1st Weather Reconnaissance Squadron facts for kids

Quick facts for kids 1st Weather Reconnaissance Squadron |

|

|---|---|

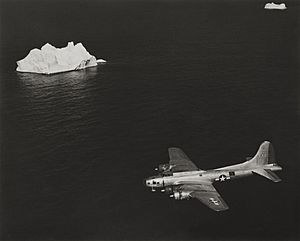

RB-17E #41-9140. Modified B-17s like this were used over the North Atlantic by the 1st & 53d Weather Reconnaissance Squadrons.

|

|

| Active | 1942–1945 |

| Country | United States |

| Branch | Army Air Forces |

| Type | Flying Squadron |

| Role | Weather Reconnaissance |

| Commanders | |

| Capt Arthur A. McCartan | 23 September 1942 |

| Lt Col Clark L. Hosmer | 23 June 1943 |

| Maj Karl T. Rauk | 14 August 1944 |

| Capt Sidney C. Bruce | 14 February 1945 |

| Insignia | |

| The Thunderbird – Emblem of the Army Air Forces Weather Reconnaissance Squadron (Test) Number One and subsequent units. Approved 26 March 1943. |  |

| Aircraft flown | |

| Bomber | A-28 Hudson |

| Reconnaissance | RB-17E Flying Fortress RB-17F Flying Fortress RB-17G Flying Fortress TB-25D Mitchell TB-25J Mitchell |

The 1st Weather Reconnaissance Squadron was a special flying unit of the United States Army Air Forces. It was active from April 1943 to December 1945. Its main job was to fly into bad weather to gather important information. This information helped other airplanes fly safely across the North Atlantic Ocean during World War II. The squadron was officially closed down at Grenier Field, New Hampshire, in December 1945.

Contents

Why Weather Reconnaissance Was Needed

Flying Planes Across the Atlantic

During World War II, the United States needed to send thousands of airplanes to Europe. These planes were used in battles across the European and Mediterranean areas. At first, smaller planes were taken apart and shipped by boat. But this was slow, and German submarines often attacked the ships.

So, a new way was found: the North Atlantic ferry route. This route involved a series of shorter flights. Planes would fly from Canada to Newfoundland, then to Labrador, Greenland, Iceland, and finally to the United Kingdom. By the summer of 1942, airfields were ready for large groups of planes to use this route.

The Challenge of North Atlantic Weather

Flying across the North Atlantic was very dangerous, especially in winter. The weather there is often stormy and unpredictable. Just like ships needed good weather forecasts, so did airplanes. Accurate weather forecasting was key to making these flights safer.

Before the war, the Army Air Forces (AAF) weather services were not big enough. They quickly built more weather stations and trained more weather experts. These stations were set up from eastern Canada all the way to Iceland. United States Coast Guard ships also helped by reporting weather from the ocean.

However, there were still huge gaps in the weather coverage. Storms could form in areas where no one was collecting data. The solution was to have special planes fly into these areas. These planes carried meteorologists, who are scientists who study weather.

What the Squadron Did

Gathering Weather Data

The main job of the 1st Weather Reconnaissance Squadron was to collect weather data. They flew over the North Atlantic ferry routes, especially the parts over the ocean. This data was then used to create forecasts. These forecasts helped ensure that aircraft flying between North America and Britain could travel safely.

There were three main routes planes used. Two routes involved short flights from Canada, through Greenland and Iceland, to Scotland. Airplanes could also fly directly from Canada to Scotland. The squadron provided weather information for all these paths.

How the Squadron Was Organized

Starting the Squadron

Discussions about forming weather reconnaissance squadrons began in 1941. In August 1942, the Army Air Forces Weather Reconnaissance Squadron (Test) Number One was officially created. It was based at Patterson Field in Ohio. Its first task was to figure out what equipment, people, and methods were best for collecting weather data during flights. This research was supposed to help create other operational squadrons.

The squadron became fully active in April 1943. It moved to Truax Field in Wisconsin for training. In June, its main office moved to Presque Isle Army Air Field, Maine. Here, Lt. Col. Clark L. Hosmer took command.

A Key Leader: Clark Hosmer

Clark Hosmer was a very important person in the AAF's weather services. He was a pilot and a weather expert. In 1941, he led a small weather team in Newfoundland. He helped set up weather stations across the North Atlantic. His work helped reduce accidents for planes flying to Britain. When the 1st Weather Reconnaissance Squadron became active, he was the perfect choice to lead it. He commanded the squadron for 14 months. During this time, he and 58 of his crew members received medals for their excellent work.

Changes and Final Days

In December 1943, the squadron's name changed to the 30th Weather Reconnaissance Squadron. It was then assigned to Air Transport Command (ATC). ATC was responsible for moving cargo, passengers, and planes all over the world during the war.

In August 1944, the squadron changed its name again to the 1st Weather Reconnaissance Squadron. Its headquarters moved to Grenier Field in New Hampshire. By early 1945, the war in Europe was nearing its end. Fewer planes were being sent across the Atlantic. The squadron was reorganized in February 1945. Its mission and some of its planes were given to another unit. The 1st Squadron continued with fewer operations. In December 1945, the squadron was officially closed down.

Squadron Equipment

Aircraft Used for Weather Missions

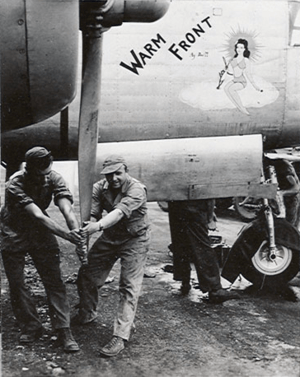

When the squadron started its operations in 1943, it first used a single Lockheed Hudson plane. This plane was not ideal, and production was stopping. So, the squadron switched to a modified version of the North American B-25 Mitchell. These planes were called TB-25Ds and TB-25Js.

The weapons, turrets, and armor were removed from these B-25s. This made the planes lighter. Extra fuel tanks were added in the bomb bay. This allowed them to fly longer distances. A typical crew included a pilot, co-pilot, navigator, weather officer, radio operator, and flight engineer.

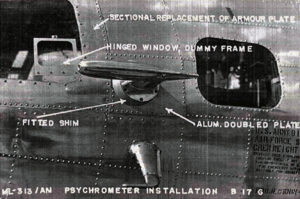

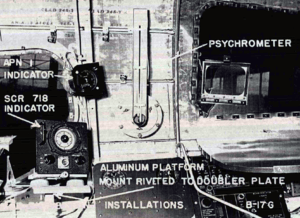

For winter missions, the squadron also used B-17 Flying Fortress planes. These were heavier, four-engine aircraft that could handle rougher weather. They were called RB-17Es, RB-17Fs, and RB-17Gs. Like the B-25s, their weapons were removed, and extra fuel tanks were added.

Special Weather Instruments

The planes were fitted with special instruments to collect weather data:

- Psychrometers: These had two thermometers, one wet and one dry. By comparing their temperatures, they could measure how much moisture was in the air (humidity). Special designs were needed because the fast-moving air outside the plane would heat the thermometers, making readings inaccurate.

- Aerograph: This instrument combined three sensors: for air pressure, humidity, and temperature. It drew graphs on a paper chart, creating a continuous record of conditions during the flight.

- Radio Altimeter: This measured the plane's true height above the sea. Over land, it measured height above the ground directly below.

- Pressure Altimeter: This measured altitude based on air pressure. By using both altimeters, weather officers could figure out the true air pressure at different heights.

- Other Tools: These included thermometers for outside air temperature, cameras for cloud photos, and equipment to prevent ice from forming on the plane.

How Observations Were Made

The Weather Officer's Job

The main goal of every mission was to get a trained weather officer and their instruments into the air. The success of the mission depended on how accurately they recorded their observations.

The weather officer sat in the nose of the airplane, where a bombardier would normally be. This spot offered great views of the sky and the ocean below. The officer watched the visible conditions outside and read the instruments.

They recorded:

- Humidity: From the psychrometer and aerograph.

- Temperature: From the free air thermometer and aerograph.

- Altitude and Air Pressure: Using both altimeters and the aerograph. They would record air pressure at specific heights, like 5,000 and 10,000 feet.

- Wind: They figured out wind speed and direction by watching how the plane drifted off course.

- Fronts: They looked for sudden changes in temperature and humidity on the aerograph chart. This helped them find cold fronts.

- Clouds and Icing: They observed the height, type, and amount of clouds. They also noted any ice forming on the plane.

All this information was written down and regularly sent by radio to weather centers. After each flight, the weather officer's log was given to forecasters for detailed analysis.

Squadron Operations

Flying Different Missions

The 1st Weather Reconnaissance Squadron operated from various locations across the North Atlantic. They flew four main types of missions:

- Route Reconnaissance: Scouting ahead of planned flights to report weather along a specific path.

- Area Reconnaissance: Flying over large areas to get a general picture of the weather.

- Vertical Soundings: Collecting data at different altitudes.

- Hurricane Reconnaissance: Flying into tropical storms and hurricanes to gather data.

Early Missions and Successes

The first missions in 1943 were route reconnaissance flights using TB-25Ds. The planes would fly ahead of other aircraft, reporting weather using Morse code. At the end of the flight, the weather officer would send a report saying what types of planes could safely cross. To keep information secret from the Germans, all weather reports were encrypted.

Under Clark Hosmer, the squadron divided its nine TB-25Ds into three groups. Each group covered a different part of the Atlantic route. In the first six months of Hosmer's command, the squadron flew 446 missions. Amazingly, no planes were lost due to weather on flights that the squadron had scouted. This was a huge achievement!

Winter Operations and Hurricane Hunting

During the harsh North Atlantic winters, the twin-engine B-25s were sometimes too small for safe flying. So, in December 1943, the squadron received three larger B-17s. These four-engine planes were much better at handling severe winter weather. They flew long "synoptic" tracks, collecting data over wide areas.

In May 1945, a part of the squadron, called Duck Flight, moved to Florida. Their new job was to look for hurricanes. On September 12, they found one of the most powerful hurricanes ever recorded, later known as Kappler's Hurricane.

Second Lieutenant Bernard J. Kappler, a weather officer, spotted the developing hurricane. His B-25 flew right through the storm, which was already near hurricane strength. The next day, they flew back into the storm. Kappler's plane faced winds up to 120 knots (about 138 mph), severe shaking, and heavy rain. They even flew into the calm "eye" of the storm. The storm was huge, about 200 miles wide. While there was a lot of damage on the ground, no aircrew members were lost.

Between June and November 1945, Duck Flight flew into six tropical storms and two hurricanes. They also completed 258 regular weather missions. In December, Duck Flight returned to New Hampshire, and the 1st Weather Reconnaissance Squadron was officially closed.

Squadron Information

Awards and Recognition

The 1st Weather Reconnaissance Squadron received the Service Streamer for the American Theater during World War II. This award recognized their important service between December 7, 1941, and March 2, 1946.

Squadron Insignia

The squadron's patch features a thunderbird. In some Native American cultures, thunderbirds are powerful spirits that control the weather. They are said to create lightning and thunder by flapping their wings. The background of the patch is blue, representing the sky. On the patch, you can also see clouds, raindrops, and a lightning bolt, all related to weather.