Albert Brewer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Albert Brewer

|

|

|---|---|

Brewer in 1967

|

|

| 47th Governor of Alabama | |

| In office May 7, 1968 – January 18, 1971 |

|

| Lieutenant | Vacant |

| Preceded by | Lurleen Wallace |

| Succeeded by | George Wallace |

| 21st Lieutenant Governor of Alabama | |

| In office January 16, 1967 – May 7, 1968 |

|

| Governor | Lurleen Wallace |

| Preceded by | James Allen |

| Succeeded by | Jere Beasley |

| Speaker of the Alabama House of Representatives | |

| In office January 1963 – January 1967 |

|

| Preceded by | Roberts H. Brown |

| Succeeded by | Hugh G. Merrill |

| Member of the Alabama House of Representatives from Morgan County, Seat 1 | |

| In office January 1955 – January 1967 |

|

| Preceded by | Noble Russell |

| Succeeded by | Leslie Doss |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Albert Preston Brewer

October 26, 1928 Bethel Springs, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | January 2, 2017 (aged 88) Montgomery, Alabama, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Martha Farmer (1950–2006) |

| Education | University of Alabama (BA, LLB) |

| Signature |  |

Albert Preston Brewer (October 26, 1928 – January 2, 2017) was an American lawyer and politician. He was a member of the Democratic Party. Brewer served as the 47th governor of Alabama from 1968 to 1971.

Before becoming governor, he held several important positions in Alabama. He was the Lieutenant Governor of Alabama, the leader (called the Speaker) of the Alabama House of Representatives, and a state representative for Morgan County from 1955 to 1967.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Albert Preston Brewer was born on October 26, 1928, in Bethel Springs, Tennessee, in the United States. His parents were Daniel A. Brewer, a farmer, and Clara Albert Brewer. When Albert was a child, his family moved to Decatur. This move allowed his father to work for the Tennessee Valley Authority, which was a government agency.

Albert attended local schools in Decatur, including Lafayette Street School, Decatur Jr. High School, and Decatur High School. In 1946, he went to the University of Alabama to study history and political science. He later earned his law degree from the University of Alabama School of Law in 1952. After finishing his studies, he returned to Decatur to work as a lawyer. From 1956 to 1963, he led the Decatur Planning Commission. In 1963, he was recognized as Decatur's "Outstanding Young Man of the Year." He was also chosen as one of the four "Outstanding Young Men in Alabama" by the Alabama Junior Chamber of Commerce.

Brewer married Martha Helen Farmer in 1950. They had two daughters named Rebecca Anne and Beverly Allison. He was a Baptist.

Political Career

Serving in the House of Representatives

In 1953, Albert Brewer led a group called the "Young Democrats" in his area. The next year, the person representing Morgan County in the Alabama House of Representatives decided to retire. Local leaders asked Brewer to run for the position. He won the Democratic primary election easily and had no opponents in the main election. He took his seat in the House the following year. He was reelected two more times, in 1958 and 1962.

In 1963, with the support of the new Governor, George Wallace, Brewer was chosen as the Speaker of the House. This meant he was the leader of the Alabama House of Representatives. As Speaker, he also became the chairman of the House Rules Committee. Under Brewer's leadership, the House generally supported Governor Wallace's plans. During this time, a bill was passed to increase money for education, which also meant new taxes. Brewer had some concerns about this because Wallace had promised not to raise taxes.

In 1964, Brewer and James B. Allen, who was the lieutenant governor at the time, were on the ballot as unpledged presidential electors for Alabama. They were not committed to any specific presidential candidate. They lost to the Republican electors who supported Barry M. Goldwater.

Becoming Lieutenant Governor

In 1966, Brewer thought about running for governor. However, the current Governor, George Wallace, could not run again because of state rules. Instead, Governor Wallace's wife, Lurleen Wallace, decided to run. Brewer realized it would be hard to win against her, so he chose to run for lieutenant governor of Alabama instead. He won the Democratic primary election by a large margin and had no opposition in the general election. He was sworn into office on January 16, 1967. Lurleen Wallace also won the governor's race. As lieutenant governor, Brewer convinced the state legislature to create a group called the Education Study Commission. This group would look into ways to improve schools.

In July 1967, Governor Lurleen Wallace went to Texas for cancer treatment. Alabama law stated that if the governor was out of the state for 21 days, the lieutenant governor would temporarily take over as acting governor. This happened on July 24, and Brewer served as acting governor for about 15 hours. During this time, he met with state officials, signed some papers, and appointed 25 honorary colonels. Governor Wallace was then flown back to Alabama.

Serving as Governor

Taking Office

Albert Brewer knew that Governor Lurleen Wallace was sick with cancer, but he didn't realize how serious it was until shortly before she passed away. Governor Wallace died on May 7, 1968. According to the state constitution, Brewer then became the new governor. He took his oath of office quietly, with only his family and George Wallace present. Brewer was careful not to show his feelings or views too much at first. He even waited to move into the governor's mansion until George Wallace had found a new home for his family.

Brewer decided to keep most of the people who worked in the governor's cabinet. However, he did replace the public safety director and the director of the Department of Conservation. This was because they refused to offer their resignations, and the latter even had a physical fight with another state employee.

Soon after becoming governor, Brewer and his new finance director, Bob Ingram, found that the previous administration had often favored certain supporters in state business. Brewer was bothered by these issues. He wanted to be elected governor in his own right in 1970, so he felt it was best not to openly criticize George Wallace's supporters. To fix things quietly, Brewer and Ingram chose experienced and ethical public servants for important roles. While Brewer sometimes helped friends with jobs or favors, his administration was generally more fair than those before him. State workers felt better about their jobs during his time.

Unlike the two governors before him, Brewer held weekly press conferences. In June 1968, he announced that he would create a state motor pool by executive order. This system would help stop people from using state vehicles for personal reasons. All state vehicles had to be checked out, and fuel had to be bought from the state. He also put state symbols on all motor pool vehicles so they were clearly government property. About 1,000 unnecessary vehicles were sold, including the governor's limousine. These changes saved the government a small amount of money. He also sold extra copy machines, combined the state's computer systems, and cut 12 senior assistant jobs.

George Wallace criticized some of Brewer's changes, especially the motor pool. He felt they were a criticism of his late wife. At first, Brewer was careful not to upset the Wallaces. But their complaints annoyed him, and he stopped worrying about it. Brewer also started an investigation into money collected by agents of the Alcohol Beverage Control Board. Even though a law in 1963 had stopped this practice, many agents were still collecting money without permission. George Wallace said he didn't know about this, and Brewer agreed he was innocent. However, Wallace still criticized Brewer for the public attention the issue received.

After some scandals in the state legislature, Brewer created an ethics commission. This group was asked to write a code of ethics for state officials. Brewer suggested rules like not allowing gifts for officials, banning officials from working for companies they regulated, and requiring them to tell if they had a conflict of interest. He used money from his own office budget to support this commission's work.

To help Alabama's economy grow, Brewer worked to attract new industries. He traveled to New York to talk with company leaders and met with many business representatives. He also created the Alabama Program Development Office. This office helped local governments get federal money for development projects. After several major fish kills in state rivers caused by chemical dumping, Brewer pushed the state to take action against Geigy Chemical Company and create new laws to prevent pollution.

Working with the Legislature

When there were disagreements about laws or policies, Governor Brewer preferred to talk things out and find common ground. This was different from George Wallace, who often used public arguments or favors to get his way. Before the first legislative session during his time as governor, Brewer decided to focus on improving education. He also wanted to make government procedures simpler, cut unnecessary spending, and improve Alabama's image across the country.

He looked into the state of education in Alabama and found that the school system was not getting better compared to other states. This was true even after efforts to improve it during the Wallace administrations. Brewer told state education officials that he wanted to change how Alabama dealt with federal orders to end school segregation. Unlike Wallace, who was openly against these orders, Brewer wanted to "try to do it in a way that will let us do the most palatable thing for the people."

Brewer believed that a school choice policy, which allowed integrated schools, could meet the federal government's demands and be accepted by most Alabamians. This would help him achieve his goal of improving public education. However, many federal courts were not happy with such proposals because some people used school choice to try and keep schools segregated. A few weeks after Brewer told President Lyndon B. Johnson that he would work with the federal government on school segregation, the United States Attorney General sued to stop school choice options. After the court ordered new steps for integration, President Johnson ordered schools to integrate their teachers at a specific ratio and close some black schools. Brewer responded by using similar language as those who supported segregation. He complained about government interference. He also warned that if schools were forced to integrate more directly, most white parents would send their children to private schools. Despite this, he promised to follow any court orders about racial issues. His request for President Johnson to reconsider his order was denied.

Meanwhile, the Education Study Commission released a report about education in Alabama. It showed many problems, such as overcrowded schools, not enough learning materials, teachers who weren't fully qualified, and low pay for teachers. The commission said that more money was needed to fix these issues. In 1969, Brewer called the legislature into a special meeting to consider 30 bills aimed at improving education. Even though some lawmakers from cities thought the plan helped rural areas more, the proposals passed. They increased education spending by $132 million and raised teacher salaries by over 20 percent in two years. The laws also made the state and local superintendent positions appointed instead of elected. They gave the Education Study Commission official legal status and created the Alabama Commission on Higher Education.

At the start of the 1969 session, Brewer announced he would push for new pollution control laws. However, powerful industry groups lobbied the legislature heavily, and only a weak bill was passed. Brewer was more focused on education reform. He decided not to push for stronger pollution rules because it would upset businesses and, in his view, wouldn't help him get more votes in the 1970 election. More fish kills and serious mercury pollution in 1970 led Brewer to ask for federal help and order a water quality survey. As his term was ending, he briefly thought about calling a special session to address pollution but decided it wasn't possible. His efforts in 1969 to strengthen consumer credit protections or have the legislature meet every year (instead of every two years) also failed. Despite these setbacks, Brewer's administration did get funding for a state Medicaid program, a pay raise for state employees, new highway safety laws, a meat inspection law, and a rule that all workers hired by the state for construction must be paid standard wages.

1970 Governor Election Campaign

Brewer supported George Wallace's 1968 presidential campaign. He helped raise money and gave speeches for him. Within months of Brewer becoming governor, Wallace privately told him and publicly stated that he would not run for governor in 1970. Brewer continued to prepare to be elected governor in his own right in 1970. He took bolder policy positions, keeping in mind that Wallace might still decide to run.

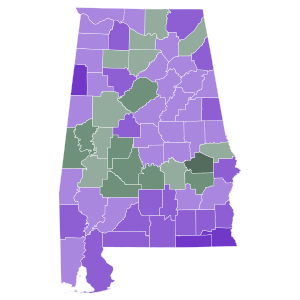

In this effort, Brewer gained an important ally in U.S. President Richard M. Nixon. Nixon had defeated Wallace in the 1968 presidential election. Nixon wanted to make sure Wallace wouldn't be a problem for him in the 1972 presidential election. Brewer's 1970 campaign for governor was new in many ways. While he had been seen as someone who supported segregation earlier in his career, Brewer refused to use racist language in this campaign. He actively sought out newly registered black voters. He hoped to bring together black people, educated middle-class white people, and working-class white people from northern Alabama, which was a more liberal part of the state.

Brewer presented a plan that called for more money for education. He also wanted an ethics commission and a group to update Alabama's 1901 state constitution. This old constitution had been designed to prevent black people and poor white people from voting.

Brewer led Wallace in the first round of the Democratic primary election but didn't win enough votes to be the clear winner. So, he faced Wallace in a second election, called a runoff. Wallace, whose hopes for becoming president would have ended if he lost, ran a very aggressive campaign. He used strong messages that appealed to some voters. Wallace called Brewer names and promised not to run for president a third time. Wallace narrowly won the Democratic runoff election with 51.6 percent of the vote, while Brewer received 48.4 percent. Wallace then won the general election by a large amount. Brewer was succeeded by Wallace on January 18, 1971, after serving 987 days as governor.

Later Life

After leaving the governor's office in 1970, Brewer joined a law firm in Montgomery. He thought about running against Wallace again in the 1974 governor's election. He hoped that racial issues would be less important by then. However, he decided against it because Wallace remained very popular, even after being shot in 1972.

Instead, Brewer ran for governor again in 1978. But he lost the Democratic primary election and didn't make it to the runoff by a small number of votes. When Wallace ran for governor again in 1982, Brewer supported the Republican candidate, Emory Folmar, in the main election. In 1987, Brewer became a professor of law and government at Samford University's Cumberland School of Law. Before he passed away, he taught a course on Professional Responsibility at the Cumberland School of Law. He was also an active leader with the Alabama Citizens for Constitutional Reform since 2000.

Albert Brewer died on January 2, 2017, at Jackson Hospital in Montgomery, Alabama. He was 88 years old.

Legacy

Albert P. Brewer High School in eastern Morgan County is named after Albert Brewer. The school opened in 1972.

Historian Gordon E. Harvey wrote that "Brewer did more to improve education in Alabama than most of his predecessors and all but a few of his successors."

See Also

- List of Governors of Alabama

- Lieutenant Governor of Alabama

- Alabama House of Representatives