Abdullah Öcalan facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Abdullah Öcalan

|

|

|---|---|

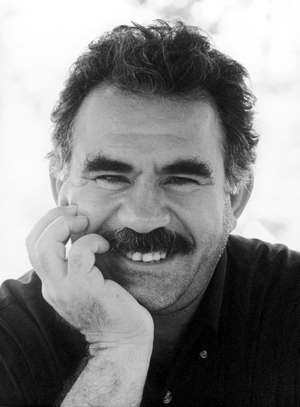

Öcalan in 1997

|

|

| Born | 4 April 1948 or 4 April 1949 Ömerli, Turkey

|

| Nationality | Kurdish and Turkish |

| Education | Faculty of Political Science, Ankara University |

| Spouse(s) |

Kesire Yıldırım

(m. 1978) |

|

Notable ideas

|

Democratic confederalism

Jineology |

Abdullah Öcalan (born 4 April 1948 or 1949), also known as Apo (which means "uncle" in Kurdish), is a founding member of the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK). This group has been involved in a long-standing conflict.

Öcalan lived in Syria from 1979 to 1998. He helped start the PKK in 1978 and led it into conflict in 1984. Syria provided a safe place for the PKK for many years.

After being forced to leave Syria, Öcalan was captured in Nairobi, Kenya, in February 1999. He was then taken to İmralı island in Turkey and put in prison. He was sentenced to life imprisonment. Since 1999, he has been held on İmralı island in the Sea of Marmara.

Öcalan has often called for peaceful ways to solve the conflict. His time in prison has varied, with periods of being completely isolated and times when he was allowed visitors. He was also part of talks with the Turkish government that led to a temporary peace process in 2013. In February 2025, he asked the PKK to stop fighting and break up, which led to the group announcing a ceasefire.

From prison, Öcalan has written several books. One of his ideas is Jineology, which focuses on women's rights and is important to the Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK). Another idea, democratic confederalism, is used in the Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (DAANES), a self-governing area in Syria.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Öcalan was born in Ömerli, a village in southeastern Turkey. His village had a mix of Kurdish, Turkish, and Armenian people living together. Öcalan said his father was Kurdish and his mother was Turkmen. There are no official records of his birth date, but he believes he was born around 1946 or 1947. He was the oldest of seven children. His family was very poor, and he remembered a lot of unhappiness at home.

His younger brother, Osman Öcalan, said their father's family was Kurdish, and their mother's family had mixed Kurdish, Turkish, Arab, and Assyrian roots. The family's surname, Öcalan, means "revengeful" in Turkish. It came from a story where his grandfather fought against Ottoman authorities.

Abdullah Öcalan spoke only Kurdish until he started elementary school in a nearby village. There, he learned Turkish and began to fit in with Turkish culture. He was influenced by the Turkish nationalist school lessons and even dreamed of joining the Turkish army. He tried to get into a military high school but didn't pass the exam.

In 1966, Öcalan went to a vocational high school in Ankara. During this time, he attended both anti-communist and some pro-Kurdish meetings. He didn't start thinking about his Kurdish identity politically until he was almost 20. In his youth, Öcalan was also a very traditional Muslim.

After graduating in 1969, Öcalan worked at the Title Deeds Office in Diyarbakır. This is when his political views started to change. A year later, he moved to Istanbul and joined meetings of the Revolutionary Cultural Eastern Hearths (DDKO), a Kurdish group. He then studied law at Istanbul University before transferring to Ankara University to study political science.

Öcalan was arrested in April 1972 for taking part in a protest. He was held for seven months in prison. In 1973, he helped found the Ankara Democratic Association of Higher Education. In 1975, he published a booklet with others that shared ideas for change in Kurdistan. During meetings in Ankara, Öcalan and his group decided that Kurds needed more rights and began planning for a movement. They spread out into different towns in Turkish Kurdistan to gather supporters. By 1977, the group had over 300 followers.

The Kurdistan Workers' Party

In 1978, Öcalan founded the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK). In July 1979, he went to Syria.

The PKK focused on teaching its members about its ideas. Öcalan believed that having a strong set of beliefs was very important for the group's success. With support from the Syrian government, he set up training camps for the PKK in Lebanon.

In 1984, the PKK began armed actions against government forces. Öcalan tried to bring together different Kurdish groups. He met with Masoud Barzani, a leader of another Kurdish group, to work out differences. In 1988, Öcalan said that the goal was not necessarily to become fully independent from Turkey, but he insisted on Kurdish rights. He suggested that talks should happen to create a federation in Turkey, where Kurds would have more self-rule.

In the early 1990s, Öcalan spoke about wanting a peaceful solution to the conflict. He said that different groups could live independently within the same country if they had equal rights. In 1993, at the request of Turkish president Turgut Özal, Öcalan declared a ceasefire. He extended it to allow for talks with the Turkish government. However, after President Özal died, Turkey stopped the talks, saying it would not negotiate with groups it considered terrorists.

Öcalan continued to meet with politicians from other countries, including Germany and Greece, to discuss peaceful solutions. He promised that the PKK would support a peaceful end to the conflict. Over time, many countries, including the United States and the European Union, listed the PKK as a terrorist organization. Until 1998, Öcalan was based in Syria. However, Turkey pressured Syria to stop supporting the PKK. As a result, the Syrian government made Öcalan leave the country.

Time in Europe

Öcalan left Syria on October 9, 1998. For the next four months, he traveled to several European countries, trying to find a solution for the Kurdish-Turkish conflict. He first went to Russia, where the Russian parliament voted to offer him asylum. He then traveled to Italy, arriving in Rome in November 1998.

In Italy, Öcalan asked for political asylum. Turkey asked Italy to send him back. Italy did not send him to Turkey because Italian law prevents sending someone to a country where they might face the death penalty. Italy also didn't want him to stay, so he left for Russia in January 1999. He then flew to Greece and later tried to go to the Netherlands, but his plane was not allowed to land. He returned to Greece and then flew to Nairobi, Kenya, at the invitation of Greek diplomats.

Capture and Imprisonment

Öcalan was captured in Kenya on February 15, 1999, while on his way to the airport. This was an operation by the Turkish National Intelligence Organization, with help from the CIA. He was then flown back to Turkey.

His capture led to protests by thousands of Kurds around the world. In Germany, Kurds were warned that they could be sent back to Turkey if they continued to protest.

Trial

Öcalan was taken to İmralı island, where he was questioned for 10 days without being able to see his lawyers. A special court was set up on the island to try him. His lawyers had difficulty representing him because they were only allowed short visits, and some visits were canceled. The trial began on May 31, 1999.

Öcalan was accused of serious crimes and was sentenced to death on June 29, 1999. Human rights groups like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch called for a new trial, saying that the first one was not fair. In 2002, Turkey stopped using the death penalty, so Öcalan's sentence was changed to life imprisonment.

In 2005, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) ruled that Turkey had violated some of Öcalan's rights during his arrest and trial. However, Turkish courts refused his request for a new trial.

Prison Conditions

After his capture, Öcalan was the only prisoner held in isolation on İmralı island. Even after his sentence was changed to life imprisonment, he remained the only inmate for many years. More than 1,000 Turkish military personnel were stationed on the island to guard him.

In November 2009, Turkish authorities announced that other prisoners would be moved to İmralı, ending his complete isolation. He was allowed to see them for ten hours a week. This new prison was built after a European group visited the island and raised concerns about his living conditions.

From July 2011 until May 2019, Öcalan's lawyers were not allowed to visit him. They filed hundreds of requests, but all were denied. Kurdish communities have held regular protests to bring attention to his isolation. In October 2012, hundreds of Kurdish political prisoners went on a hunger strike to ask for better prison conditions for Öcalan and the right to use the Kurdish language in education. The hunger strike lasted 68 days until Öcalan asked them to stop.

His lawyers were finally allowed to visit him again in April 2019, and Öcalan met with them on May 2, 2019. On February 27, 2025, Öcalan sent a message from prison asking the PKK to hold a meeting to dissolve itself and give up its weapons. In response, the PKK announced a ceasefire on March 1. After the PKK decided to dissolve itself in May 2025, Öcalan announced the end of the PKK's armed actions against the Turkish state the following month.

Peace Efforts

In November 1998, Öcalan suggested a 7-point peace plan. This plan included stopping attacks on Kurdish villages, allowing refugees to return, giving Kurds more self-rule within Turkey, and recognizing the Kurdish language and culture. In January 1999, he said that the group's struggle should shift from fighting to talking and negotiating. After his capture, Öcalan called for the PKK to stop its attacks and work for a peaceful solution within Turkey.

He also called for a "Truth and Justice Commission" to look into actions by both the PKK and Turkish forces. In March 2005, Öcalan proposed "Democratic Confederalism in Kurdistan." This idea suggested a border-free group of Kurdish regions in Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran. In this area, different laws would apply: EU law, the laws of Turkey/Syria/Iraq/Iran, and Kurdish law. The PKK adopted this idea.

In September 2006, Öcalan asked the PKK to declare a ceasefire and seek peace with Turkey. He said, "The PKK should not use weapons unless it is attacked with the aim of annihilation." He also stressed the importance of a democratic union between Turks and Kurds. He worked on a plan for peace that would involve more local control and democracy in Turkey, but his detailed proposal was taken by Turkish authorities in August 2009.

In January 2013, peace talks began between the PKK and the Turkish Government. Öcalan met several times with politicians on İmralı Island. On March 21, Öcalan declared a ceasefire between the PKK and the Turkish state. He said, "Let guns be silenced and politics dominate... It's the start of a new era." The PKK leadership agreed to the ceasefire. During this peace process, a pro-Kurdish political party entered the Turkish parliament in June 2015. However, the ceasefire ended in July 2015 after two Turkish police officers were killed.

New Political Ideas

Since being in prison, Öcalan has changed his political thinking. He has been influenced by Western thinkers like Murray Bookchin. He moved away from his earlier beliefs and developed a new idea called democratic confederalism. In early 2004, Öcalan tried to meet with Murray Bookchin, calling himself Bookchin's "student."

Democratic Confederalism

Democratic confederalism is a system where local communities have control over their own areas through elected councils. These local groups then connect with others through a network of larger councils. Decisions are made by small groups in each neighborhood, village, or city. Everyone is welcome to join these local councils. In this system, there is no private property in the usual sense; instead, people have the right to use buildings, land, and resources, but not to buy or sell them for profit. The economy is managed by the local councils. Important parts of democratic confederalism are feminism (equality for women), caring for the ecology (environment), and direct democracy (where people directly make decisions).

With his 2005 "Declaration of Democratic Confederalism in Kurdistan," Öcalan suggested that Kurds could use Bookchin's ideas to create a democratic group of Kurdish communities that would go beyond the borders of Syria, Iran, Iraq, and Turkey. Öcalan promoted shared values like protecting the environment, self-defense, gender equality, and accepting different religions, politics, and cultures. The PKK adopted Öcalan's ideas and began to form these local groups. This idea also became important for the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and is used in the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES).

On Women's Rights

Öcalan strongly supports the freedom of women. He believes that all forms of slavery are connected to the traditional role of women as housewives. He thinks that women are often stuck in situations where they accept old-fashioned gender roles and unequal relationships with men.

Personal Life

During Öcalan's childhood, his mother was a strong figure who often criticized his father for their financial struggles. He later said that he learned to defend himself from unfairness during his childhood. Like many Kurds in Turkey, Öcalan grew up speaking Turkish. Some sources say he didn't know Kurdish when he was older. In 1978, Öcalan married Kesire Yildirim, whom he met at Ankara University. Their marriage was reportedly difficult.

Öcalan felt regret after his sister Havva had an arranged marriage. This event influenced his ideas about freeing women from traditional roles. Öcalan's brother, Osman, was a PKK commander but later left the group. His other brother, Mehmet Öcalan, is a member of a pro-Kurdish political party. His niece, Dilek Öcalan, was a parliamentarian, and his nephew, Ömer Öcalan, is currently a member of parliament.

Honorary Citizenships

Several towns have given Öcalan honorary citizenship:

- Palermo

- Olympia

- Naples

- Castel del Giudice

- Castelbottaccio

- Pinerolo

- Martano

- Reggio Emilia

- Palagonia

- Riace

- Berceto

- Fossalto

See also

In Spanish: Abdullah Öcalan para niños

In Spanish: Abdullah Öcalan para niños