History of the African National Congress facts for kids

The African National Congress (ANC) is a political party that has been in charge of the Republic of South Africa since 1994. It was started on 8 January 1912 in Bloemfontein. The ANC is the oldest liberation movement in Africa, meaning it was one of the first groups to fight for freedom from unfair rule.

Until 1923, it was called the South African Native National Congress. The ANC began as a place for black South Africans to talk about their problems and push for their rights. Sometimes they used peaceful methods, and other times they used stronger actions. In its early days, the group was small. It included traditional leaders and educated people. They were loyal to the British crown during World War I. In the early 1950s, after the National Party started its policy of apartheid (a system of racial separation), the ANC grew much larger.

In 1952, many people joined the ANC during the Defiance Campaign. This was a time of civil disobedience, where people peacefully broke unfair laws. New leaders like Nelson Mandela, Oliver Tambo, and Walter Sisulu guided the ANC. In 1955, the ANC signed the Freedom Charter. This important document, along with the Treason Trial, brought the ANC closer to other groups fighting against apartheid. This group was called the Congress Alliance.

Around 1960, big changes happened. In 1959, some members left the ANC to form the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). They disagreed with the ANC's idea of including all races in the fight for freedom. Another big change came in March 1960. After the Sharpeville massacre, where police shot peaceful protesters, the government banned the ANC. This forced the ANC to go underground. The ANC and the South African Communist Party (SACP) then created Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK). This became the ANC's military branch. MK started an armed struggle against apartheid, using sabotage to damage government property.

By 1965, many top leaders were in prison after trials like the Rivonia Trial. The ANC had to go into exile, meaning its leaders lived outside South Africa. It stayed in exile until it was unbanned in 1990. For most of this time, Oliver Tambo led the ANC. Its main offices were in Tanzania and then Zambia. Countries like Sweden and the Soviet Union supported the ANC. During these years, the ANC worked to end apartheid using four main ways: armed struggle, an underground network inside South Africa, getting people to protest, and making the world turn against the apartheid government. After the 1976 Soweto uprising, many young people joined MK. ANC attacks sometimes caused civilian deaths, but the ANC also started secret talks to end apartheid peacefully.

The ANC was allowed to operate again on 2 February 1990. Its leaders returned to South Africa to start formal talks. After being released from prison, Nelson Mandela was elected president of the ANC in 1991. In the 1994 elections, which ended apartheid, the ANC became the main party in the government. Mandela was elected national president. The ANC has been in control of the national government ever since.

Contents

How the ANC Started

The ANC began as the South African Native National Congress (SANNC) in Bloemfontein on 8 January 1912. This was soon after the country became the Union of South Africa and before the unfair Natives Land Act was passed. At the first meeting, Zulu hymns were sung.

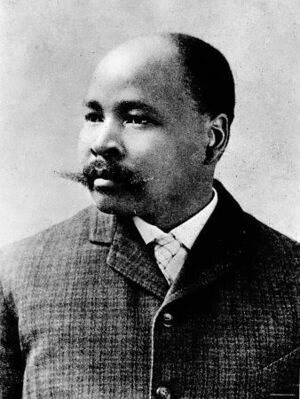

Early members were mostly educated black South Africans and chiefs. Leaders like John Dube (President), Sol Plaatje (Secretary), and Pixley ka Isaka Seme (Treasurer) wanted to help black people. They also wanted to protect their traditions. The group aimed to be a place to discuss issues affecting "the dark races" and to push for changes. They planned to use peaceful methods like protests and asking for support from lawmakers. They also looked at tactics used by Mahatma Gandhi in India, like "passive action."

In its early years, the Congress used moderate methods. For example, in 1914 and 1919, they sent groups to Britain to ask for help from the British government to protect black South Africans' rights. Later, they started to get involved in protests against "pass laws" (laws that forced black people to carry special documents). They also supported striking workers. Pass laws were a main target for the Congress for many years. The Congress protested these laws through peaceful resistance, similar to Gandhi's ideas.

In the 1920s, more people in South Africa became interested in socialist ideas. The Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) was formed in 1921, and some Congress members became socialists. The early Congress was not very centralized. The main group met only once a year. Membership was officially only for black men, but women were allowed to join from 1943.

The ANC, renamed in 1923, was led by Josiah Gumede from 1927. He wanted to get more people to join local branches. This didn't fully happen, but the ANC did support the League of African Rights, a group that fought for civil and political rights. However, in 1929, the ANC decided not to support big anti-pass protests. Gumede was voted out in 1930. His replacement, Seme, focused on traditional chiefs and made the ANC less radical. During this time, the ANC was not very influential.

In the 1940s, the ANC became stronger and more active under President-General Alfred Bitini Xuma. In 1943, the ANC signed the "African Claims" document. This document demanded self-government and political rights for black people, showing a change in the ANC's goals. Xuma worked with the CPSA and Indian Congresses (groups representing Indian South Africans) to fight unfair laws. In 1947, the ANC signed a cooperation agreement, the "Three Doctors' Pact," with the Indian Congresses. By that year, the ANC had many more members, especially because it started holding large public meetings.

Fighting Apartheid

The 1948 election brought the National Party to power. This party supported apartheid, a system that separated people by race. The new Prime Minister, D. F. Malan, started putting apartheid laws into action. These laws limited the rights of non-white South Africans. This made the ANC change its approach. The Suppression of Communism Act of 1950 was especially important. It was used to ban many ANC members and leaders, stopping them from political activity. By 1955, 42 ANC leaders, including Walter Sisulu, were banned.

In the 1950s, the ANC increased its protests inside South Africa. It also started asking other countries to put sanctions (penalties) on the apartheid government. In 1958, ANC President Albert Luthuli called for sanctions. The next year, some ANC members in London started the "Boycott South Africa" movement.

Young Leaders Step Up

While apartheid was being set up, the ANC itself was changing. Younger activists from the ANC Youth League, like Sisulu, Nelson Mandela, and Oliver Tambo, became important. This Youth League, formed in 1944, believed in "Africanist" ideas. They wanted black leaders and for South Africa to be truly independent.

In December 1949, at the ANC's conference, the Youth League successfully pushed for James Moroka to replace President Xuma. Sisulu became Secretary-General, and the Youth League got six seats on the ANC's main committee. The League introduced a "Programme of Action." This plan called for African nationalism and using mass protests like strikes and boycotts. These methods had been used by other groups but not much by the ANC before.

From 1950, the ANC started to use mass actions more often. In 1950, the ANC supported a May Day "stay-away" (a general strike), which led to 18 deaths when police clashed with protesters. Later, on 26 June 1950, the ANC and Indian Congress organized a "Day of Protest" against the shootings and the anti-communism law.

The Defiance Campaign

In 1951, the ANC, the Indian Congress, and the coloured Franchise Action Council planned a joint campaign of mass civil disobedience. This was inspired by earlier peaceful protests. The Defiance Campaign started on 26 June 1952. It targeted six unfair laws, including the Group Areas Act and the Suppression of Communism Act. The ANC had demanded these laws be removed.

Even though the protests were peaceful, the idea of "defiance" was a stronger message than their earlier "passive" resistance. Thousands of volunteers were trained to break laws peacefully. About 8,000 people were arrested. The campaign ended in 1953 when new harsh laws were passed. The Public Safety Act allowed the government to declare a state of emergency. The Criminal Law Amendment Act punished civil disobedience with prison or whipping.

In July 1952, 20 or 21 non-white leaders of the campaign, including Mandela, Sisulu, and ANC President Moroka, were charged under the Suppression of Communism Act. They were found guilty but given suspended sentences. However, Moroka had lost favor with the ANC because he tried to defend himself separately and spoke against the Defiance Campaign. In December 1952, Albert Luthuli, who became well-known during the campaign, was elected ANC President.

The ANC's membership grew from about 7,000 to 100,000 during the Defiance Campaign. In 1953, Mandela suggested a new system called the "M Plan." This plan divided branches into small "cells" based on streets, each led by a steward. This helped the ANC organize better. Since civil disobedience became too risky, the ANC turned to boycotts, demonstrations, and non-cooperation. The ANC also started working more closely with other anti-apartheid groups. For example, in 1952, the ANC and Indian Congress called for a new anti-apartheid group open to white people. This led to the creation of the South African Congress of Democrats in 1953.

The Freedom Charter

At an ANC meeting in August 1953, Z. K. Matthews suggested a national meeting for all South African groups to create a "Freedom Charter." The ANC agreed, and the Congress of the People was held in Kliptown, Soweto, in June 1955. Other groups also cooperated. The groups at this meeting formed the Congress Alliance.

The meeting approved the Freedom Charter. This document was based on demands from many people and became a key text for the anti-apartheid struggle. It spoke about general freedoms found in human rights documents, but also directly addressed the unfairness of apartheid. The charter and the meeting itself were open to all races, even though the individual groups were separated by race.

A famous part of the charter says: "We, the People of South Africa, declare for all our country and the world to know: that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white, and that no government can justly claim authority unless it is based on the will of all the people... And we pledge ourselves to strive together, sparing neither strength and courage, until the democratic changes here set out have been won... Let all who love their people and their country now say, as we say here: 'THESE FREEDOMS WE WILL FIGHT FOR, SIDE BY SIDE, THROUGHOUT OUR LIVES, UNTIL WE HAVE WON OUR LIBERTY.'"

The charter also called for the government to take control of South Africa's mineral wealth and other parts of the economy. By 1955, the ANC's leaders and members were more likely to come from legal or trade union backgrounds, different from the earlier religious leaders.

The Treason Trial

In December 1956, 156 important figures from the Congress Alliance were arrested and accused of treason. The Freedom Charter was used as evidence against them. Among those charged were Mandela, Sisulu, Tambo, and ANC President Luthuli. All of them were released or found not guilty by 1961. The long trial made it hard for ANC leaders to do their organizational work. However, the trial also strengthened the bonds between the Congress Alliance members. Mandela joked that being held together in prison cells was "the largest and longest unbanned meeting of the Congress Alliance in years."

A New Party Forms

In April 1959, some young Africanists left the ANC to form the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). They were led by Robert Sobukwe. These Africanists disagreed with the Freedom Charter and the Congress Alliance. They felt the ANC was moving away from African nationalism by including whites and communists.

Sobukwe explained that "multi-racialism" meant keeping different racial groups separate, which he saw as a form of "racialism multiplied." He said: "We aim, politically, at a government of the Africans by the Africans for Africans, with everybody who owes his only loyalty to Afrika and who is prepared to accept the democratic rule of an African majority being regarded as an African."

The Africanists also believed that a nationalist message would attract more people than the Congress Alliance. Sobukwe thought a liberation movement should "show the light" to the people, who would then act on their own. The ANC leaders, however, felt they should guide the people more directly. The ANC and PAC quickly became rivals.

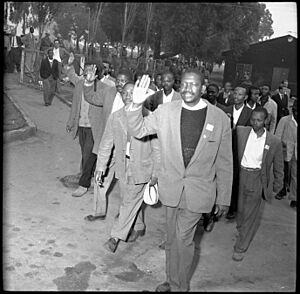

The ANC is Banned

On 21 March 1960, police opened fire on an anti-pass protest organized by the PAC in Sharpeville. Sixty-nine people were killed and 180 injured. The PAC had planned its protest to happen before the ANC's own anti-pass campaign. In response, the ANC declared a day of mourning, and leaders publicly burned their passes. The government declared a state of emergency. On 8 April, both the ANC and the PAC were banned. They remained banned for almost 30 years, until February 1990.

Fighting from Underground

Starting an Armed Struggle

After the Sharpeville massacre, the ANC decided to stop using only non-violent resistance. In December 1960, the South African Communist Party (SACP), which included ANC leaders like Mandela and Sisulu, agreed that the Congress movement should rethink its non-violence policy. In June 1961, Mandela suggested a "turn to violence" to the ANC leadership.

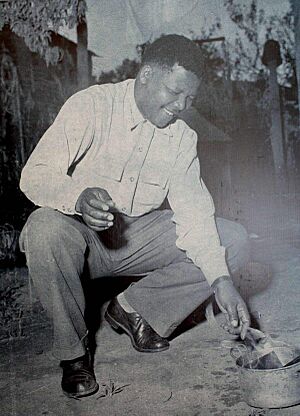

Later that year, a military group called Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), meaning Spear of the Nation, was formed. Mandela was its first commander. Other leaders included Sisulu and Joe Slovo from the SACP. At first, MK was not an official ANC group. It was seen as a separate organization created by members of both the SACP and the ANC. This meant MK could have members of all races, even though the ANC itself was only open to black Africans at that time. The ANC officially recognized MK as its armed wing in October 1962.

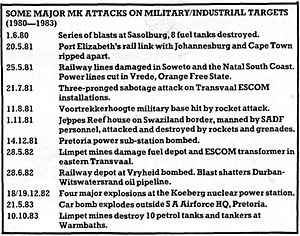

MK started a campaign of sabotage attacks. On 16 December 1961, they bombed empty government buildings. In May 1962, a document by Mandela, Tambo, and Robert Resha called these attacks "the first phase of a comprehensive plan for the waging of guerrilla operations." The ANC agreed to this plan in October 1962. However, sabotage attacks remained MK's main activity, with about 200 attacks between 1961 and 1964.

Leading from Afar

After being banned in April 1960, the ANC had to go underground. Many of its leaders were banned or arrested, including Mandela in 1962. In 1963, many top MK leaders were arrested during a raid on Liliesleaf farm. Mandela, Sisulu, Ahmed Kathrada, Govan Mbeki, and others were sentenced to life in prison after the Rivonia Trial.

From about 1963, the ANC mostly operated from outside South Africa. Its main offices were first in Morogoro, Tanzania, and later in Lusaka, Zambia. Oliver Tambo, who had been sent to set up the external mission in March 1960, became the ANC's leader. When Luthuli died in 1967, Tambo became the acting ANC President. MK training started in Dar es Salaam in 1963. By 1965, MK activities were focused at its Kongwa camp in Tanzania. During this time, the ANC's presence inside South Africa was very weak.

Changes in Exile

In its early years in exile, MK focused on training new members. However, many MK members felt frustrated because they weren't carrying out enough operations inside South Africa. In 1967 and 1968, MK launched campaigns to send fighters back into South Africa. These campaigns largely failed, and many MK fighters were killed or imprisoned.

After these failures, Chris Hani and other fighters wrote a document criticizing the ANC leadership. They mentioned corruption and focusing too much on international support instead of fighting at home. The seven people who signed this document were suspended.

In response to these issues, Tambo called the important Morogoro Conference. This was the ANC's first meeting in exile, held from 25 April to 1 May 1969. Tambo offered to resign as acting ANC President, but the conference voted to keep him. The conference also brought Hani and the other suspended fighters back. It adopted a new "Strategy and Tactics" document. This document said that taking state power by force was a main goal. It also made it clear that political leadership was more important than military action.

The conference decided to allow non-black people to join the ANC. Although the main committee (NEC) was still only for black members, a powerful multi-racial Revolutionary Council was created. This council, led by Tambo, oversaw both political and military efforts against apartheid inside South Africa.

More Armed Actions

From the mid-1970s, it became easier to carry out armed struggle. Angola and Mozambique became independent in 1975, allowing the ANC to set up bases closer to South Africa. Also, after the Soweto uprising in 1976, thousands of students left South Africa to get military training. The ANC in exile grew from 1,000 members in 1975 to 9,000 in 1980, mostly new MK fighters.

In March 1979, the ANC leadership, now in Lusaka, reviewed its strategy. They published the "Green Book," which outlined the "Four Pillars of the Revolution": armed struggle, an underground network, getting people to protest, and isolating the apartheid government internationally. The new military plan focused on urban areas, not just rural guerrilla warfare. In 1979, Tambo also asked Slovo to create a special operations unit. This unit focused on "armed propaganda," meaning attacks on important government targets to attract new MK recruits. For example, on 1 June 1980, the unit bombed the Sasol oil refinery, causing huge damage.

MK guerrilla activity increased steadily. By 1986, attacks on police, community leaders, and government buildings were common. The ANC said that any civilian deaths were accidental. However, a number of civilians were killed in attacks like the 1983 Church Street bombing. Publicly, Tambo said the ANC's main goal was not military victory, but to force the government to negotiate.

During this time, the South African Defence Force (the apartheid military) attacked ANC bases in neighboring countries. Several ANC members were also targeted for assassination.

Challenges in Exile

The ANC's security department, known as NAT, grew a lot after 1976. It screened new recruits to make sure they weren't government agents. The security part of NAT was called Mbokodo. By 1980, Tambo was worried that it was stopping people from disagreeing and making members unhappy. There were later many claims that Mbokodo had detained and even executed some MK members without trial.

In 1980 and 1981, problems between MK and the Zambian government arose. This was mainly because a large hidden weapons cache was found on an ANC farm. This caused panic among ANC leaders about poor discipline among MK members.

In December 1983, a mutiny (rebellion) happened at the MK camp in Viana, Angola. This event was called Mkatashinga, meaning exhausted soldier. The fighters demanded to be sent to fight in South Africa, not in the Angolan Civil War. They also complained about Mbokodo. Several MK members died in fights between the rebels and loyalists. Others were arrested and put in prison camps. This was called "the most shameful episode in the history of the ANC."

After the mutinies, the ANC set up a commission to investigate the complaints. Its 1984 report, known as the Stuart report, found no evidence that enemy agents caused the problems. It made recommendations to improve conditions in the camps.

Important Meetings Abroad

Because of the mutinies, the ANC held its second big meeting in Kabwe, Zambia, in mid-1985. One of the mutineers' demands was for such a conference. A report to the conference admitted that some NAT staff had made "terrible mistakes." The conference agreed to fix NAT, adopt a code of conduct, and set up internal legal procedures.

At Kabwe, the main committee (NEC) was fully elected for the first time in decades. Tambo was permanently elected ANC president, a role he had held for 18 years. All racial barriers to NEC membership were removed, and Slovo became the first white person elected. The conference also decided to hold such meetings with elections every five years.

These changes followed a reorganization in 1983. The Revolutionary Council was replaced by the Politico-Military Council, which had various regional committees and a formal military command structure for MK.

Friends Around the World

For much of its time in exile, the ANC was not supported by the United States and United Kingdom. In 1986, U.S. President Ronald Reagan called some ANC actions "calculated terror." In 1987, U.K. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher also called the ANC a terrorist organization. The ANC and Mandela were not removed from the U.S. terror watch list until 2008.

However, the ANC had a close relationship with the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union was strongly against the apartheid government. Much of the Soviet support came through the ANC's close ties with the SACP. From the 1960s, the ANC had "direct access" to Soviet leaders. In 1961, SACP leaders visited Moscow to explain their plans for armed struggle and got support. Tambo himself visited Moscow in 1963, and ANC groups regularly went to Moscow.

The ANC received a lot of Soviet support. From 1962, ANC members who could become leaders were sent to the Soviet Union for training. Thousands of MK recruits also received military training there. Between 1963 and 1990, the Soviet Union gave the ANC about 61 million roubles in aid. This included military supplies like tens of thousands of guns, other supplies, and technical help and training. This support continued until 1990.

Secret Talks Begin

From the mid-1980s, pressure from other countries and inside South Africa made the apartheid government's position look weak. Some ANC leaders started thinking about negotiating with the South African government to end apartheid. From September 1985, the ANC hosted meetings in Zambia and Zimbabwe with groups from South Africa. These groups included business leaders and trade unions. ANC representatives, especially Thabo Mbeki, also secretly met with businessmen and government officials.

However, the armed struggle continued. There was some disagreement within the ANC about whether to pursue a peaceful settlement. It was a risky strategy if it made their supporters unhappy or if it meant giving up armed struggle for nothing.

In this situation, Tambo approved a secret plan called Operation Vula in 1986. Through this, the ANC aimed to rebuild its armed underground and political leadership inside South Africa. ANC leaders like Mac Maharaj and Ronnie Kasrils secretly returned to South Africa. They also set up a secret way for Tambo and Mandela to communicate. Mandela, still in prison, was also talking with the government on the ANC's behalf. When the police found out about Vula in 1990, eight ANC leaders were charged with terrorism. This caused a big problem at the start of the formal negotiations to end apartheid.

Back Home and in Power

On 2 February 1990, State President F. W. De Klerk unbanned the ANC and other illegal groups. He announced the start of formal negotiations for a peaceful settlement. Mandela was released from prison soon after. These decisions by the apartheid government were due to several reasons. These included the end of the Cold War, a growing economic crisis in South Africa, increasing international pressure, and strong protests inside the country.

Now unbanned, the ANC's leaders could return to South Africa. They set up public offices and took part in the negotiations. The ANC's new headquarters were at Shell House in Johannesburg. In 1997, they moved to their current headquarters at Luthuli House.

The ANC Returns

The Tripartite Alliance was formed in mid-1990. It included the ANC (as the main leader), the SACP, and the powerful Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU). COSATU had already supported the ANC. In 1987, it and many of its groups had adopted the Freedom Charter. Members and leaders of all three groups often belonged to more than one of them.

In December 1990, the ANC held its first national meeting inside South Africa in Johannesburg. This was followed by a big rally in Soweto with speeches by Mandela and Tambo. This was the first official meeting between ANC members who had been in exile, underground, and in prison. The meeting confirmed the leadership elected at the 1985 Kabwe conference. Tambo returned to South Africa the day before the conference, after more than 30 years in exile. The conference thanked Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda and the people of Zambia for hosting the ANC. The conference also decided to consider stopping negotiations if the government did not release all political prisoners, allow all exiles to return, and remove all unfair laws by 30 April 1991.

New Leaders Emerge

In July 1991, at its 48th National Conference in Durban, the ANC elected new leaders. Tambo stepped down after 24 years as president due to a stroke. Mandela was elected to replace him, and Sisulu became his deputy. Importantly, the influential trade union leader Cyril Ramaphosa was elected secretary-general. This showed how the different parts of the ANC (exiles, underground members, and former prisoners) were coming together. It also showed how the ANC was joining with other anti-apartheid groups that had been active inside South Africa. Leaders of the United Democratic Front (UDF), like Trevor Manuel and Cheryl Carolus, were also elected to the main committee. When the UDF officially closed down the next month, even more of its leaders and members joined the ANC.

Towards a New South Africa

The ANC then entered into formal negotiations with the apartheid government to create a new, democratic South Africa.

Government of South Africa

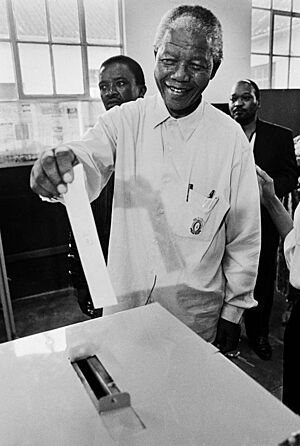

First Democratic Election

South Africa's first democratic elections were held from 26 to 29 April 1994. As expected, the ANC and its partners won easily. They got 62.65% of the national vote and 252 out of 400 seats in the new National Assembly. The ANC also won control of seven out of nine provinces. The National Party won the Western Cape, and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) won KwaZulu-Natal. The ANC decided to accept the IFP's victory to avoid more violence.

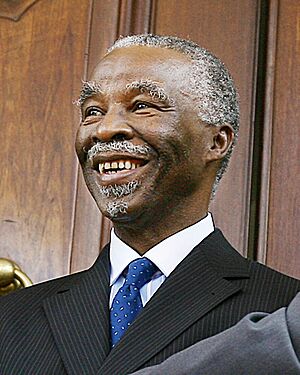

According to the temporary Constitution, the ANC formed a coalition government called the Government of National Unity. This was meant to be a way for different parties to share power during the transition. Mandela became South Africa's first black president and first democratically elected president. Mbeki was his deputy.

Building a New Nation

In December 1994, the ANC held its 49th National Conference in Bloemfontein. The theme was "From Resistance to Reconstruction and Nation-Building." Mandela was re-elected president without opposition, and Ramaphosa was re-elected secretary-general. The rest of the top leadership changed, bringing in younger members. Thabo Mbeki became deputy president, and Jacob Zuma won the national chairmanship. The conference approved a major reorganization of the ANC for the post-apartheid era. It also confirmed key policies like the 1994 Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP), which aimed to improve living conditions for all South Africans.

Facing the Past

In the early 1990s, there were reports of abuses in MK camps while the ANC was in exile. The ANC set up two commissions to investigate these claims. Both found evidence of abuses, especially by the security department (NAT). In 1993, the ANC called for a commission to investigate all human rights abuses during apartheid. The ANC-led government created the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in 1995.

The ANC gave a detailed report to the TRC. It talked about the "just and irregular war for national liberation" it had fought. The ANC admitted to some abuses but stressed that it did not intentionally harm civilians.

The TRC's report, published in 1998, said the ANC was a major victim of human rights abuses during apartheid. However, it also said the ANC had committed abuses. It also said the ANC was partly responsible for the political violence in the early 1990s, especially by arming self-defense groups without proper control.

When the ANC saw the TRC's findings beforehand, it tried to stop the report from being published. Many ANC leaders later rejected the findings. TRC Chairperson Desmond Tutu was surprised by this reaction. The ANC argued that the TRC's findings tried to make the ANC's struggle seem wrong. They said it was wrong to compare the actions of the ANC with the actions of the apartheid state.

New Leadership and Challenges

In the 1999 general election, Thabo Mbeki was elected national president, with Zuma as his deputy. Mbeki had become ANC president in December 1997. Mandela had made it clear he would retire in 1999 and wanted Mbeki to take over. The 1999 elections marked the end of the Government of National Unity. The ANC gained more seats and won control of eight provinces.

In December 1999, the ANC-led government signed large defense contracts, known as the Arms Deal. This deal is often linked to claims of widespread corruption. Some critics say it was a turning point for the ANC government. Arms Deal corruption claims led to many political problems. In 2003, ANC Chief Whip Tony Yengeni pleaded guilty to wrongdoing. The ANC itself was accused of benefiting from the deal.

By 2002, there were rumors of disagreements between the ANC, the SACP, and COSATU. Their main disagreement was about Mbeki's economic policy, which some leftists saw as too focused on free markets. They also felt Mbeki's administration was becoming too centralized.

In the 2004 general election, the ANC gained more seats. It kept its majority in most provinces. After these elections, the National Party, which had done very poorly, announced it would close down. Its members would join the ANC.

Changes in Leadership

Although both Mbeki and Zuma were reappointed after the 2004 election, Mbeki removed Zuma from his post as deputy president on 14 June 2005. This happened after Schabir Shaik was found guilty of corruption related to the Arms Deal, with the court finding that Shaik had made corrupt payments to Zuma. Zuma was replaced by Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka. Even though Zuma soon faced his own accusations of wrongdoing, he remained the ANC deputy president.

An intense rivalry grew between Zuma and Mbeki. Key disagreements included how government jobs were given out and the ANC's relationship with its partners. By April 2007, Mbeki wanted to run for a third term as ANC President. Zuma, with support from the SACP and COSATU, challenged Mbeki. This was the first time the ANC had a contested presidential election since 1952. At the conference in Polokwane, Limpopo, in December 2007, Zuma won the ANC presidency. Many of Mbeki's cabinet members were not re-elected to the main committee.

There was much talk that Mbeki would resign from the national presidency before his term ended. When the accusations against Zuma were brought back, Mbeki was accused of planning a political conspiracy. In September 2008, a judge found evidence of "political meddling" by Mbeki in Zuma's case. Although this judgment was later overturned, the ANC leadership decided that Mbeki should leave his office. Mbeki agreed to resign to avoid a long public fight. About a third of his cabinet also resigned in protest. Mbeki was replaced by Kgalema Motlanthe, who had been elected ANC deputy president. Motlanthe led a temporary government while Zuma campaigned for the 2009 elections.

In response to these events, a group of pro-Mbeki ANC members left and formed a new political party in November 2008, called the Congress of the People (COPE). They were led by former Defence Minister Terror Lekota. In the 2009 elections, COPE won 7.42% of the national vote, becoming the second largest opposition party.

2009–18: Presidency of Jacob Zuma

2009 general election

In the 2009 elections, the ANC won 65.9% of votes nationally. This was still a strong win, but it showed a slight decrease in support for the ANC. At the provincial level, the ANC won control of eight of the nine provinces. However, the ANC clearly lost the Western Cape to the Democratic Alliance (DA). This was because the ANC was becoming less popular among minority voters, especially coloured voters, who make up a large part of the Western Cape's population.

2014 general election

In the 2014 South African general election and later in the 2016 South African municipal elections, the ANC again won a majority of votes, but a noticeably smaller one. In 2016, the DA took control of several important cities, including Johannesburg and Pretoria. The ANC also lost votes to the new Economic Freedom Fighters, which became South Africa's third biggest party.

Nasrec conference

Jacob Zuma was replaced as ANC president by Cyril Ramaphosa at the 2017 ANC national conference.

2018–present: Presidency of Cyril Ramaphosa

2019 general election

The ANC continued to govern after the 2019 South African general election.

Leadership

Presidents

- 1912–1917: John Langalibalele Dube

- 1917–1924: Sefako Mapogo Makgatho

- 1924–1927: Zacharias Richard Mahabane

- 1927–1930: Josiah Tshangana Gumede

- 1930–1936: Pixley ka Isaka Seme

- 1937–1940: Zacharias Richard Mahabane

- 1940–1949: Alfred Bitini Xuma

- 1949–1952: James Sebe Moroka

- 1952–1967: Albert John Luthuli

- 1967–1991: Oliver Reginald Tambo

- 1991–1997: Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela

- 1997–2007: Thabo Mvuyelwa Mbeki

- 2007–2017: Jacob Gedleyihlekisa Zuma

- 2017–present: Matamela Cyril Ramaphosa

Deputy Presidents

- 1912–1936: Walter Rubusana

- 1952–1958: Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela

- 1958–1985: Oliver Reginald Tambo

- 1985–1991: Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela

- 1991–1994: Walter Max Ulyate Sisulu

- 1994–1997: Thabo Mvuyelwa Mbeki

- 1997–2007: Jacob Gedleyihlekisa Zuma

- 2007–2012: Kgalema Petrus Motlanthe

- 2012–2017: Matamela Cyril Ramaphosa

- 2017–2022: David Dabede Mabuza

- 2022–present: Paul Shipokosa Mashatile

Secretary-General

- 1912–1915: Solomon Tshekisho "Sol" Plaatje

- 1915–1917: Saul Msane

- 1917–1919: R.V. Selope Thema

- 1919–1923: H. L. Bud M'belle

- 1923–1927: TD Mweli Skota

- 1927–1930: E. J. Khaile

- 1930–1936: Elijah Mdolomba

- 1936–1949: James Arthur Calata

- 1949–1955: Walter Max Ulyate Sisulu

- 1955–1958: Oliver Reginald Tambo

- 1958–1969: Philemon Pearce Dumasile "Duma" Nokwe

- 1969–1991: Alfred Baphethuxolo Nzo

- 1991–1997: Matamela Cyril Ramaphosa

- 1997–2007: Kgalema Petrus Motlanthe

- 2007–2017: Gwede Mantashe

- 2017–2022: Ace Magashule

- 2022–present: Fikile Mbalula

See also

- History of South Africa

- Anti-Apartheid Movement

- Amandla

- Radio Freedom

- National Conference of the African National Congress

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |