Indigenous people of the Everglades region facts for kids

The indigenous people of the Everglades region were the first people to live in the Florida peninsula, arriving about 14,000 to 15,000 years ago. They likely followed large animals for hunting. Back then, Florida was a dry place with plants and animals that could live in prairies and dry scrublands.

About 11,000 years ago, many large animals in Florida died out. Then, around 6,500 years ago, the climate changed and became much wetter. The early people, called Paleo-Indians, slowly learned to live with these new conditions. Archaeologists call the groups that came from these changes the Archaic peoples. They were good at adapting to environmental changes and made many useful tools from the things they found. Around 5,000 years ago, the climate changed again, causing regular floods from Lake Okeechobee. This led to the creation of the unique Everglades ecosystem.

From the Archaic peoples, two main tribes grew in the area: the Calusa and the Tequesta. We know about them mostly from the writings of Spanish explorers, who wanted to convert them to Christianity and take over their lands. Even though these tribes had complex societies, not much physical evidence of their lives remains today.

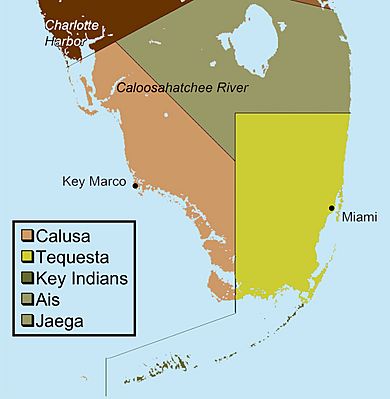

The Calusa were larger and more powerful. Their main area was around modern-day Ft. Myers. Their territory stretched north to Tampa, east to Lake Okeechobee, and south to the Keys. The Tequesta lived on the southeastern coast of Florida, near what is now Biscayne Bay and the Miami River. Both tribes were very good at living in the different parts of the Everglades. Their people often traveled through the heart of the Everglades, but they usually didn't live deep inside it.

After more than 210 years of contact with the Spanish, both Native American societies started to lose their strength. Records show that many survivors of wars and diseases were taken to Havana with Spanish settlers in the late 1700s, after Great Britain took control of some Florida lands. Some small groups might have joined the Seminole nation. This new tribe formed in northern Florida when a group of Creek people combined with the remaining members of older Florida tribes. Free Black people and escaped slaves, known as Black Seminoles, also joined them.

The U.S. military forced the Seminole south into the Everglades during the Seminole Wars (1835–1842). The military's pursuit of the Seminole led to some of the first recorded explorations of much of the Everglades by European-Americans. Today, federally recognized Seminole tribes still live in the Everglades region. Since the late 1900s, they have built casinos on their reservations in Florida, which help fund their tribes' welfare and education.

Contents

Early Peoples of Florida

| Period | Dates |

|---|---|

| Paleo-Indian | 10,000–7,000 BCE |

| Archaic: Early Middle Late |

7,000–5,000 BCE 5,000–3,000 BCE 3,000–1,500 BCE |

| Transitional | 1,500–500 BCE |

| Glades I | 500 BCE–800 CE |

| Glades II | 800–1200 |

| Glades III | 1200–1566 |

| Historic | 1566–1763 |

Humans first lived in Florida about 14,000 to 15,000 years ago. At that time, Florida looked very different and had a different climate. The west coast stretched about 100 miles (160 km) farther west than it does today. The land was dry with large sand dunes and strong winds. Plants were mostly small oak trees and scrub bushes. As Earth's ice sheets melted, the winds slowed down, and more varied plants grew.

The Paleo-Indians ate small plants and hunted wild animals. These animals included saber-toothed cats, ground sloths, and spectacled bears. Most of these large animals died out around 11,000 years ago. Around 6,500 years ago, Florida's climate became much wetter. Paleo-Indians started spending more time in camps and less time traveling to find water.

The Paleo-Indians who survived are known as the Archaic peoples of Florida. After most large animals became extinct, they became mostly hunter-gatherers. They hunted smaller animals and fish, and relied more on plants for food than their ancestors. They were able to adapt to the changing climate and the new animal and plant populations.

Florida went through a long drought at the start of the Early Archaic period. It lasted until the Middle Archaic period. Even though the population decreased, these people started using many more tools. They made drills, knives, choppers, atlatls (spear throwers), and awls (small pointed tools). These tools were made from stone, antlers, and bone.

During the Late Archaic period, the climate became wetter again. By about 3000 BCE, rising water tables allowed the population to grow. New cultural developments also happened. Florida Indians formed three similar but distinct cultures: the Okeechobee, Caloosahatchee, and Glades cultures. They were named after the bodies of water where they lived.

The Glades culture is divided into three periods based on findings in middens (ancient trash heaps). In 1947, archaeologist John Goggin studied shell mounds to describe these periods. The Glades I culture (500 BCE to 800 CE) was simpler, with mostly plain pottery. The Glades II period (starting 800 CE) showed a more developed culture. Pottery became more decorative, and tools were used widely. Religious items also appeared at burial sites. By 1200 CE, the Glades III culture reached its peak. Pottery had many types of decoration. They also made ceremonial ornaments from shells and built large earthworks for burial rituals. From the Glades III culture came the two main tribes of the Everglades in later times: the Calusa and the Tequesta.

The Calusa Tribe

What we know about Florida's people after 1566 comes from European explorers and settlers. Juan Ponce de León was the first European to meet Florida's native people in 1513. He faced resistance from tribes like the Ais and the Tequesta. Then he sailed around Cape Sable and met the Calusa, the largest and most powerful tribe in South Florida. Ponce de León found that at least one Calusa person spoke Spanish. He thought this person was from Hispaniola. However, anthropologists suggest that the Calusa often traded and communicated with people in Cuba and the Florida Keys. It's also possible Ponce de León wasn't the first Spaniard to meet them. During his second visit to South Florida, the Calusa killed Ponce de León. This gave the tribe a reputation for being fierce, and future explorers often avoided them. For over 200 years, the Calusa resisted Spanish attempts to convert them to Christianity.

The Spanish called the Calusa "Carlos," which might have sounded like "Calos." This word could be a form of the Muskogean word kalo, meaning "black" or "powerful." Much of what we know about the Calusa comes from Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda. He was a 13-year-old boy who was the only survivor of a shipwreck in 1545. He lived with the Calusa for seventeen years until explorer Pedro Menéndez de Avilés found him in 1566. Menéndez took Fontaneda to Spain, where he wrote about his experiences.

Menéndez wanted to build good relationships with the Calusa to help future Spanish settlement. The Calusa chief, or cacique, was called Carlos by the Spanish. Important leaders in Calusa society sometimes took names like Carlos and Felipe, similar to Spanish royal names. The cacique Carlos, described by Fontaneda, was the most powerful chief during the Spanish colonization. Menéndez tried to marry Carlos's sister to improve relations between the Spanish and the Calusa. This kind of family arrangement was common among South Florida tribes to settle disputes or make agreements. Menéndez was already married and felt uncomfortable with the union. He took Carlos's sister to Havana, where she was educated. One story says she died years later, and the marriage was never completed.

Fontaneda wrote in his 1571 memoir that Carlos controlled fifty villages. These villages were on Florida's west coast, around Lake Okeechobee (which they called Mayaimi), and on the Florida Keys (which they called Martires). Smaller tribes like the Ais and Jaega, who lived east of Lake Okeechobee, regularly paid tributes to Carlos. The Spanish thought the Calusa collected treasures from shipwrecks and shared the gold and silver with the Ais and Jaega, with Carlos getting most of it. The main Calusa village, where Carlos lived, was on Estero Bay at present-day Mound Key. This is where the Caloosahatchee River meets the Gulf of Mexico.

Fontaneda described some of their spiritual practices. The building of shell mounds of different sizes and shapes was also very important to the Calusa's spiritual beliefs. In 1895, Frank Hamilton Cushing excavated a huge shell mound on Key Marco. It had several built terraces hundreds of yards long. Cushing found over a thousand Calusa artifacts. These included tools made of bone and shell, pottery, human bones, masks, and animal carvings made of wood.

The Calusa, like the people before them, were hunter-gatherers. They ate small game, fish, turtles, alligators, shellfish, and various plants. Since the local limestone was soft and not good for tools, they made most of their tools from bone or teeth. They also used sharpened reeds. Their weapons included bows and arrows, atlatls, and spears. Most villages were located at river mouths or on key islands. They used canoes for travel. Shell mounds found in and around the Everglades often border old canoe trails. South Florida tribes often canoed through the Everglades, but they rarely lived deep inside them. Canoe trips to Cuba were also common.

Calusa villages often had more than 200 people, and their society was organized in a hierarchy (a system with different levels of power). Besides the cacique, there were also priests and warriors. Family ties helped maintain this hierarchy, and marriage between siblings was common among the elite. Fontaneda wrote that the Calusa had no gold or silver and wore little clothing. Men wore breechcloths woven from palms, and women wore similar coverings made from a grass that looked like wool. Only one type of building was described: Carlos met Menéndez in a large house with windows that could hold over a thousand people.

The Spanish found Carlos difficult to control, and their priests and the Calusa often fought. Carlos was killed by a Spanish soldier with a crossbow. After Carlos's death, the war chief Felipe took over, but the Spanish also killed him shortly after. At the start of the Spanish presence, the Calusa population was estimated to be between 4,000 and 7,000. Their power and population declined after Carlos's death. By 1697, their number was estimated at about 1,000. In the early 1700s, the Calusa were attacked by the Yamasee from the north. Many asked to be moved to Cuba, where almost 200 died of illness. Some later returned to Florida, and the remaining Calusa may have eventually joined the Seminole culture, which developed in the 1700s.

The Tequesta Tribe

Second in power and number to the Calusa in South Florida were the Tequesta (also known as Tekesta, Tequeste, and Tegesta). They lived in the southeastern part of the lower peninsula, in what is now Dade, Broward, and the southern half of Palm Beach counties. They might have been controlled by the Calusa, but sometimes they refused to obey the Calusa caciques, which led to wars. Like the Calusa, they rarely lived deep in the Everglades. Instead, they preferred the coastal prairies and pine rocklands east of the freshwater swamps. To their north, their territory bordered the Ais and Jaega tribes.

Like the Calusa, Tequesta societies were centered at the mouths of rivers. Their main village was probably on the Miami River or Little River. A large shell mound on the Little River shows where a village once stood. Although little remains of the Tequesta society, an important archaeological site called the Miami Circle was found in 1998 in downtown Miami. It might be the remains of a Tequesta structure. Its meaning is still being studied by archaeologists and anthropologists.

The Spanish described the Tequesta as greatly feared by sailors. They suspected the natives of harming and killing survivors of shipwrecks. Spanish priests wrote that the Tequesta performed special ceremonies to mark peace with other tribes. Like the Calusa, the Tequesta hunted small game. However, they relied more on roots and less on shellfish in their diets. They did not practice farming. They were skilled canoeists and hunted in the open ocean for what Fontaneda called whales, but were probably manatees. They would lasso the manatees and drive a stake through their snouts.

The first contact with Spanish explorers happened in 1513 when Juan Ponce de León stopped at a bay he called Chequescha, or Biscayne Bay. Finding the Tequesta unfriendly, he left to contact the Calusa. Menéndez met the Tequesta in 1565 and kept a friendly relationship with them. He built some houses and set up a mission. He also took the chief's nephew to Havana for education and the chief's brother to Spain.

After Menéndez visited, there are few records of the Tequesta. There's a mention of them in 1673, and later Spanish contact to convert them. The last record of the Tequesta as a distinct group was written in 1743 by a Spanish priest named Father Alaña. He described them being attacked by another tribe. Only 30 survivors remained, and the Spanish transported them to Havana. In 1770, a British surveyor described many deserted villages in the region where the Tequesta had lived. Archaeologist John Goggin suggested that by the time European Americans settled the area in 1820, any remaining Tequesta had joined the Seminole people. By 1820, most descriptions of Native Americans in Florida only mentioned the "Seminoles."

The Seminole and Miccosukee Tribes

After the Calusa and Tequesta tribes declined, Native Americans in southern Florida were called "Spanish Indians" in the 1740s. This was probably because they had friendlier relations with Spain. Between the Spanish defeat in the Seven Years' War in 1763 and the end of the American War of Independence in 1783, the United Kingdom ruled Florida. The first known use of the term "Seminolie" comes from a British Indian agent in 1771.

The beginnings of the tribe are not entirely clear. Records show that Creeks from modern-day Alabama and Georgia moved into Florida. They took in what was left of the older Florida tribes, forming the Creek Confederacy. This mixing of cultures is seen in the languages spoken by the Seminoles. These include various Muskogean languages, especially Hitchiti and Creek, as well as Timucuan. In the early 1800s, a U.S. Indian agent explained the Seminoles this way: "The word Seminole means runaway or broken off. Hence ... applicable to all the Indians in the Territory of Florida as all of them ran away ... from the Creek ... Nation." The word "Seminole" comes from a Spanish word "cimarron," which means "wild" or "runaway," like wild horses.

Creeks were known to include conquered tribes into their own. Some Africans escaping slavery from South Carolina and Georgia fled to Florida. They were drawn by Spanish promises of freedom if they converted to Catholicism, and they found their way into the tribe. Seminoles first settled in northern Florida. However, the 1823 Treaty of Moultrie Creek forced them to live on a 5 million acre (20,000 km²) Indian reservation north of Lake Okeechobee. They soon moved farther south. About 300 Seminoles, including groups of Miccosukees (a similar tribe who spoke a different language), lived in the Big Cypress area of the Everglades. Unlike the Calusa and Tequesta, the Seminole relied more on farming and raised domesticated animals. They also hunted and traded with European-American settlers. They lived in structures called chickees, which are open-sided huts with palm-thatched roofs. They probably learned this style from the Calusa.

In 1817, Andrew Jackson invaded Florida to speed up its annexation to the United States. This led to the First Seminole War. After Florida became a U.S. territory and more settlers arrived, conflicts between colonists and Seminoles became more frequent. The Second Seminole War (1835–1842) resulted in almost 4,000 Seminoles in Florida being displaced or killed. The Seminole Wars pushed the Native Americans farther south and into the Everglades. Those who did not find refuge in the Everglades were moved to Oklahoma Indian territory as part of Indian removal.

The Third Seminole War lasted from 1855 to 1859. During this war, 20 Seminoles were killed, and 240 were removed. By 1913, there were no more than 325 Seminoles left in the Everglades. They made their villages in hardwood hammocks. These are islands of hardwood trees that grew in rivers or pine rockland forests. Seminole diets included hominy (a corn dish), coontie roots, fish, turtles, venison, and small game. Villages were not large because hammocks were small, usually between one and 10 acres (4,000 m² to 40,000 m²).

When the Seminoles lived in northern Florida, they wore animal-skin clothing similar to the Creeks. The heat and humidity of the Everglades led them to change their style of dress. Seminoles replaced their heavier buckskins with clothing made of lighter cotton or silk for special occasions. These clothes often had unique calico patchwork designs.

The Seminole Wars increased the U.S. military's presence in the Everglades. This led to the exploration and mapping of many areas that had not been recorded before. In 1848, military officers who had mapped the Everglades were asked by Thomas Buckingham Smith if it was possible to drain the region for farming.

Modern Times

Between the end of the Third Seminole War and 1930, a few hundred Seminoles continued to live mostly isolated in the Everglades. Flood control and drainage projects started in the early 1900s. These projects opened up much land for development and greatly changed the natural environment. Some areas became flooded, while former swamps became dry and suitable for farming. These projects, along with the completion of the Tamiami Trail (a road that cut through the Everglades) in 1930, ended old ways of life but also brought new opportunities.

A steady stream of white developers and tourists came to the area. The native people began to work on local farms, ranches, and souvenir stands. They helped clear land for the town of Everglades. They were also "the best fire fighters [the National Park Service] could recruit" when Everglades National Park caught fire during droughts.

As cities in South Florida grew, the Miccosukee branch of the Seminoles became closely linked with the Everglades. They sought privacy but also served as a tourist attraction. They wrestled alligators, sold crafts, and gave eco-tours of their land. As of 2008, there are six Seminole and Miccosukee reservations across Florida. They feature casino gaming, which helps support the tribes.

See also

In Spanish: Pueblos indígenas de los Everglades para niños

In Spanish: Pueblos indígenas de los Everglades para niños

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |