Tequesta facts for kids

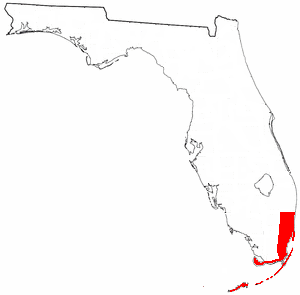

Approximate territory of the Tequesta

in the 16th century |

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Present-day South Florida (from 3rd century BCE to mid-18th century) |

The Tequesta people were a Native American tribe. When Europeans first arrived, the Tequesta lived along the southeastern Atlantic coast of Florida. They did not often meet Europeans. By the mid-1700s, most of the Tequesta people had moved away.

Contents

Where the Tequesta Lived

The Tequesta tribe lived in what is now southeastern Florida. They had lived in this area for about 2,000 years, starting around 300 BCE. By the 1800s, most Tequesta had died from fighting, slavery, and diseases. Only a few Tequesta were left when Spanish Florida became part of British territory.

The Tequesta lived around Biscayne Bay. This area is now Miami-Dade County. They also lived further north in Broward County, near Pompano Beach. Their land might have included the northern part of Broward County and the southern part of Palm Beach County. Sometimes, they also lived in the Florida Keys. They may have had a village on Cape Sable, at the very tip of Florida, in the 1500s.

Their main town was called "Tequesta" by the Spanish. It was on the north side of the Miami River. People had lived in this spot for at least 2,000 years. The Tequesta built their towns and camps near river mouths, ocean inlets, and on barrier islands.

The Tequesta were somewhat controlled by the Calusa tribe. The Calusa lived on the southwest coast of Florida and had more people. The Tequesta were good friends with their neighbors to the north, the Jaega tribe. When Europeans first arrived, there were likely between 800 and 10,000 Tequesta people. The Calusa numbered between 2,000 and 20,000. Sometimes, both tribes might have used the Florida Keys. Even though Spanish records mention a Tequesta village on Cape Sable, archaeologists find more Calusa items there.

Old maps show the Tequesta's land. A map from 1630 by Hessel Gerritsz called the Florida peninsula "Tegesta." An 18th-century map labeled the Biscayne Bay area "Tekesta." A map from 1794 by Bernard Romans also called this area "Tegesta."

Language and History

| Tequesta | |

|---|---|

| Region | Florida |

| Extinct | 18th century |

| Language family |

unclassified (Calusa?)

|

| Linguist List | 07y |

Archaeologists study the Glades culture, which included the Tequesta area. Their findings show that people in this region made pottery in a similar way from about 700 BCE. This continued even after Europeans arrived.

The Tequesta language might have been like the language of the Calusa people. The Calusa lived on Florida's southwest coast. It might also have been similar to the Mayaimi language. The Mayaimi lived around Lake Okeechobee. We only know about ten words from these languages.

People once thought the Tequesta were related to the Taino from the Caribbean islands. But most experts now think this is not true. This is because of what archaeologists have found. Also, the Tequesta had lived in Florida for a very long time.

What the Tequesta Ate

The Tequesta people did not farm. They got their food by fishing, hunting, and gathering plants. Most of their food came from the sea. A man named Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda lived with southern Florida tribes for 17 years in the 1500s. He said their usual diet was "fish, turtle and snails, and tunny and whale." Important people ate "sea-wolf" (Caribbean monk seal).

Fontaneda also said they ate trunkfish and lobster. The "fish" they caught included manatees, sharks, sailfish, porpoises, and stingrays. Even though there were many clams, oysters, and conches nearby, these were not a big part of the Tequesta diet. You find fewer shells from these at Tequesta sites than at Calusa or Jaega sites.

Venison (deer meat) was also popular. Deer bones are often found at their old living sites. They also ate terrapins and Sea turtles. They ate sea turtles and their eggs when the turtles laid them.

The Tequesta gathered many plant foods. These included berries from saw palmetto plants. They also ate cocoplums, sea grapes, and prickly pear fruits. Other foods were gopher apples, pigeon plums, and palm nuts. They also ate false mastic seeds, cabbage palm, and hog plum.

The roots of some plants, like Smilax and coontie, could be eaten. They would grind them into flour. Coontie roots needed special processing to remove toxins. Then, they made a type of flat bread from the flour.

The Tequesta moved their homes during the year. Many people from the main village went to barrier islands or the Florida Keys. They did this during the worst part of mosquito season, which lasted about three months. The food sources around Biscayne Bay and the Florida Keys allowed them to live without farming. However, these areas were not as rich in food as the southwest Florida coast, where the Calusa lived.

Homes and Clothes

A man named Briton Hammon said the Tequesta lived in "hutts." Other tribes in southern Florida lived in houses with wooden posts and raised floors. Their roofs were made of palmetto leaves, like the chickees of the Seminoles. These houses might have had temporary walls made of woven palmetto-leaf mats. These mats would block the wind or sun.

Their clothing was simple. Men wore a type of loincloth made from deer hide. Women wore skirts made of Spanish moss or plant fibers. These hung from a belt.

Customs and Beliefs

Tequesta men drank cassina, also known as the black drink. They used it in special ceremonies. These ceremonies were common in the southeastern United States.

Spanish missionaries said the Tequesta worshipped a stuffed deer. They believed it represented the sun. As late as 1743, they worshipped a picture of a barracuda that looked deformed. It had a harpoon through it and small tongue-like shapes around it. This picture was painted on a small board. They also had a "god of the graveyard," which was a bird's head carved from pine. The painted board and bird's head were kept in a "temple" in the cemetery. This temple also held carved masks used in festivals. By this time, the tribe's shaman (spiritual leader) was calling himself a "bishop."

The Tequesta also believed that humans had three souls. One soul was in the eyes, one in the shadow, and one in the reflection.

The Miami Circle

The Miami Circle is a special place. It is located where a Tequesta village once stood, south of the Miami River. This was likely the main town of "Tequesta." The Circle has 24 large holes or basins, and many smaller ones. These holes are cut into the bedrock. Together, they form a circle about 38 feet wide. Other patterns of holes can also be seen.

The Circle was found when workers were clearing land for a new building. Scientists tested charcoal found in the circle. They found it was about 1,900 years old (around 100 CE). Sea shells found at the site are even older, dating back to 730 BCE. This suggests that people lived here permanently for over 2,700 years. The Miami Circle is on the south side of the Miami River. Recent discoveries show a larger Tequesta site on the north side of the river. This site likely existed at the same time as the Miami Circle.

After Europeans Arrived

In 1513, Juan Ponce de León stopped at a bay in Florida. He called it Chequesta, which is now Biscayne Bay. In 1565, one of Pedro Menéndez de Avilés' ships found shelter from a storm in Biscayne Bay. The main Tequesta village was there. The Tequesta welcomed Menéndez.

Jesuit priests with Menéndez took the Tequesta chief's nephew to Havana, Cuba, for schooling. The chief's brother went to Spain with Menéndez and became a Christian. In 1567, Menéndez came back to the Tequesta. He built a mission inside a fort near the south bank of the Miami River. He left 30 soldiers and a Jesuit brother, Francisco Villareal, to teach the Tequesta about Christianity. Villareal had learned some Tequesta language from the chief's nephew. He felt he was making progress until the soldiers killed an uncle of the chief. Brother Francisco had to leave the mission for a while. When the chief's brother returned from Spain, Brother Francisco could come back. However, the mission closed soon after, in 1570.

Starting in 1704, the Spanish government wanted to move Florida Indians to Cuba. There, they could learn about the Catholic faith. The first group of Indians, including the chief of Key West, arrived in Cuba in 1704. Most of them soon died. In 1710, 280 Florida Indians were taken to Cuba. Almost 200 of them died quickly. The ones who survived went back to the Keys in 1716 or 1718. In 1732, some Indians from the Keys escaped to Cuba.

In 1743, the Governor of Cuba received a request from three Calusa chiefs. They were visiting Havana. The request was written in good Spanish. It showed they understood how the government and church worked. They asked for missionaries to be sent to the Florida Keys to teach them about religion. The Governor decided it would be cheaper to send missionaries to the Keys. This way, the Indians would be there to help Spanish sailors whose ships crashed. They would also help keep the English out of the area.

The governor sent two Jesuit missionaries from Havana, Fathers Mónaco and Alaña. They had soldiers with them. When they reached Biscayne Bay, they built a chapel and a fort. It was at the mouth of a river they called the Rio Ratones. This might have been the Little River or the Miami River.

The Spanish missionaries were not well received. The Indians in the Keys said they had not asked for missionaries. They allowed a mission to be built because the Spanish brought gifts. But the chief said the King of Spain did not rule his land. He demanded payment for letting the Spanish build a church or bring settlers. The Indians asked for food, rum, and clothes. But they refused to work for the Spanish. Father Morano reported attacks on the mission by groups of Uchizas. These were the Creeks who later became known as Seminoles.

Fathers Mónaco and Alaña planned to have 25 soldiers at the fort. They also wanted to bring Spanish settlers to grow food for the soldiers and Indians. They thought this new settlement would soon be as important as St. Augustine. Father Alaña went back to Havana. He left 12 soldiers and a corporal to protect Father Mónaco.

The governor in Havana was not happy. He ordered Father Mónaco and the soldiers to leave. He also ordered the fort to be burned so the Uchizas could not use it. He sent the missionaries' plan to Spain. There, the Council of the Indies decided the mission on Biscayne Bay would be too expensive and not practical. This second attempt to build a mission on Biscayne Bay lasted less than three months.

When Spain gave Florida to Britain in 1763, the remaining Tequesta people moved to Cuba. Other Indians who had found safety in the Florida Keys also moved. In the 1770s, Bernard Romans saw abandoned villages in the area. But no people were living there.

See also

- Pompano Beach Mound: another Tequesta archaeological site

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |