1899 Coeur d'Alene labor confrontation facts for kids

The Coeur d'Alene, Idaho, labor riot of 1899 was a major conflict between miners and mine owners. It happened in the Coeur d'Alene mining district in northern Idaho. This event was the second big fight in the area during the 1890s. Union miners, led by the Western Federation of Miners, wanted all mines to hire union workers. They also wanted them to pay higher union wages. Like a similar event seven years earlier, the 1899 conflict turned violent. A non-union mining building was destroyed by dynamite. Several homes were burned, and two people died. After the riot, the military took control of the area.

The riot happened because miners were upset with mine owners. Some owners paid lower wages. They also hired secret agents to join the union and report back. Non-union miners sometimes refused to join the union or go on strike.

Contents

Understanding the Conflict

Miners' Strike of 1892

Miners in the Coeur d'Alene area went on strike in 1892. They were angry about wage cuts. The strike became violent when union miners found out about a Pinkerton agent. This agent had been secretly giving union information to the mine owners. After some people died, the U.S. Army came in. They occupied the area and forced the strike to end. This difficult event led to the creation of the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) the next year.

Second Military Stay in 1894

Many people in the area still supported unions. By 1894, most mines had union workers. These workers were part of the Knights of Labor.

More violence broke out in Coeur d'Alene during a national railroad strike in 1894. This was called the Pullman Strike. Union members attacked mines and workers who were not part of the union. Forty masked men shot and killed John Kneebone. He had spoken against union miners in 1892. Other union members kidnapped a mine manager. They also tried to blow up a building at the Bunker Hill mine.

Mine owners asked the Idaho governor for help. The governor then asked for federal troops. The idea was to stop problems with the Northern Pacific Railroad. President Grover Cleveland sent about 700 troops in July 1894. The Army's job was only to keep the railroads running. They were not supposed to get involved in local labor fights. The Army patrolled the train lines and reported no issues. The union members stopped their attacks to avoid another military occupation.

The Army kept reporting that the railroads were fine. They asked to leave the area. But the mine owners wanted the troops to stay. Eventually, the mine owners realized the Army would only protect the railroad. So, they agreed to let the troops leave. The Army left Coeur d'Alene in September 1894.

In December 1894, the Bunker Hill and Sullivan mine closed down. They did not want to agree to the union's demand for a $3.50 daily wage. The mine reopened in June 1895. It hired non-union workers who were paid less. Miners got $3.00 per day, and other workers got $2.50. The company said they would raise wages when lead and silver prices went up.

Leading Up to the 1899 Clash

The Bunker Hill Mining Company in Wardner was making good money. It had paid out over $600,000 in profits. But miners at Bunker Hill and Sullivan mines earned less than other miners. This difference was a lot of money for them back then. These mines were the only ones in the area that were not fully unionized.

In April 1899, the union tried to get more workers to join. The mine superintendent, Albert Burch, said the company would rather close for 20 years than recognize the union. He then fired 17 workers he thought were union members. He also told other union men to quit and collect their pay.

The Dynamite Express

The union strike at Wardner was not going well. Other WFM unions nearby worried that their mine owners would cut wages too. These other unions decided to support the Wardner strike. Union leaders met and planned a big show of strength for April 29.

On April 29, 250 union members took over a train in Burke. The train engineer later said he was forced at gunpoint. At each stop, more miners got on the train. In Mace, 100 men joined. At Frisco, the train stopped to load 80 wooden boxes. Each box held 50 pounds of dynamite. At Gem, 150 to 200 more miners got onto three extra freight cars. In Wallace, 200 miners were waiting. They had walked 7 miles from Mullan. About 1,000 men rode the train to Wardner. This was where the Bunker Hill mine's $250,000 mill was located.

Witnesses later said that most men on the train did not know about any planned violence. They thought it was just a big protest to scare the mine owners. However, the union had given masks and guns to 100 to 200 men. These men acted like a trained army. A pro-union newspaper wrote:

- "At no time did the demonstration assume the appearance of a disorganized mob. All the details were managed with the discipline and precision of a perfectly trained military organization."

County Sheriff James D. Young, who had union support, rode the train with the miners. In Wardner, Young stood on a rail car and told the group to leave. But they ignored him. Prosecutors later claimed Young had been paid by the WFM.

Word reached Wardner by phone that the union miners were coming. Most mine and mill workers had already run away. The crowd ordered the remaining workers out of the Bunker Hill mine and mill. Once outside, they were told to run. Some shots were fired at them as they ran. James Cheyne was shot in the hip. Then union miners shot him more as he lay on the ground. He died soon after. One union man, John Smith, was accidentally shot and killed by other union men.

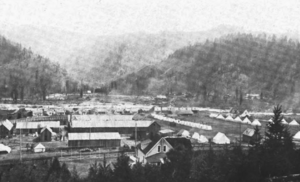

The miners carried 3,000 pounds of dynamite into the mill. The explosion completely destroyed the mill. The crowd also burned down the company office, a boarding house, and the mine manager's home. The miners then got back on the "Dynamite Express." They returned the way they came. Workers gathered along the tracks and cheered the union men as they passed.

Arrests and the Bullpen

The Idaho governor asked for help, and President William McKinley sent in the Army. Most of the soldiers sent to Coeur d'Alene were African American. They belonged to the 24th Infantry Regiment. This regiment had fought well in the Spanish–American War. It was known as a very disciplined Army unit. Bill Haywood criticized the government for trying to turn white people against black people.

State officials used the troops to arrest about 1,000 men. They put them into a temporary prison called "the bullpen." The arrests were not very careful. The governor's representative believed that all men in Canyon Creek should be arrested. Soldiers searched every house. They would break down doors if no one answered.

Mass arrests began on May 4, with 128 men arrested. More than 200 were arrested the next day. Arrests continued until about 1,000 men had been taken in.

Most of those arrested were freed within two weeks. By May 12, 450 prisoners remained. By May 30, the number was 194. Releases slowed down. Sixty-five men were still in jail on October 10. The last prisoners in the bullpen were released in early December 1899.

Aftermath of the Riot

Emma F. Langdon, who supported the union, wrote a book in 1908. She claimed that Idaho Governor Frank Steunenberg had been a "poor man." But he put $35,000 into his bank account a week after troops arrived. This suggested he might have been paid by the mine owners.

Governor Steunenberg was later killed by Harry Orchard. Orchard claimed the WFM had hired him.

Bill Haywood, a WFM leader, wrote about the miners' time in the "bull-pen." He said it was "unfit to house cattle." He believed that companies and their government supporters wanted to cut wages. They also wanted to fire union miners. Haywood thought this was a class war against working people.

Paul Corcoran, 34, was a union leader. He was charged by the state. He was not at the riot site. But he had been seen on the "Dynamite Express" train. He also rallied men at union halls along the way. He was sentenced to 17 years of hard labor. Eight more miners and union leaders were supposed to be tried for murder or arson. But they escaped after bribing an army sergeant. Hundreds more stayed in the makeshift prison without charges.

Meanwhile, a new system was created. It stopped mines from hiring any miner who belonged to a union. This plan aimed to destroy the unions in Coeur d'Alene. General Henry C. Merriam of the U.S. Army supported this system. This caused problems for President McKinley's White House.

Many elected officials in Shoshone County who supported the miners were arrested. The town sheriff of Mullan, Idaho was arrested and sent to the bullpen.

May Arkwright Hutton, whose husband was the engineer on the "Dynamite Express," wrote a book. It was called The coeur d' alenes: or, A Tale of the Modern Inquisition in Idaho. It was about how the miners were treated.

Both the Huttons and Ed Boyce, head of the Western Federation of Miners, had invested in the Hercules silver mine. This was before the 1899 conflict. After they became wealthy mine owners, May Hutton tried to buy back all copies of her book. Ed Boyce left the miners union to manage a hotel.