Abraham Ulrikab facts for kids

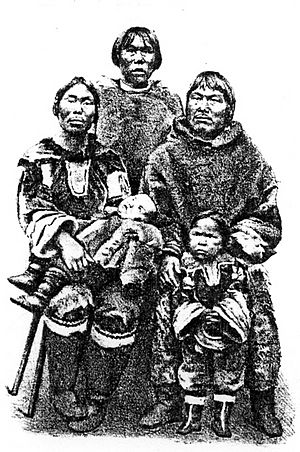

Abraham Ulrikab (born January 29, 1845 – died January 13, 1881) was an Inuk man from Hebron, Labrador, in Canada. He, along with his family and four other Inuit, agreed to travel to Europe. They were part of special cultural shows organized by Carl Hagenbeck, who owned a zoo in Hamburg, Germany.

Contents

How Names Worked Back Then

Before 1893, Inuit in northern Labrador didn't use family names that passed down from fathers. Instead, married couples often used their spouse's first name with "-b" or "-ib" added to it. For example, Abraham's last name might have been "Ulrikeb" because his wife's name was Ulrike. This meant Ulrike's full name was probably "Ulrike Abrahamib." Children would take the last name of the parent of the opposite gender before they got married. So, their daughters, Sara and Maria, were likely named "Sara Ulrikeb" and "Maria Ulrikeb."

The Inuit Travel to Europe (September 1880–January 1881)

Eight Inuit people, from two families, went to Europe. Here were their approximate ages when they arrived:

- The Christian family:

- Abraham, 35 years old

- Ulrike, 24, his wife

- Sara, 3 and a half, their daughter

- Maria, 10 months old, their baby daughter

- Tobias, 20, a young unmarried man

- The non-Christian family:

- Tigianniak, about 45, the father

- Paingu, around 50, his wife

- Nuggasak, their teenage daughter, about 15

Abraham was special because he could read and write. He was also a talented violin player and a strong Christian. He naturally became the leader of the group. Even though missionaries tried to stop him, Abraham decided to go to Europe. He hoped the money he earned would help him pay off debts to the Moravian mission store in Hebron. He was also curious to see Europe and meet some of the missionaries he knew. But soon after they arrived, the Inuit realized they had made a big mistake. They missed Labrador and wanted to go home.

On August 26, 1880, all eight Inuit boarded a ship called the Eisbär (which means "polar bear" in German). They sailed to Europe and arrived in Hamburg on September 24, 1880. Their show at Hagenbeck's zoo opened on October 2, 1880. On October 15, the group moved to Berlin. They were shown at the Berlin zoo until November 14. After that, they traveled to Prague, then Frankfurt, and Darmstadt.

Sadly, Nuggasak died suddenly on December 14. The group then moved to Crefeld, where Paingu died on December 27. It was only when little Sara started showing symptoms that doctors finally figured out what was making the Inuit sick: smallpox. Abraham and Ulrike were heartbroken. They had to leave Sara at the hospital in Krefeld because the group had to go to their next stop, Paris. Sara died on December 31, 1880, just as her parents reached Paris.

The five people who were left got vaccinated against smallpox on January 1, 1881. But it was too late. The group was shown at the Jardin d'Acclimation in Paris for about a week. Then, on January 9, 1881, they were taken to Hôpital Saint-Louis. All of them died within the next week. Maria died on January 10, 1881. Tigianniak died on January 11. Tobias and Abraham died on January 13. Ulrike, the last one, died on January 16, 1881.

The person who hired them, Johan Adrian Jacobsen, had forgotten to make sure they got vaccinated against smallpox. This was even required by German law. In his diary, Jacobsen admitted he had forgotten.

Abraham's Diary

During his travels in Europe, Abraham wrote a diary in his own language, Inuktitut. After he died, the diary was sent back to his family in Hebron.

In Hebron, a missionary named Carl Gottlieb Kretschmer translated Abraham's diary into German. This was the same missionary who had tried to stop the Inuit from going to Europe. Later, English and French versions were also published. But then, the story was mostly forgotten for about 100 years.

In 1980, Abraham's diary was found again. A Canadian expert named Dr. James Garth Taylor discovered a copy of the German translation. He found it in the archives of the Moravian Church in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Dr. Taylor wrote an article in 1981, and that's how the story of the eight Labrador Inuit became known to people in the 20th century.

Over the next 25 years, more people studied this sad story. This included a German expert named Hilke Thode-Arora and Professor Hartmut Lutz with his students. They used Abraham's diary along with information from old newspapers and archives.

In 2005, a book called The Diary of Abraham Ulrikab: Text and Context was published. This book finally put Abraham's diary into print. It made sure that his words and his story would reach the Labrador Inuit people of today.

Abraham's diary is very important. It is the only known story from the point of view of someone who was part of Carl Hagenbeck's "human zoos." It is also one of the first autobiographies written by an Inuk person. Sadly, Abraham's original diary, written in Inuktitut, has not been found yet.

Finding the Inuit's Remains

In 2009, a French-Canadian woman named France Rivet learned about Abraham's story. She read the book The Diary of Abraham Ulrikab: Text and Context. She wondered what had happened to the Inuit in Paris and what became of their bodies. She promised to look into it. About a year into her research, she found documents. These documents showed that anthropologists in Paris had studied Paingu's skull and made plaster molds of the brains of Abraham, Ulrike, and Tobias.

She wondered if these items were still in a museum. She sent letters to ask. Soon, she got a reply from the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle:

Mrs. Rivet, we are sorry to tell you that we do not have the brain molds. But we do have the skullcap and the full skeletons of the five Labrador Inuit who died in Paris in January 1881.

This news was completely unexpected! It started a four-year search to find out everything about the Inuit's story. It also led to talks with leaders in Nunatsiavut, Canada, and France. The goal was to prepare for the possible return of the remains home.

Bringing the Inuit's Remains Home

In the fall of 2014, a book called In the Footsteps of Abraham Ulrikab was published. This book shared the results of the research and announced that the Inuit's remains had been found. The skeletons of Abraham, his wife Ulrike, their daughter Maria, young Tobias, and Tigianniak were found. They were in the collections of the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle in Paris. Paingu's skullcap, which had been taken during her autopsy in Krefeld, is also in the museum's collection. Finally, Sara's skull was found in Berlin.

The museum's director, Michel Guiraud, has said they are ready to return the remains to the Labrador Inuit. On June 14, 2013, Canada and France signed an agreement. They confirmed they would help bring the Inuit bones from French museums back to Canada.

The leaders and people of Nunatsiavut have started thinking about whether the remains should be brought back to Canada. In the summer of 2015, the Nunatsiavut Government began asking people for their opinions. They are working on a plan for bringing human remains and old objects from archaeological sites in Nunatsiavut back home.

Film About Abraham Ulrikab

A documentary film, Trapped in a Human Zoo: Based on Abraham's Diary, was shown in February 2016. It told Abraham's story, the search for his remains, and the Labrador Inuit's efforts to bring them home. It aired on CBC Television's The Nature of Things. This film was made by Pix3 Films. In 2017, the documentary was nominated for two awards.

See also

- List of people of Newfoundland and Labrador

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |