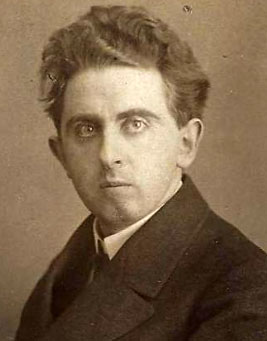

Albert Ehrenstein facts for kids

Albert Ehrenstein (born December 23, 1886 – died April 8, 1950) was a poet from Austria. He was part of a movement called Expressionism, which focused on showing strong feelings and ideas. Albert Ehrenstein's poems often showed that he didn't like traditional, middle-class ways of life. He was also very interested in the East, especially China.

He lived most of his life in Berlin, Germany. But he also traveled a lot! He visited places across Europe, Africa, and the Far East (like China). In 1930, he went to Palestine and wrote articles about what he saw. Just before the Nazis took power in Germany, Ehrenstein moved to Switzerland. Later, in 1941, he moved to New York City, USA, where he passed away.

Contents

Albert Ehrenstein's Early Life

Albert Ehrenstein was born in Ottakring, Vienna, Austria. His parents were Jewish and from Hungary. His father worked as a cashier at a brewery, and his family was not rich. His younger brother, Carl Ehrenstein, also became a poet.

Albert's mother helped him go to high school. There, he faced bullying because he was Jewish. From 1905 to 1910, he studied history and philosophy in Vienna. He earned a doctorate degree in 1910, writing his main paper about Hungary in 1790. He had already decided he wanted to be a writer. He said that his five years of study mostly gave him the freedom and time to write poetry.

His Poetry and Writing Career

In 1910, Albert Ehrenstein wrote a poem called "Wanderers song." It was published by Karl Kraus in a magazine called Overnight Torch. This poem is seen as an early example of Expressionism. In 1911, the poem was published again with drawings by his friend, Oskar Kokoschka.

Through Kokoschka, Ehrenstein met Herwarth Walden. His work then appeared in Walden's magazine, Der Sturm. Later, his writings were also published in Franz Pfemfert's magazine, Die Aktion. Ehrenstein quickly became one of the most important writers in the Expressionist movement. He became close friends with other famous writers like Else Lasker-Schüler, Gottfried Benn, and Franz Werfel.

Ehrenstein and World War I

When World War I began, Albert Ehrenstein was not allowed to join the military. Instead, he was told to work in the Vienna War Archives. Many artists at the time were excited about the war at first. However, Ehrenstein was against the war from the very beginning. He clearly showed his feelings in many articles and poems, including a collection called The man screams.

During the war, he met writers like Walter Hasenclever and Martin Buber. From 1916 to 1917, he was part of the group that created the first Dadaist magazine, The New Youth. He published his work there alongside Franz Jung, George Grosz, and Johannes R. Becher. This magazine was strongly against the German Emperor Wilhelm II and was quickly banned. Becher and Ehrenstein also worked as editors for the publisher Kurt Wolff. After 1918, Ehrenstein supported the revolution in Germany. He signed a statement with others, including Franz Pfemfert, against nationalism.

Travels and Later Works

During the war, Ehrenstein also met the actress Elisabeth Bergner. He helped her become successful in her career. He fell deeply in love with her and wrote many poems for her.

In the 1920s, he traveled with his friend Kokoschka across Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and China. He stayed in China for some time. He became very interested in Chinese literature. He wrote many new versions of Chinese stories and poems. He also wrote a successful novel called Murderer from Justice (1931). By the end of 1932, Ehrenstein moved to Brissago, Switzerland.

Life as a Refugee

The Nazi party in Germany made a list of authors they didn't like, and Albert Ehrenstein was on it. On May 10, 1933, his books were among those burned in public. For the next few years, he published his writings in magazines outside of Germany.

In 1934, he traveled to the Soviet Union. In 1935, he went to Paris, France, for a meeting called the "Congress for the Defense of Culture." In Switzerland, he was in danger of being sent back to Germany because he was a foreigner. Hermann Hesse, another famous writer, tried to help him get permanent safety in Switzerland. He only managed to get Ehrenstein temporary papers to stay. To avoid being sent back to Germany, Ehrenstein got citizenship from Czechoslovakia.

He then went to England to stay with his brother Carl. After that, he moved to France. Finally, in 1941, he was able to leave Europe for Spain and then travel to the United States.

Later Life and Death

In New York City, Albert Ehrenstein met other people who had also left Germany, like Thomas Mann, Richard Huelsenbeck, and George Grosz. He was allowed to live in the United States. Ehrenstein learned English, but he found it hard to get a job. He lived on money he earned from writing articles for newspapers and on loans from his friend George Grosz.

In 1949, he went back to Switzerland, and then to Germany. However, he couldn't get his work published there. Disappointed, he returned to New York. After two years, he was placed in a hospice for people who were poor, where he died on April 8, 1950. After he passed away, his friends collected money to send his ashes to England, where his brother Carl still lived. His urn was finally buried in the Bromley Hill Cemetery in London.

Albert Ehrenstein's Legacy

Years after his death, Albert Ehrenstein's writings and life story were recorded at the National Library of Israel. His ashes were later re-buried there as well. During his life, he had a big impact on many writers of the 20th century and was friends with many of them.

Selected Works

Poetry and Essays

- Tubutsch, 1911 (changed edition 1914, many new editions)

- Der Selbstmord eines Katers, 1912

- Die weiße Zeit, 1914

- Der Mensch schreit, 1916

- Nicht da nicht dort, 1916

- Die rote Zeit, 1917

- Den ermordeten Brüdern, 1919

- Karl Kraus 1920

- Die Nacht wird. Gedichte und Erzählungen, 1920 (Collection of older works)

- Der ewige Olymp. Novellen und Gedichte, 1921 (Collection of older works)

- Wien, 1921

- Die Heimkehr des Falken, 1921 (Collection of older works)

- Briefe an Gott. Gedichte in Prosa, 1922

- Herbst, 1923

- Menschen und Affen, 1926 (Collection of essays)

- Ritter des Todes. Die Erzählungen von 1900 bis 1919, 1926

- Mein Lied. Gedichte 1900–1931, 1931

- Gedichte und Prosa. Edited by Karl Otten. Neuwied, Luchterhand 1961

- Ausgewählte Aufsätze. Edited by M. Y. Ben-gavriêl. Heidelberg, L. Schneider 1961

- Todrot. Eine Auswahl an Gedichten. Berlin, hochroth Verlag 2009

Translations and Adaptations

- Schi-King. New versions of Chinese poetry, 1922

- Pe-Lo-Thien. New versions of Chinese poetry, 1923

- China klagt. New versions of revolutionary Chinese poetry from three millennia 1924; new edition AutorenEdition, Munich 1981 ISBN: 3761081111

- Lukian, 1925

- Räuber und Soldaten. Novel freely adapted from Chinese, 1927; new edition 1963

- Mörder aus Gerechtigkeit, 1931

- Das gelbe Lied. New versions of Chinese poetry, 1933

Literature

- ; (full text online)

- A. Ehrenstein. Reading as part of the Vienna Festival 1993 Edited by Werner Herbst & Gerhard Jaschke. (Series: Forgotten Authors of Modernism 67) Universitätsverlag Siegen, 1996 ISSN 0177-9869

- Stefan Zweig: "Albert Ehrensteins Gedichte", in: Rezensionen 1902–1939. Encounters with Books. 1983 (E-Text)

See also

In Spanish: Albert Ehrenstein para niños

In Spanish: Albert Ehrenstein para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |