about $1.7 billion. Florida officials said they planned to let U.S. Sugar operate for six more years before closing it down and letting its employees go. The area, which includes 187,000 acres (760 km2) of land, would then be restored. Water flow from Lake Okeechobee would be brought back. In November 2008, the agreement was changed to offer $1.34 billion, allowing sugar mills in Clewiston to keep producing sugar. Critics of the new plan say it means sugarcane will be grown in the Everglades for at least another ten years. More research is being done to manage sugarcane production in the Everglades to reduce phosphorus runoff.

Everglades restoration received $96 million from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. Because of this money, the Army Corps of Engineers started building a mile-long (1.6 km) bridge in December 2009. This bridge will replace part of the Tamiami Trail, a road that borders Everglades National Park to the north and has blocked water from reaching the southern Everglades. The next month, work began to rebuild the C-111 canal, east of the park. This canal historically diverted water into Florida Bay. Governor Charlie Crist announced in the same month that $50 million of state funds would be set aside for Everglades restoration. In May 2010, it was suggested that 5.5 miles (8.9 km) of bridges be added to the Tamiami Trail.

Plane Crashes in the Everglades

At least three airplanes have crashed in the Everglades:

- Northwest Airlines Flight 705, on February 12, 1963, where all 43 passengers and crew died.

- On December 29, 1972, Eastern Air Lines Flight 401 crashed, causing 101 deaths. There were 75 survivors. The crash was due to pilot error.

- On May 11, 1996, ValuJet Flight 592 crashed, killing all 110 passengers and crew. The cause was a fire in the cargo area during the flight.

See also

In Spanish: Everglades para niños

In Spanish: Everglades para niños

Images for kids

-

Limestone formations in South Florida. Source: U.S. Geological Survey

-

Hurricane Charley in 2004 moving ashore on South Florida's Gulf of Mexico coast

-

Uneven limestone formations in an Everglades sawgrass prairie

-

A clump of mangroves in the distance, Florida Bay at Flamingo

-

Map of the Everglades in 1856: Military action during the Seminole Wars improved understanding of the features of the Everglades.

-

President Harry Truman dedicating Everglades National Park on December 6, 1947

-

Warnings are placed in Everglades National Park to dissuade people from eating fish due to high mercury content. This warning explicitly mentions bass.

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |