Geography and ecology of the Everglades facts for kids

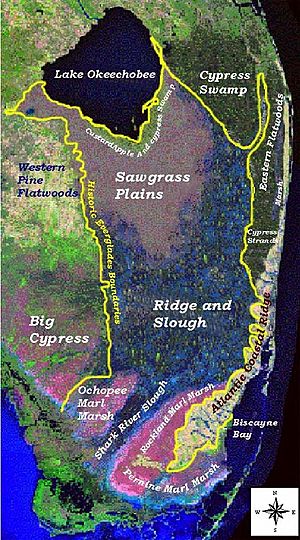

The Everglades are a huge area of wetlands in southern Florida. Before people started draining them, they covered about 4,000 square miles (10,000 km²). This unique place is like a giant, slow-moving river, often called the "River of Grass" because of its wide, shallow flow and tall sawgrass. It stretches about 100 miles (160 km) from Lake Okeechobee south to Florida Bay.

The Everglades is a special mix of water, land, and climate. It's home to many different natural areas. While sawgrass marshes are famous, other parts are just as important. These include pine forests, tropical hardwood hammocks, and huge cypress swamps. As the fresh water from Lake Okeechobee moves south, it meets the salty water from the Gulf of Mexico. Here, mangrove forests grow, providing safe homes for many birds, fish, and other creatures. Even Florida Bay is part of the Everglades because its sea life depends on the fresh water flowing in.

These natural systems are always changing. Things like the shape of the land, the weather, and how often storms and fires happen all help shape the Everglades. Even small changes in water levels can have big effects on the plants and animals that live here.

Contents

How the Everglades Were Shaped

The Everglades are quite young in terms of Earth's history, only about 5,000 years old. Their different natural areas are constantly changing because of three main things: the amount and type of water, the ground (geology), and how often fires happen.

Water's Role

Water is the most important part of the Everglades. It shapes the land, plants, and animals in South Florida. Thousands of years ago, the sea level rose, covering parts of Florida and making the underground water level higher. Fresh water soaked into the limestone rock, slowly dissolving it and creating springs and sinkholes. This abundance of fresh water allowed new plants to grow, and the evaporation created thunderstorms. Over time, the limestone wore away, and water came to the surface, forming this massive wetland. Even though it looks flat, tiny differences in elevation (just inches!) affect how water flows and what plants grow.

The Everglades are special because they get most of their water from rain. Before people started draining it in 1882, the entire water system stretched from Orlando all the way to Florida Bay. There are only two seasons in the Everglades: wet (May to November) and dry (December to April). About 62 inches (157 cm) of rain fall each year, but this can change a lot. Droughts, floods, and tropical storms are normal. When Lake Okeechobee gets too full, its water slowly spills over the southern edge and flows 100 miles (160 km) to Florida Bay. The land is so flat that the water moves very slowly, only about 2 feet (0.6 meters) per minute. This slow-moving water is perfect for sawgrass.

Big storms like hurricanes also change the Everglades. Between 1871 and 2003, 40 tropical cyclones hit the area. These storms change the coastline, clean out old plants from river mouths, break weak tree branches, and spread seeds. For example, Hurricane Donna in 1960 covered 120 square miles (310 km²) of mangrove forests with mud, stopping the trees from getting oxygen. It also destroyed many orchids and bromeliads that grew on the mangroves. While some plants take a long time to return, storms can also help by spreading new plants and improving nesting spots for crocodiles and sea turtles.

Geology's Influence

The vast marshland of the Everglades could only form because of the rocks underneath southern Florida. The ground of the Everglades was created between 25 million and 2 million years ago when Florida was a shallow sea floor. Layers of calcium carbonate (like tiny shells) were pressed together by ocean water, forming porous limestone. This rock can store water for a long time. The amount of time an area stays flooded, called a hydroperiod, decides what kind of soil and plants will be there.

If an area is flooded for only three or four months, a type of algae called periphyton grows. Periphyton is the main ingredient of marl, a chalky mud. In areas flooded for more than nine months, peat builds up over hundreds or thousands of years from decaying plants. Both peat and marl are poor in nutrients, but they allow special plants to grow depending on how long the water stays.

There are five types of peat in the Everglades, and each supports different plants like sawgrass or tree islands. Peat builds up because water stops oxygen from breaking down dead plants quickly. But when peat dries out, it decays fast, a process called subsidence. Early farms near Lake Okeechobee saw their peat soils disappear quickly. Some homes even had to add stilts because the ground sank! Between the 1880s and 2005, about 3.4 billion metric tons of soil were lost in the Everglades, mostly in farming areas.

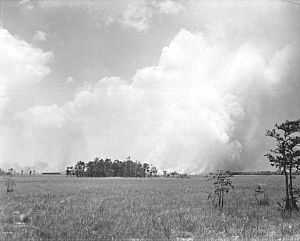

Fire's Importance

Fire is another key part of keeping the Everglades healthy. Most fires are caused by lightning during the wet season. These fires usually burn only the top parts of plants, helping new growth. Fire in sawgrass marshes keeps out larger bushes and trees, and it releases nutrients from dead plants more efficiently than natural decay. Large burned areas also help water flow faster. During the wet season, only dead plants burn, but in the dry season, fires can burn deep into the organic peat, destroying plant roots. The only thing that stops fire in the Everglades is water. It takes about 225 years for one foot (0.3 meters) of peat to grow, but scientists believe fires are why the peat isn't as dense as it should be for the Everglades' age.

Scientists have noticed that fires happen in cycles, linked to water levels. There are annual wet-season fires that are quickly put out. Dry-season fires are rarer but can cause more damage. A longer fire cycle of 10 to 14 years is linked to global climate. The longest cycle, about 550 years, is connected to severe droughts. Layers of charcoal in the peat show that the Everglades had very bad fires for years at a time in the past.

Everglades Ecosystems

The Everglades are mostly covered by sawgrass growing in water, which is why it's called the "River of Grass." This river is full of many different plants and animals. An early environmentalist, Gifford Pinchot, said the Everglades felt like a different country, full of amazing life.

The sawgrass grows in wide, shallow channels of water, forming a river about 100 miles (160 km) long and 60 miles (97 km) wide, flowing from Lake Okeechobee to Florida Bay. Before drainage began in 1905, this wide, shallow river covered almost a third of southern Florida. While sawgrass is the main feature, other ecosystems are mixed in, and their boundaries can be hard to see.

Sawgrass Marsh

Most marshes in the Everglades are dominated by sawgrass. This plant has a three-dimensional, V-shaped stalk with upward-pointing teeth. Sawgrass loves the slow-moving water, but it can die if its roots don't get enough oxygen, especially after a fire. Some sawgrass can grow up to 6 feet (1.8 meters) tall, and even 10 feet (3 meters) tall near Lake Okeechobee. Farther south, it usually grows about 4 feet (1.2 meters) tall in patches. These marshes are typically flooded for nine months or longer.

Where sawgrass grows very thickly, not many other animals or plants can thrive, though alligators often build their nests there. In more open areas, periphyton grows. This is mostly algae mixed with over 100 other tiny living things. Periphyton provides food for larval insects and amphibians, which then become food for birds, fish, and reptiles.

Freshwater Sloughs

Sloughs are deeper channels of free-flowing water found between the sawgrass marshes. They are about 3 feet (0.9 meters) deep and can stay flooded for at least 11 months, or even several years. The peat beds that support sawgrass are slightly higher, creating "ridge-and-slough" landscapes. Aquatic animals like turtles, young alligators, snakes, and fish live in sloughs. They often eat water insects like the Florida apple snail. Plants like waterlilies also grow here, usually submerged or floating. Important sloughs include the Shark River Slough, Lostmans Slough, and Taylor Slough.

Wet Prairie

Two types of wet prairies exist in the Everglades: marl prairies and water-marsh communities. Wet prairies are slightly higher than sawgrass marshes and have many different plants. Marl prairies are where marl covers limestone, which can stick out as peaks or erode into "solution holes." Solution holes are depressions filled with rainwater. The surface of marl prairies is only covered by water for three to seven months a year, and the water is usually only about 4 inches (10 cm) deep. Marl is a crumbly, grey or white mud when dry. When flooded, it supports various water plants, and small cypress trees can grow for hundreds of years but stay under 10 feet (3 meters) tall. Solution holes can stay flooded even when the prairies are dry, providing homes for aquatic animals like crayfish and snails, and young amphibians that feed wading birds.

Alligators create special spots in wet prairies. They dig low areas with their claws and snouts, making ponds that stay flooded during the dry season. These "alligator holes" are crucial for the survival of many aquatic animals, turtles, fish, small mammals, and birds during droughts. Alligators then feed on the animals that visit these holes.

Tropical Hardwood Hammock

Islands of dense trees, either temperate or tropical, are called tropical hardwood hammocks. They rise about 1 to 3 feet (0.3 to 0.9 meters) above the water in sloughs, sawgrass prairies, or pine forests. These islands show how the Everglades climate is a mix of tropical and subtropical. Hammocks in the northern Everglades have more temperate plants, while those closer to Florida Bay have tropical trees and smaller shrubs. Tropical trees like West Indian mahogany were likely spread by birds carrying seeds from the West Indies.

These hammocks form on slightly raised areas that are not harmed by deep peat fires or on limestone plateaus. They have a mix of subtropical and hardwood trees that grow very close together, like southern live oak, gumbo limbo, and royal palm. Sharp saw palmettos grow near the bases, making them hard to enter. Water in sloughs flows around these islands, creating moats that protect them from fire. Hammocks can take decades or centuries to recover from fire, so these moats are very important. The islands vary in size, usually between 1 and 10 acres (0.4 to 4 hectares). The slow-flowing water around them limits their size and makes them look like teardrops from above. Most trees in hammocks don't grow taller than 55 feet (17 meters) due to frost, lightning, and wind.

Florida strangler figs are common in hammocks. They often start growing on cabbage palms. As they grow, they wrap around the host tree, eventually blocking its light and nutrients, and taking its place. Many small animals like beetles, ants, spiders, and tree snails live here, supporting a food chain that includes frogs, owls, snakes, rodents, bobcats, and raccoons. There are over 50 types of tree snails in the Everglades, and their unique colors on different islands might be because the hammocks are isolated.

In the past, people cut down trees in tropical hardwood hammocks for wood, especially West Indian mahogany for shipbuilding. Most of the largest trees were removed by the late 1700s. The Seminole people built their villages in hammocks in the late 1800s and early 1900s. They lived in groups of half a dozen chickees (open-sided houses), with one central chickee for cooking. You can still find old dugout canoes and tools in remote areas.

Bayheads and Willowheads

Some hammocks are named after the main types of trees that grow there, depending on the water or soil. Most hardwood hammocks create a thin, rich soil called humus over the limestone. When peat forms the layer on a tree island, it becomes a bayhead, dominated by bay trees like sweetbay magnolia. Willowheads, full of willow trees, grow where the water stays for a long time, often around solution or alligator holes, sometimes surrounding them like a donut from above.

Flatwoods and the Atlantic Coastal Ridge

The wide prairies and sloughs of the Everglades are bordered by two areas of sandy soil that don't drain well, on both sides of Lake Okeechobee. These are the Eastern Flatwoods and the Western Flatwoods (north of Big Cypress Swamp). The main ecosystem in the Flatwoods is pine forest, but there are also cypress swamps and sloughs in the Eastern Flatwoods. Along the eastern edge of the Everglades is the Atlantic Coastal Ridge, which rises about 20 feet (6 meters) high. This ridge curves southwest, gradually getting lower, until it meets Taylor Slough. The Coastal Ridge stops Everglades water from flowing into the Atlantic Ocean to the east, directing it southwest into Florida Bay. The South Florida metropolitan area (where cities like Miami are) is built on part of this ridge, and much of the land has changed a lot in the last 100 years due to city growth.

Pine Rockland

Pine rocklands (also called pinelands) grow on uneven limestone ground with peaks and holes. There are three main places where you find pine rocklands: the Miami Ridge (from Miami to Long Pine Key in Everglades National Park), the lower Florida Keys, and the Big Cypress Swamp. The most important tree here is the South Florida slash pine, which can grow to 22 feet (6.7 meters) tall.

Pine rockland communities need fire to stay healthy. They have adapted to both encourage and resist fire. These areas are the highest parts of the Everglades and usually don't stay flooded for long, though some holes might have water for a few months. The sandy ground is covered with dry pine needles that burn easily. South Florida slash pines have thick bark that protects them from heat. Fire removes other plants that compete with the pines and helps pine cones open to release seeds. If there isn't enough fire, larger trees can take over, turning the pineland into a hardwood hammock. Today, controlled fires are set in Everglades National Park every three to seven years to keep these pine rocklands healthy.

Pine rocklands are home to many animals. You can find 15 species of birds in some forests, like the pine warbler and the red-bellied woodpecker. More than 20 types of reptiles and amphibians live here, such as the green anole and the southern black racer. Mammals like the critically endangered Florida panther, Florida black bear, and several types of bats also live in the pine rocklands.

Before cities grew in South Florida, pine rocklands covered about 161,660 acres (654 km²) in Miami-Dade County. Many pine forests were cut down for city development and lumber in the 1930s and 1940s. Inside Everglades National Park, 19,840 acres (80 km²) of pine rockland are protected. But outside the park, only about 1,780 acres (7 km²) remained in 1990, in small patches. Dade County pine wood is very strong and resists termites. In 1984, a local law protected these pines after many areas were lost. People also didn't understand how important fire was, so natural fires were put out, causing pine rocklands to change into hardwood hammocks.

The Big Cypress Swamp

West of the sawgrass prairies is the Big Cypress Swamp, often just called "The Big Cypress." It's named for its huge size, not necessarily for the height of its trees. It covers most of Collier County, and its water boundary is almost twice as large as its smallest measurement of 1,200 square miles (3,100 km²). The Big Cypress is slightly higher than the Everglades, at 22 feet (6.7 meters) at its highest point, and slopes gradually to the coast for about 35 miles (56 km). It's called a swamp because it has so many trees, unlike a marsh which is mostly grass.

The Big Cypress basin gets about 55 inches (140 cm) of water during the rainy season. Most of it sits on a bedrock covered by a thin layer of limestone mixed with quartz, creating sandy soil that supports many different plants. The main trees are bald cypress and pond cypresses. Cypresses are unique cone-bearing trees that can live in flooded conditions. They have wide, flared trunks and root projections called "knees" that stick out of the water.

Cypress trees here can live for hundreds of years; some are 130 feet (40 meters) tall and 500 years old. However, few massive trees survived the logging that happened in the 1930s and 1940s. Today, much of The Big Cypress is protected by different government agencies, including Big Cypress National Preserve, Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary, and Fakahatchee Strand State Preserve.

Cypress Head Ecosystem

While The Big Cypress is the largest cypress swamp in South Florida, smaller cypress swamps can be found near the Atlantic Coastal Ridge and between Lake Okeechobee and the Eastern flatwoods. Hardwood hammocks and pine forests are often mixed with the cypress ecosystem. Like tree islands, cypress trees often grow in dome-shaped formations, with the tallest and thickest trunks in the center where the peat is deepest. As the peat gets thinner, the cypresses become smaller, giving the forest a dome-like look. They also grow in strands, slightly raised on limestone plateaus and surrounded by sloughs. Other hardwood trees like red maple and swamp bay can be found in cypress domes. If cypresses are removed, hardwoods take over, and the area becomes a mixed swamp forest.

Because cypress domes and strands stay moist and block out a lot of sunlight, plants like orchids, bromeliads, and ferns thrive there. Orchids bloom all year, and many types of bromeliads grow. Bromeliads collect water in their leaves, providing homes for frogs, lizards, and insects. Wood storks nest almost only in cypress forests. Their numbers have dropped a lot in the last 100 years, likely because of how water is managed. Wood storks need dry seasons to find small fish and amphibians trapped in shallow pools for their young. If water is released too soon or not at all, storks can't find enough food. In the 1930s, about 20,000 wood storks nested in The Big Cypress, but by the 1990s, fewer than 2,000 were counted.

Mangroves and Coastal Prairie

Water from Lake Okeechobee and The Big Cypress eventually flows to the ocean. In a special area where fresh water meets salt water, mangrove trees grow. They are adapted to live in both kinds of water. This mix of salty and fresh water, with hundreds of tidal creeks, creates a very productive ecosystem. How deep these zones are depends on how much water flows from the Everglades. In the wet season, fresh water pours into Florida Bay, and sawgrass can even grow near the coast. In drier years, salt water moves further inland into the coastal prairie, which acts like a buffer for the freshwater marshes by soaking up sea water. Mangrove trees can even grow in freshwater areas if the salt water reaches far enough inland. The Everglades has the largest continuous system of mangroves in the world. The mangrove forests of the Ten Thousand Islands cover almost 200,000 acres (800 km²).

Mangrove Trees

There are three types of mangrove trees in the region: red, black, and white. Even though they are from different plant families, they all share common traits: they can handle salt, brackish (mixed salt and fresh), and fresh water; they grow in soil with little oxygen; and they can survive big changes in water levels. Black and white mangroves get rid of salt from under their leaves, while red mangroves filter the salt from sea water. All three types are vital for protecting the coastline during severe storms. Red mangroves, for example, have long roots that trap sediments. The trees not only make coastlines stable but also help create new land as more sand and decaying plants get caught in their root systems. All three mangroves also absorb the energy from waves and storm surges.

The areas where rivers meet the sea (estuaries) act as nurseries for young fish and crustaceans. Shrimp, oysters, crabs, and snails thrive in these waters. Between 80 and 90 percent of the seafood caught commercially in Florida are born or spend time in the shallow waters near the Everglades. Oysters and mangroves work together to build up the coastline. Oyster colonies grow and deposit their shells, strengthening the ground. Mangrove seeds, called propagules, are full embryos that float until they find a good spot to root, often on oyster beds.

Mangroves are also excellent places for birds to raise their young. Wading birds like roseate spoonbills, egrets, and tricolored herons use the mangroves as nurseries. This is because food sources are close by, and the dense trees offer protection from predators. Thousands of birds can nest in the mangroves at once. Their droppings also help fertilize the mangrove trees. Over 100 species of birds, including shorebirds, diving birds, and birds of prey like ospreys, use Everglades mangrove trees to raise their young.

Florida Bay

Because much of the coast and inner estuaries are built by mangroves, and there's no clear border between the coastal marshes and the bay, the ecosystems in Florida Bay are considered part of the Everglades. More than 800 square miles (2,070 km²) of Florida Bay are protected by Everglades National Park, making it the largest body of water in the park. There are about one hundred small islands (called keys) in Florida Bay, many of which are mangrove forests. Larger islands might have hardwood hammocks. The outer edges of the Ten Thousand Islands and Cape Sable share characteristics of these mixed saltwater bays and freshwater marshes.

The fresh water flowing into Florida Bay from the Everglades creates perfect conditions for large beds of turtle grass and algae. These support animal life in the bay. Sea turtles and manatees eat the grass, while invertebrates like worms and clams eat algae and tiny plankton. Female sea turtles return every year to nest on the shore, and manatees spend the winter in the bay's warmer waters. The Calusa Indians used shells from marine invertebrates for tools because there wasn't much hard rock.

Sea grasses make the sea floor stable and protect shorelines from erosion by absorbing wave energy. Shrimp, spiny lobsters, and sea urchins live among the grasses and eat tiny plants. They, in turn, become food for larger predators like sharks, rays, and barracuda. Because the water is shallow and gets a lot of sunlight, Florida Bay has coral reefs and sponges, though most of Florida's reefs are closer to the Florida Keys. Everglades keys with mangroves also support nurseries for wading birds like the Great blue heron. This bird was almost wiped out by the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935 (only 146 were left). After recovering to over 2,000, their numbers dropped again by 35 to 40 percent after Hurricane Donna in 1960.

The patterns on the sea floor of Florida Bay are shaped by currents and winds. However, since 1932, sea levels have been rising at a rate of 1 foot (0.3 meters) every 100 years. While mangroves help build and stabilize the coastline, the seas might be rising faster than the trees can build new land.

Amazing Biodiversity

The Everglades ecosystems are both delicate and strong. Author Michael Grunwald described the Everglades as a "complex drama, and everything in it had a role." About 11,000 species of seed-bearing plants and 400 species of land or water animals with backbones live in the Everglades. But even small changes in water levels can affect many organisms and reshape the land. The health of any ecosystem depends on how many different species are present: if one species is lost, the whole ecosystem becomes weaker.

For example, Florida apple snails are freshwater snails that can live both in water and on land. They have a gill and a lung, and they live on sawgrass stalks in water no deeper than 20 inches (51 cm). They are the main food for the endangered snail kite and limpkin, as well as raccoons, otters, and young alligators. Apple snails lay their eggs on sawgrass stalks about 6 inches (15 cm) above the water line. They cannot survive being underwater for long periods. When the eggs hatch, young snails must enter the water quickly or they will die. If water levels are too low or rise too quickly while snail eggs are developing, apple snails don't do well. This then affects the many reptiles, mammals, and birds that eat them. The 174 species of invertebrates (animals without backbones) play a vital role in the Everglades food chains. Crayfish, insects, and scorpions also support a network of animals.

Freshwater fish are crucial for the overall success of Everglades wildlife. Few places in the Everglades stay flooded all year, so alligator holes and deep cracks in the limestone are vital for fish to survive, and for the whole animal community. Freshwater fish are the main food for most wading birds, alligators, and otters. They need large areas of open water to reproduce. Young amphibians also play an important role in the food chain. Tadpoles spread quickly in isolated areas where fish don't have enough time or access to reproduce in large numbers to support bigger animals. Hundreds of species of amphibians are found in the Everglades, and their presence helps support wildlife during short dry periods or in remote locations.

These smaller animals support larger ones, including 70 species of land birds that breed in the Everglades, and 120 water birds, with 43 breeding in the area. Many of these birds migrate through the West Indies and North America. Several dozen species of mammals also thrive here, from tiny bats and shrews to mid-sized raccoons, otters, and foxes. The largest include white tailed deer, the Florida black bear, and the Florida panther.

Even though small changes in water level affect many species, the entire system also changes and adapts with each shift. Some changes to plant and animal diversity are natural, caused by fire or storms. Others are caused by humans, such as cities expanding, the introduction of new species, and rapid global warming. The Everglades' environment doesn't favor any single species. Some, like snail kites and apple snails, do well in wet conditions, while wood storks and Cape Sable seaside sparrows do better in drier times.

Human Impact on the Everglades

Development and Restoration

People have lived in the Everglades for thousands of years. However, in the last 100 years, they have changed the natural landscape dramatically. Cities in South Florida grew very fast, helped by large drainage projects meant to create more land. These drainage efforts were often done without fully understanding how the Everglades' complex ecosystems worked. The growth of cities caused problems throughout the Everglades. By the 1990s, the declining quality of life in these cities was linked to the damaged local environment. In 2000, the State of Florida and the U.S. government created and passed a plan to restore as much of the Everglades as possible to its original state. This is the most expensive and complete environmental restoration project in history.

Invasive Species

Humans have also harmed the Everglades' environment by bringing in many invasive species. These new species can hunt or compete with native animals. A very damaging example is the recent spread of the Burmese python in the Everglades and other parts of Florida. First seen in the wild in 1979, their numbers have grown alarmingly since 2000. By 2011, park surveys reported huge drops in sightings of bobcats (87.5%), white-tailed deer (94.1%), opossums (98.9%), and raccoons (99.3%). Rabbits were no longer seen at all.

Climate Change and Sea Level Rise

Mangroves in the Everglades are threatened by climate change, which is causing sea level rise.

See also

In Spanish: Geografía y ecología de los Everglades para niños

In Spanish: Geografía y ecología de los Everglades para niños

- Indigenous people of the Everglades region

- Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan

Images for kids

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |