Karl Kraus (writer) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Karl Kraus

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 28 April 1874 Jičín, Kingdom of Bohemia, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | June 12, 1936 (aged 62) Vienna, Austria |

| Occupation |

|

| Education | University of Vienna |

| Genre | Satire |

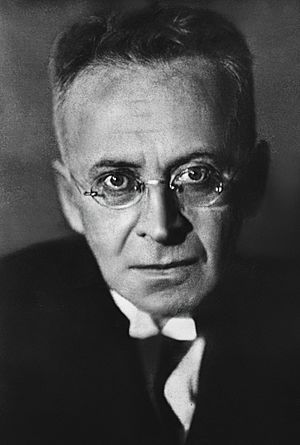

Karl Kraus (born April 28, 1874 – died June 12, 1936) was an Austrian writer and journalist. He was famous for his sharp wit and for writing satire, essays, and poems. He often used his writing to criticize the newspapers, German culture, and the politics of Germany and Austria. He was even nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature three times!

Biography

Early Life and Education

Karl Kraus was born into a wealthy Jewish family in Jičín, which was then part of Austria-Hungary (now the Czech Republic). His father, Jacob Kraus, was a papermaker. In 1877, when Karl was three years old, his family moved to Vienna.

In 1892, Karl started studying law at the University of Vienna. Around the same time, he began writing for a newspaper called Wiener Literaturzeitung. He also tried acting in a small theater but it didn't work out. In 1894, he changed his studies to philosophy and German literature, but he left the university in 1896 without finishing his degree.

Starting His Career

Before 1900: Finding His Voice

In 1896, Kraus decided to focus on writing and performing. He joined a group of young writers in Vienna. However, he soon broke away from them, criticizing their work in a sharp satire called Demolished Literature. He also became a writer for the Breslauer Zeitung newspaper.

Kraus strongly believed that Jewish people should fit into society. Because of this, in 1898, he criticized Theodor Herzl, who started modern Zionism (a movement to create a Jewish homeland). Kraus wrote a strong article called A Crown for Zion. The title was a clever play on words, as "Krone" meant both "crown" and the money used in Austria-Hungary at the time.

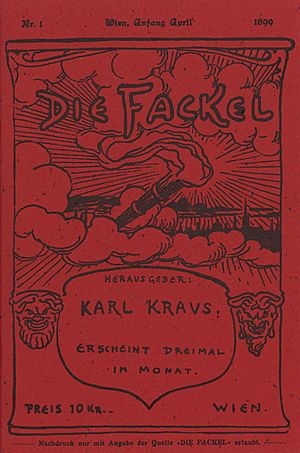

On April 1, 1899, Kraus officially left the Jewish faith. In the same year, he started his own newspaper, Die Fackel (The Torch). He ran, published, and wrote for Die Fackel until he died. Through this newspaper, he attacked many things he saw as wrong, like hypocrisy (people pretending to be better than they are), the ideas of psychoanalysis, corruption in the Habsburg empire, and extreme nationalism.

1900–1909: Die Fackel Grows

In 1901, Kraus faced lawsuits from people who felt he had attacked them in Die Fackel. Many more lawsuits followed over the years because of his strong opinions.

Die Fackel became very special because Kraus was financially independent. This meant he could print whatever he wanted, making it a truly independent magazine. In its early years, famous writers and artists contributed to it. However, after 1911, Kraus usually wrote the entire newspaper himself. He published almost all of his work in Die Fackel, with 922 issues appearing in total.

Die Fackel focused on exposing corruption, criticizing journalists, and calling out bad behavior. Kraus often targeted powerful figures like newspaper owners and politicians.

In 1902, Kraus published a book called Morality and Criminal Justice. He also started publishing his short, wise sayings, called aphorisms, in Die Fackel. These were later collected in a book called Sayings and Gainsayings in 1909.

Besides his writing, Kraus was known for his popular public readings. Between 1892 and 1936, he gave about 700 one-man shows. He would read from plays by famous writers like William Shakespeare and even perform operettas, singing all the parts himself! These readings were very popular, sometimes attracting four thousand people. His magazine also sold forty thousand copies at its peak.

1910–1919: War and Masterpiece

After 1911, Kraus became the main writer for most issues of Die Fackel. He was very skilled at using clever wordplay with quotes to make his points.

When Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria was killed in 1914, leading to World War I, Die Fackel stopped publishing for several months. When it returned in December 1914, Kraus wrote against the war. Censors often tried to stop or take away copies of Die Fackel because of his anti-war views.

Kraus's most famous work is a huge satirical play about World War I called The Last Days of Mankind. It mixes real conversations from that time with imaginary, end-of-the-world scenes. He started writing it in 1915 and published it in parts in Die Fackel in 1919. This play is seen as a very important work, even though Kraus's changing views during the war made it a bit uneven.

In 1919, he also published his collected war writings under the title World Court of Justice.

1920–1936: Later Years and Legacy

In 1924, Kraus started a public fight against Imre Békessy, a tabloid newspaper publisher. Kraus accused Békessy of trying to get money from restaurant owners by threatening them with bad reviews. Békessy fought back, but Kraus launched a strong campaign against him, shouting "Throw the scoundrel out of Vienna!" Békessy eventually fled Vienna in 1926 to avoid arrest.

A major moment in Kraus's political involvement was his strong criticism in 1927 of Johann Schober, the powerful Vienna police chief. This happened after 89 rioters were shot by police during the July Revolt of 1927. Kraus put up posters all over Vienna with a single sentence demanding Schober's resignation. This poster is now a famous symbol of Austrian history.

In 1928, Kraus published a play called The Insurmountables, which included references to his fights with Békessy and Schober. He also translated William Shakespeare's sonnets in 1932.

Kraus supported the Social Democratic Party of Austria in the 1920s. Later, in 1934, he supported Engelbert Dollfuss's government takeover, hoping it would stop Nazism from spreading into Austria. This decision caused some of his followers to disagree with him.

In 1933, Kraus began writing The Third Walpurgis Night, a satire about Nazi ideas. He didn't publish it fully at first to protect his friends who lived in Nazi Germany. He famously started this work with the sentence, "Mir fällt zu Hitler nichts ein" ("Hitler brings nothing to my mind"). The last issue of Die Fackel appeared in February 1936.

Shortly after, Kraus had an accident with a bicyclist, which caused him severe headaches and memory loss. He gave his last public reading in April and had a serious heart attack in June. He died in his apartment in Vienna on June 12, 1936, and was buried in the Zentralfriedhof cemetery.

Karl Kraus never married, but he had a close, though sometimes difficult, relationship with Baroness Sidonie Nádherná von Borutín from 1913 until his death. Many of his works were written at her family's castle.

In 1911, Kraus became a Catholic. However, in 1923, he left the Catholic Church because he was disappointed by its support for the war.

Kraus was also known for his strong opinions on Sigmund Freud and psychoanalysis. Some people say he was a harsh critic, while others argue that he respected Freud but had some concerns.

Character

Karl Kraus was a person who caused a lot of discussion throughout his life. Some people called him "vain" or "self-important." But his followers saw him as a wise leader who would do anything to help those he supported. Kraus believed that future generations would be his most important audience.

Language was extremely important to Kraus. He thought that people's careless use of words showed that they didn't care enough about the world. A composer named Ernst Krenek once described meeting Kraus in 1932, when people were worried about the bombing of Shanghai. Kraus was focused on fixing a comma in his writing. He said, "I know that everything is pointless when the house is burning. But I have to do this, as long as it is at all possible; for if those who were supposed to look after commas had always made sure they were in the right place, Shanghai would not be burning." This shows how much he believed in the power and importance of precise language.

The Austrian writer Stefan Zweig called Kraus "the master of venomous ridicule" because of his sharp and biting humor. Before 1930, Kraus mostly aimed his satire at people in the middle or left of politics, believing that the flaws of the right were too obvious to comment on. Later, he strongly criticized the Nazis.

To his many enemies, however, he seemed like a bitter person who disliked everyone. He was accused of being full of hate. Along with Karl Valentin, he is considered a master of "gallows humor" – a type of dark, ironic humor.

Many people admired Kraus. Writer Gregor von Rezzori said that Kraus's life was an example of strong morals and courage for anyone who writes. He described Kraus's face lighting up with a "fanatic love for the miracle of the German language" and a "holy hatred for those who used it badly."

The writer Bertolt Brecht said of Kraus, "As the epoch raised its hand to end its own life, he was the hand." This means that Kraus was a powerful voice who captured the spirit of his time.

Selected Works

- Die demolierte Literatur [Demolished Literature] (1897)

- Eine Krone für Zion [A Crown for Zion] (1898)

- Sittlichkeit und Kriminalität [Morality and Criminal Justice] (1908)

- Sprüche und Widersprüche [Sayings and Contradictions] (1909)

- Die chinesische Mauer [The Wall of China] (1910)

- Pro domo et mundo [For Home and for the World] (1912)

- Nestroy und die Nachwelt [Nestroy and Posterity] (1913)

- Worte in Versen (1916–30)

- Die letzten Tage der Menschheit (The Last Days of Mankind) (1918)

- Weltgericht [The Last Judgment] (1919)

- Nachts [At Night] (1919)

- Untergang der Welt durch schwarze Magie [The End of the World Through Black Magic] (1922)

- Literatur (Literature) (1921)

- Traumstück [Dream Piece] (1922)

- Die letzten Tage der Menschheit: Tragödie in fünf Akten mit Vorspiel und Epilog [The Last Days of Mankind: Tragedy in Five Acts with Preamble and Epilogue] (1922)

- Wolkenkuckucksheim [Cloud Cuckoo Land] (1923)

- Traumtheater [Dream Theatre] (1924)

- Epigramme [Epigrams] (1927)

- Die Unüberwindlichen [The Insurmountables] (1928)

- Literatur und Lüge [Literature and Lies] (1929)

- Shakespeares Sonette (1933)

- Die Sprache [Language] (published after his death, 1937)

- Die dritte Walpurgisnacht [The Third Walpurgis Night] (published after his death, 1952)

Works in English Translation

Some of Karl Kraus's works have been translated into English, including:

- The last days of mankind (1974)

- No Compromise: Selected Writings of Karl Kraus (1977)

- In These Great Times: A Karl Kraus Reader (1984)

- Anti-Freud: Karl Kraus' Criticism of Psychoanalysis and Psychiatry (1990)

- Half Truths and One-and-a-Half Truths: selected aphorisms (1990)

- Dicta and Contradicta (2001)

- The Kraus Project: Essays by Karl Kraus (2013)

- In These Great Times and Other Writings (2014)

- The Last Days of Mankind (2015, 2016)

- Third Walpurgis Night: the Complete Text (2020)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Karl Kraus para niños

In Spanish: Karl Kraus para niños

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |