Albert Luthuli facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Inkosi

Albert Luthuli

|

|

|---|---|

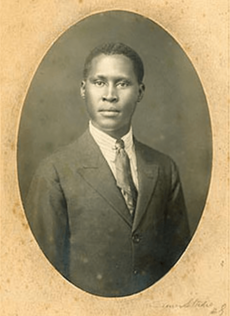

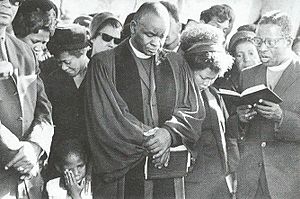

Albert Luthuli c. 1956

|

|

| President-General of the African National Congress | |

| In office December 1952 – 21 July 1967 |

|

| Preceded by | James Moroka |

| Succeeded by | Oliver Tambo |

| Rector of the University of Glasgow | |

| In office 1962–1965 |

|

| Preceded by | Quintin Hogg |

| Succeeded by | John Reith, 1st Baron Reith |

| Chief of the Umvoti River Reserve | |

| In office January 1936 – November 1952 |

|

| Preceded by | Martin Luthuli |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1898 Bulawayo, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) |

| Died | 21 July 1967 Stanger, Natal, South Africa (now KwaDukuza, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa) |

| Resting place | Groutville Congregationalist Church, Stanger, Natal |

| Political party | African National Congress |

| Other political affiliations |

Congress Alliance |

| Spouse |

Nokukhanya Bhengu

(m. 1927) |

| Children | 7 |

| Alma mater | Adams College |

| Occupation | |

| Awards | Nobel Peace Prize United Nations Prize in the Field of Human Rights |

| Religion | Congregationalist |

Albert John Luthuli (born around 1898 – died 21 July 1967) was a South African leader. He fought against apartheid, which was a system of strict racial segregation and discrimination. Luthuli was a tribal chief and a politician.

He served as the President-General of the African National Congress (ANC) from 1952 until his death in 1967. The ANC was a major group fighting for equal rights in South Africa. Luthuli believed in using peaceful methods to achieve change. In 1961, he won the Nobel Peace Prize for his nonviolent efforts against apartheid. He was the first African person to receive this award.

Contents

Albert Luthuli's Early Life

Albert Luthuli was born in 1898 in Bulawayo, which is now part of Zimbabwe. His family was Zulu, and his parents were John and Mtonya Luthuli. He was the youngest of three children. Sadly, his father died when Albert was only about six months old. His mother, Mtonya, raised him. She had grown up in the royal household of King Cetshwayo in Zululand.

Mtonya became a Christian and learned to read the Bible. Albert's father had worked as an interpreter and evangelist at a mission near Bulawayo. After his father's death, Albert and his mother moved back to South Africa.

Growing Up in Groutville

Around 1908, Albert and his mother returned to South Africa. They settled in Groutville, a small Christian community. Albert lived with his uncle, Chief Martin Luthuli. Martin was the first elected chief of Groutville. He was also involved in early African political groups.

Living with his uncle, Albert learned about traditional African politics. He also attended school for the first time. In his Zulu and Christian home, Albert learned duties like fetching water and herding animals.

Albert Luthuli's Education

Albert's mother worked hard to send him to boarding school. In 1914, he went to the Ohlange Institute. This school was founded by John Dube, who was also the first president of the South African Native National Congress (later the ANC). Luthuli later joined the ANC partly out of respect for Dube.

Life at Ohlange was tough during World War I due to food shortages. Albert then moved to Edendale, another school. There, he took part in his first act of civil disobedience. He joined a student strike against a harsh punishment. Even though the protest failed, Albert found his passion for teaching. He graduated with a teaching degree in 1917.

Becoming a Teacher

At 19, Albert became a principal at a small school in Blaauwbosch, Natal. He was the only teacher there. He proved to be a good teacher. In 1920, he received a scholarship to study for a higher teaching diploma at Adams College.

After finishing his studies, he was offered another scholarship to study at the University of Fort Hare. But he chose to work to support his mother. He accepted a teaching job at Adams College. He was one of the first African teachers there. At Adams College, he taught Zulu history, music, and literature. He also met his future wife, Nokukhanya Bhengu, who was also a teacher.

Early Political Involvement

Teachers' and Cultural Associations

In 1928, Albert Luthuli became secretary of the Natal Native Teachers' Association. He later became its president in 1933. This group aimed to improve working conditions for African teachers. They also wanted to encourage teachers to learn more and enjoy social activities.

The association strongly opposed ideas that Africans should only receive "practical" education. This idea later became the basis for the unfair Bantu Education Act. Luthuli also helped start the Zulu Language and Cultural Society in 1935. This group aimed to preserve Zulu culture. However, Luthuli soon left to become a chief. He became disappointed that these groups couldn't bring much change.

Fighting for Cane Growers

Luthuli also helped sugar cane farmers. In 1936, a new law limited sugar production. This hurt African cane growers. Luthuli revived the Groutville Cane Growers' Association. He became its chairman. This group helped farmers work together to get better deals.

They won a big victory: African growers could now share quotas. This meant if one farmer couldn't produce enough, others could sell their cane. Luthuli then formed a larger association for all African sugarcane producers. While they had some small wins, the unfair system in South Africa made it hard for them to succeed. Luthuli realized that the government's policies often blocked progress.

Chief of Groutville

In 1933, Luthuli was asked to become chief of the Umvoti River Reserve. This was his uncle Martin's old position. It took him two years to decide. The chief's salary was much lower than his teaching salary. But Luthuli chose to become chief, saying money was not his main goal. He was elected chief in 1935 and started his duties in January 1936.

Luthuli believed a chief should listen to their people. He governed in a democratic way. He even included women in his decisions. He was seen as "a man of the people."

However, new laws made life harder for Africans. The Hertzog Bills in 1936 limited land for Africans. They also removed Africans from voter lists in some areas. Luthuli saw the problems in Groutville as a small example of what all Africans faced in South Africa.

Native Representative Council

In 1937, the Native Representative Council (NRC) was formed. This was an advisory group for Africans. Luthuli joined the NRC in 1946. He brought up issues like poor land quality for Africans. He also protested the government's harsh actions against striking African miners.

Luthuli felt the government ignored African complaints. He said the NRC was like a "toy telephone" because no one listened. The NRC members eventually refused to cooperate with the government. It was dissolved in 1952. Luthuli realized that working with the government in these structures was not leading to real change.

Leading the ANC in Natal

In 1951, Albert Luthuli was elected president of the Natal branch of the ANC. Younger members of the ANC wanted new leadership. They saw Luthuli as someone who would push for their goals.

Luthuli soon learned about the planned Defiance Campaign. This was a big act of civil disobedience against unfair laws. He asked for more time for Natal to prepare. Some ANC members thought he was a coward. But Luthuli had only just found out about the campaign. Natal eventually agreed to join when ready.

The Defiance Campaign

The Defiance Campaign officially began on 26 June 1952. Thousands of volunteers from the ANC and other groups took part. They were carefully chosen to follow nonviolent resistance methods. People deliberately broke apartheid laws. For example, they used facilities marked "Europeans Only." They sat on benches and used train carriages reserved for white people.

The campaign was peaceful and disciplined at first. But then violence broke out, which was not planned. The police reacted harshly, and many Africans were shot. The government saw the campaign as a threat. They passed new laws to control people, like the Criminal Law Amendment Act. This allowed people to be banned without trial. The ANC ended the campaign in January 1953.

Despite this, the campaign was a success in other ways. The ANC's membership grew from 25,000 to 100,000. For the first time, different racial groups worked together. This led to the formation of the Congress Alliance in 1954. Because of Luthuli's role in the campaign, the government told him to choose. He had to pick between being a chief or an ANC member. He refused, and the government removed him as chief in November 1952.

President-General of the ANC

In December 1952, Albert Luthuli was elected President-General of the ANC. Nelson Mandela became his deputy. Luthuli led the ANC during very difficult times. Many of his fellow leaders were banned or imprisoned. The government passed laws like the Suppression of Communism Act. This gave police huge power over people who criticized the government.

Banning Orders

On 30 May 1953, the government banned Luthuli for a year. This meant he could not attend political meetings or enter major cities. This was the first of four banning orders he would receive. After his first ban ended, Luthuli continued to speak at anti-apartheid meetings.

In 1954, he was banned again for two years. This time, he was confined to his home area of Groutville. He could not even attend a protest against forced removals in Johannesburg.

The Freedom Charter

In 1955, the Congress of the People was held. This was a big meeting where all South Africans were invited to create a Freedom Charter. Luthuli helped create the Congress Alliance. This group included the ANC and other multiracial organizations. Luthuli believed this alliance would help bring freedom to South Africa.

The Freedom Charter was a list of demands for a democratic, multiracial, and free South Africa. It was inspired by human rights ideas. Luthuli could not attend the Congress of the People due to his ban and health issues. He was honored with the Isitwalandwe, an award for those who fought for freedom.

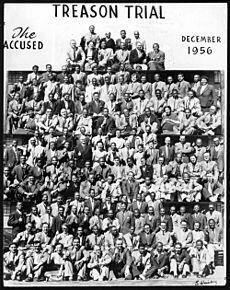

The Treason Trial

In December 1956, Luthuli was arrested during the Treason Trial hearings. He was one of 156 leaders accused of treason for opposing apartheid. Treason was a very serious charge. The government claimed they were part of a "communist conspiracy." Luthuli often dismissed these claims.

The trial covered events like the Defiance Campaign and the Congress of the People. Luthuli was among 65 people whose charges were dropped in December 1957. The trial continued for others, but all remaining defendants were found not guilty in March 1961. Luthuli's involvement in the trial drew international attention. Many people around the world began to sympathize with the anti-apartheid cause. This also led to his name being suggested for the Nobel Peace Prize.

ANC Banned and Shift to Armed Struggle

In May 1959, Luthuli received his third banning order. This ban lasted five years and confined him to his home district. In March 1960, a peaceful protest in Sharpeville ended with police killing 69 people. Luthuli and other ANC leaders burned their passbooks in protest. Passbooks were identity documents that controlled the movement of black South Africans.

After Sharpeville, the government declared a state of emergency. They banned the PAC and the ANC. Luthuli and other leaders were arrested for burning their passbooks. He was fined and given a suspended jail sentence.

After returning home, Luthuli's influence as President-General began to lessen. The ANC was banned, and many leaders were imprisoned or exiled. Some ANC members, like Nelson Mandela, started to believe that nonviolent methods were no longer enough. They felt the movement needed to consider armed resistance.

Formation of uMkhonto we Sizwe

In 1961, Nelson Mandela urged the ANC to adopt armed self-defense. He argued that the bans on the ANC meant they needed new strategies. Luthuli did not support armed struggle at first. He worried that ANC members were not ready for fighting.

However, Luthuli did not completely oppose it. He suggested that the ANC could remain nonviolent. But a separate military group could be formed, linked to the ANC. This group would be called uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK). MK's goal was to damage South Africa's economy without bloodshed. They aimed to force the government to negotiate. Mandela assured Luthuli that MK would only attack military sites, transport links, and power plants. This eased Luthuli's fears about loss of life.

Nobel Peace Prize

In October 1961, Albert Luthuli was awarded the 1960 Nobel Peace Prize. He received it for his nonviolent fight against apartheid. He was the first African person to win this award. This prize made Luthuli famous around the world. Leaders from many countries, including US President John F. Kennedy, sent him congratulations.

Luthuli used his new platform to speak out. He asked the United Nations and other countries to put economic sanctions on the South African government. His words made the world focus on apartheid. In his Nobel Peace Prize speech, he spoke about people of all races working for peace in South Africa. He said that true patriots would not stop until everyone had equal rights and opportunities.

The South African government and many white South Africans reacted negatively. Luthuli had to get special permission to travel to Oslo, Norway, to receive the prize. After he returned, government officials criticized him. They said his speech justified restricting his movement. However, some white South Africans and newspapers did congratulate him. They urged the government to listen to African leaders.

International Recognition

After winning the Nobel Peace Prize, Luthuli became very well-known internationally. In 1962, students at the University of Glasgow in Scotland elected him as their Lord Rector. This was an honorary position. Luthuli was the first African and non-white person to be chosen for this role. He could not attend meetings, but his election showed global support for him.

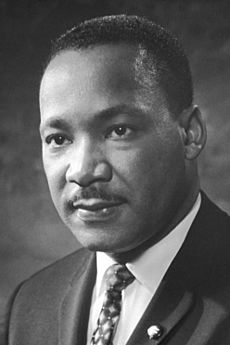

Luthuli's commitment to nonviolence was admired by Martin Luther King Jr.. In 1962, King and Luthuli issued a joint appeal against apartheid. This helped connect the anti-apartheid movement with the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. King encouraged Americans to boycott South Africa. In 1964, when King received his own Nobel Peace Prize, he mentioned Luthuli. He called Luthuli a "pilot" of the freedom movement.

An artist named Ronald Harrison created a painting in 1962 called "The Black Christ." It showed Luthuli as Jesus being crucified. The painting caused a lot of controversy in South Africa. The government banned it and ordered it to be destroyed. But supporters smuggled it to the United Kingdom. It was used to raise money for political prisoners. Harrison was arrested and tortured for his painting. He later met Luthuli in secret.

Final Years

In May 1964, Luthuli received his fourth and most severe banning order. This ban prevented him from traveling even to the closest town, Stanger. He was increasingly isolated from the ANC. But he still managed to send messages to the world through visitors. One important visitor was US Senator Robert F. Kennedy in 1966. Kennedy flew by helicopter to Groutville to meet Luthuli. They discussed the anti-apartheid and civil rights movements. Kennedy later called Luthuli one of the most impressive men he had ever met.

Luthuli's health began to decline in his final years. He had suffered a stroke and heart attack earlier. He spent his last months focused on religion. He was not as active as President-General of the ANC.

Death

On Friday, 21 July 1967, Albert Luthuli left his home to walk to his store. He often walked between his home, store, and sugar cane field. Around 10:40 AM, Luthuli was struck by a goods train while crossing the Umvoti River railway bridge.

The train driver said he blew the whistle when he saw Luthuli. Luthuli was still alive when the driver and fireman reached him. He was taken to Stanger Hospital. Doctors treated his head injuries. His son, Christian, arrived to see him. Luthuli's condition worsened, and he died at 2:25 PM. His wife, Nokukhanya, arrived just minutes after his death.

Reactions to His Death

Many people around the world suspected foul play after Luthuli's death. They thought the South African government might have been involved. The ANC and its allies immediately suspected the government. Some of Luthuli's family members also believe he was murdered.

However, an official investigation concluded he was killed by the train. Historians note that Luthuli's role in the anti-apartheid movement had changed. After the ANC was banned and leaders were imprisoned, Luthuli had less direct contact with the movement. He was still an important symbol, but his active leadership had lessened.

See Also

In Spanish: Albert John Lutuli para niños

In Spanish: Albert John Lutuli para niños

- International Fellowship of Reconciliation

- List of black Nobel laureates

- List of people subject to banning orders under apartheid

Images for kids

-

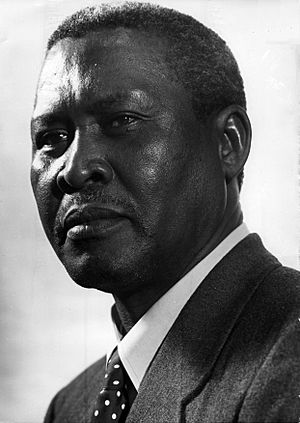

Prime Minister Hertzog passed a set of bills that negatively affected and restricted the African population

-

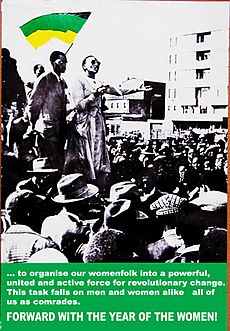

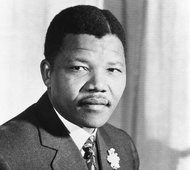

uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK) was formally launched by Nelson Mandela on 16 December 1961.