History of South Africa facts for kids

|

|

| Use | Civil and state flag, civil and state ensign |

|---|---|

| Design | The flag of Republic of South Africa was adopted on 26 April 1994. It replaced the flag that had been used since 1928, and was chosen to represent multiculturalism and ethnic diversity in the country's new, post-apartheid democratic society. |

South Africa is a country with a very long and interesting history. Scientists believe that the first modern humans lived here over 100,000 years ago. This makes South Africa a very important place for understanding human history. The land is so important that a region called the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage site was named by UNESCO in 1999.

The earliest people known to live in South Africa were the Khoisan, which includes the Khoekhoe and the San. Around 1,000 BCE, other groups arrived. These were people who migrated from Western and Central Africa in a big movement called the Bantu expansion.

Later, Europeans started exploring the African coast. Portuguese explorers were looking for a new way to reach China. In 1488, they sailed around the Cape of Good Hope. In 1652, the Dutch East India Company set up a trading post in Cape Town. European settlers, known as the Free Burghers, started farms in the Dutch Cape Colony.

In 1795 and 1806, the British took control of the Cape Colony. This led to a big migration of Dutch settlers, called the Great Trek. They created new settlements inland. The discovery of diamonds and gold in the 1800s changed South Africa a lot. It brought new industries and led to conflicts between the Dutch settlers (Boers) and the British.

After the South African War (1899–1902), the Union of South Africa was formed in 1910. It became a self-governing part of the British Empire. In 1961, South Africa became a republic.

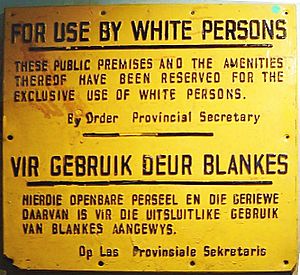

From 1948 to 1994, South Africa had a system called apartheid. This was a strict system of racial segregation and white minority rule. It meant people were separated and treated differently based on their race. After many years of struggle, the first democratic election was held on 27 April 1994. The African National Congress (ANC) won, and Nelson Mandela became the first black president.

Contents

- Early History: Before 1652

- Dutch Colonization: 1652–1815

- British Colonization and Boer Republics: 1815–1910

- Union of South Africa: 1910–1948

- Apartheid Era: 1948–1994

- Post-Apartheid Period: 1994–Present

- See also

Early History: Before 1652

Scientists have found that the area now called South Africa was a key place for human evolution. Early human-like creatures, called Australopithecines, lived here at least 2.5 million years ago. Modern humans settled here around 125,000 years ago.

Ancient Human Discoveries

- Further information: People of Africa

In 1924, Professor Raymond Dart found the skull of a 2.51 million-year-old child, known as the Taung Child. This was the first discovery of Australopithecus africanus. Later, Robert Broom found more early human fossils at Kromdraai and Sterkfontein.

At the Blombos Cave in 2002, stones with engraved patterns were found. They are about 70,000 years old. These might be the earliest examples of abstract art made by humans. More recently, scientists found Australopithecus sediba (1.9 million years old) in 2008. In 2015, a new human species, Homo naledi, was discovered near Johannesburg. These finds are very important for understanding our past.

San and Khoikhoi People

The first people in southern Africa were the San and Khoikhoi tribes. They are often called the Khoisan. The San were hunter-gatherers, meaning they hunted animals and gathered plants for food. The Khoikhoi were pastoral herders, raising livestock like cattle and sheep.

Archaeological finds show that the Khoikhoi settled on the Cape Peninsula about 2,000 years ago. When Portuguese, English, and Dutch sailors arrived in the 15th and 16th centuries, they traded metals for cattle and sheep with the Khoikhoi.

In 1652, the Dutch East India Company set up a trading post at the Cape. This led to conflicts with the Khoikhoi over land. The Khoikhoi were eventually forced out of the area after several wars. Many Khoikhoi also died from a smallpox epidemic brought by Dutch sailors.

The Bantu People's Arrival

The Bantu expansion was a huge movement of people across Africa. Bantu-speaking communities reached southern Africa from the Congo basin as early as the 4th century BC. They moved into Khoikhoi lands, pushing the original inhabitants into drier areas.

Some Bantu groups, like the Nguni peoples (Zulu, Xhosa, Swazi, and Ndebele), settled near the eastern coast. Others, like the Sotho–Tswana peoples (Tswana, Pedi, and Sotho), settled inland on the Highveld plateau. The Venda, Lemba, and Tsonga peoples made their homes in the north-east.

The Kingdom of Mapungubwe was the first African kingdom in southern Africa. It existed between AD 900 and 1300 near the Limpopo and Shashe rivers. It became a wealthy kingdom by controlling trade with places like Arabia, India, and China. They traded gold and ivory for goods like Chinese porcelain. The kingdom was abandoned in the 14th century due to climate changes.

European Colonization Begins

Portuguese Explorers

The Portuguese sailor Bartolomeu Dias was the first European to explore South Africa's coastline in 1488. He was trying to find a sea route to the Far East. He named the southernmost tip of Africa the Cabo das Tormentas, or Cape of Storms.

In 1497, Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope. By December 16, his fleet passed the Great Fish River. Da Gama named the coast he was passing Natal, which means Christmas in Portuguese. His journey opened the Cape Route between Europe and Asia.

Dutch Influence

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) was a powerful trading company. They decided to set up a permanent settlement at the Cape in 1652. Their goal was to create a supply station for their ships sailing the spice route to the East.

Dutch Colonization: 1652–1815

A small VOC expedition, led by Jan van Riebeeck, arrived at Table Bay on April 6, 1652. They needed farmers to grow food for the ships and the growing settlement. These farmers were called "free burghers." They were former VOC soldiers and gardeners who couldn't return to Holland.

The VOC also brought about 71,000 slaves to Cape Town from places like India, Indonesia, and Madagascar.

Most of the burghers were Dutch and belonged to the Dutch Reformed Church. In 1688, French Huguenots, who were Calvinist Protestants escaping religious persecution, joined them.

The VOC imported many slaves because they didn't want to enslave the local Khoi and San people. Over time, the Khoikhoi and San were also forced into labor. The mixed-race descendants of Dutch settlers, Khoi-San, and Malay slaves became known as the Cape Coloureds and Cape Malays. Some mixed-race people were also absorbed into the white population. For example, Simon van der Stel, the first Governor of the Dutch settlement, was of mixed race. He helped develop the South African wine industry.

British Colonization and Boer Republics: 1815–1910

British Take Control of the Cape

In 1795, the British took control of the Cape to prevent it from falling into French hands during the French Revolution. They gave it back to the Dutch in 1803 but seized it again in 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars. British control was officially recognized in 1815.

The British initially saw the Cape Colony as just a useful port. They tried to make the European settlers adopt British language and culture. This made many Dutch colonists, known as Boers, move away from British rule. In 1820, about 5,000 British immigrants settled in places like Grahamstown and Port Elizabeth.

Throughout the 19th century, Britain wanted to protect its trade route to India. This goal was made difficult by conflicts with the Boers, who disliked British authority.

Exploring the Interior

Colonel Robert Jacob Gordon was the first European to explore parts of the interior from 1777 to 1786. His journeys are recorded in his drawings and journals.

Early interactions between European settlers and the Xhosa, the first Bantu people they met, were peaceful. However, competition for land led to conflicts, starting with cattle raids in 1779. These became known as the Xhosa Wars.

British explorers David Livingstone and William Oswell were likely the first white men to cross the Kalahari Desert in 1849. Livingstone received a gold medal for discovering Lake Ngami.

Zulu Kingdom's Rise and Impact

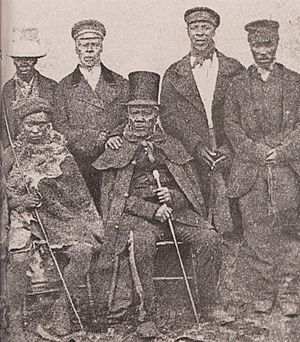

The Zulu people were originally a small clan. In the 1820s, the Zulu Kingdom grew very powerful under Shaka. This period was known as the difaqane (forced migration) or mfecane (crushing).

Shaka kaSenzangakhona built large, disciplined armies. He expanded his kingdom, killing or enslaving those who resisted. His impis (warrior regiments) were very strict. This led to many tribes moving and widespread warfare across southern Africa. It also led to the formation of new nations like Lesotho and Eswatini (formerly Swaziland).

In 1828, Shaka was killed by his half-brothers. Dingaan became king, but he was weaker. The Mfecane caused an estimated 1 to 2 million deaths.

Boer People and Their Republics

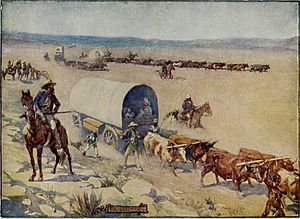

After 1806, many Dutch-speaking settlers, called Boers, moved inland from the Cape Colony. This movement, known as the Great Trek, happened in the 1830s. One reason they left was the British rule that made English the official language. The Boers' culture, religion, and schools were all in Dutch, so this caused problems.

Another reason was the British government's abolition of slavery in 1838. The farmers had invested a lot in slaves and felt they couldn't replace the labor without losing money. The compensation offered by Britain was also difficult to claim.

South African Republic

The South African Republic (ZAR), also called The Transvaal, was an independent Boer nation from 1852 to 1902. Britain recognized its independence in 1852. Under President Paul Kruger, the republic defeated British forces in the First Boer War. It remained independent until 1902, when it surrendered to the British after the Second Boer War. The territory then became the Transvaal Colony.

Orange Free State Republic

The Orange Free State was another independent Boer republic. It started from the British Orange River Sovereignty (1848-1854). Britain withdrew its troops in 1854, and the Boers claimed the area as the Orange Free State.

They fought several wars with the Basotho kingdom over land. In 1900, Britain occupied the Orange Free State during the Second Boer War and renamed it the Orange River Colony. In 1910, it became the Orange Free State Province within the Union of South Africa.

Natalia Republic

Natalia was a short-lived Boer republic founded in 1839 by Voortrekkers from the Cape Colony. In 1824, British settlers had established Durban. The Boers created the Republic of Natalia with its capital at Pietermaritzburg.

In 1842, British forces attacked the Boer camp at Congella. The attack failed, and the Boers besieged Durban. A local trader, Dick King, rode 600 km in 14 days to get British reinforcements. The British arrived, broke the siege, and the Boers retreated. The Boers accepted British rule in 1844. Many who refused to acknowledge British rule moved to the Orange Free State and Transvaal.

Cape Colony's Growth

Between 1847 and 1854, Harry Smith, the governor of the Cape Colony, expanded its territory northwards. This led to conflict with Boers and the Xhosa.

From the mid-1800s, the Cape Colony gained more independence from Britain. In 1854, it got its first elected legislature, the Cape Parliament. In 1872, it became self-governing with its own Prime Minister.

The Cape Colony was unique because its laws did not discriminate based on race. Elections were held under the non-racial Cape Qualified Franchise system, where voting rights applied to everyone, regardless of race.

The discovery of diamonds and gold later brought instability. Cecil Rhodes, a powerful colonialist, became Cape Prime Minister. He limited the multi-racial voting rights and his expansionist policies led to the Second Boer War.

Natal and Indian Immigration

Indian slaves had been brought to the Cape by the Dutch in 1654. After Britain annexed Natalia and renamed it Natal, most Boers left. British immigrants replaced them.

By 1860, slavery was abolished. British colonists in Natal needed workers for their plantations. They turned to India, and the ship Truro arrived in Durban with over 300 Indians. Over the next 50 years, 150,000 more Indian workers arrived. Many free "passenger Indians" also came, forming a large Indian community.

By 1893, when Mahatma Gandhi arrived in Durban, Indians outnumbered whites in Natal. Gandhi's fight for civil rights for Indians was unsuccessful at the time. Until 1994, Indians faced many discriminatory laws.

The Griqua People

By the late 1700s, the Cape Colony had many mixed-race people, called "coloureds". They were descendants of Dutch settlers, Khoikhoi, and imported slaves. Many of these people formed the Griqua people.

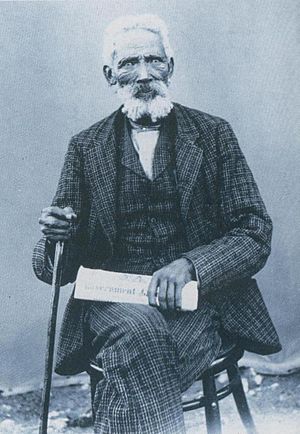

Under Adam Kok, these "coloureds" or Basters (meaning mixed race) moved northwards. They were joined by San, Khoikhoi, and some white outlaws. Around 1800, they crossed the Orange River and settled in an uninhabited area they named Griqualand.

In 1825, some Griquas moved to Philippolis to protect a mission station. This led to conflicts with white settlers over land rights. British troops were sent to the region in 1845.

In 1861, most Philippolis Griquas moved east again, over the Drakensberg mountains. They settled in "Nomansland," which they renamed Griqualand East. Britain annexed it in 1874.

The original Griqualand, north of the Orange River, was renamed Griqualand West in 1871. This happened after the discovery of rich diamond deposits at Kimberley. Griqua leader Nicolaas Waterboer claimed the diamond fields were on Griqua land. The Boer republics also wanted the land. Britain gained control, but the Griquas did not benefit from the diamond wealth.

Wars Against the Xhosa

In early South Africa, Europeans had different ideas about land ownership than African cultures. This led to misunderstandings and conflicts. As European settlers moved inland, they met resistance from the local Bantu people.

The frontier wars between settlers and the Xhosa became known as the Xhosa Wars. The First Xhosa War broke out in 1779. For nearly 100 years, the Xhosa fought the Boers and later the British. In the Fourth Xhosa War (1811-1812), the British pushed the Xhosa back across the Great Fish River.

In 1818, a conflict between Xhosa leaders Ndlambe and Ngqika led to Ngqika's defeat. Ngqika asked the British for help, and Ndlambe attacked the British town of Grahamstown in 1819.

Wars with the Zulu

In the Natal region, Boer trekkers made an agreement with Zulu King Dingane kaSenzangakhona. However, conflicts over cattle led to the killing of a Boer party led by Piet Retief.

The Boers defended themselves against a Zulu attack at the Ncome River on December 16, 1838. This battle, known as the Battle of Blood River, resulted in about three thousand Zulu warriors dying.

Later, in 1879, the British fought the Anglo-Zulu War. The British wanted to bring the African kingdoms and Boer republics under their control. Henry Bartle Frere, the British High Commissioner, sent an ultimatum to Zulu King Cetshwayo to start a war.

The war had very bloody battles, including a big Zulu victory at the Battle of Isandlwana. Britain eventually defeated the Zulus with the help of some Zulu groups who disliked the centralized Zulu authority. This ended the Zulu nation's independence. The British then set up large sugar plantations in the area.

Wars with the Basotho

From the 1830s, white settlers moved into the fertile Lower Caledon Valley, which was occupied by Basotho herders under King Moshoeshoe I. A treaty in 1845 recognized white settlement, but without clear boundaries, this led to clashes. Moshoeshoe thought he was loaning land, while settlers believed they owned it.

The British, who controlled the Orange River Sovereignty, drew a boundary called the Warden Line. This led to conflict, and Moshoeshoe's warriors defeated the British in 1851.

In 1854, the British handed the territory to the Boers, who formed the Republic of the Orange Free State. Wars continued between the Basotho and the Orange Free State from 1858 to 1868. Both sides destroyed land. Moshoeshoe eventually signed a peace treaty in 1858, but boundary issues remained. War broke out again in 1865. In 1868, the British parliament declared the Basotho Kingdom a British protectorate, ending the fighting. It was named Basutoland and is now Lesotho.

Wars with the Ndebele

In 1836, Boer Voortrekkers met the Ndebele people in northwestern South Africa. After several battles, the Ndebele chief Mzilikazi was defeated and led his people north to what is now Zimbabwe.

Other Ndebele groups also clashed with the Voortrekkers. In 1854, 28 Boers were killed by Ndebele chiefdoms. The Ndebele retreated into mountain caves, where they were besieged by Boer commandos. Between 1,000 and 3,000 Ndebele people died in the caves.

Wars with the Bapedi

The Sekhukhune wars were three campaigns fought between 1876 and 1879 against the Bapedi under King Sekhukhune I. These wars happened in the Sekhukhuneland region. Sekhukhune refused to allow gold prospectors on his land.

The first war was fought by the Boers in 1876. The British fought two campaigns in 1878/1879. Sekhukhune eventually surrendered in 1879 and was imprisoned. Sekhukhuneland became part of the Transvaal Republic, but no gold was found there.

Discovery of Diamonds

Diamonds were first found in South Africa in 1866-1867 near the Orange River. By 1869, diamonds were found in hard rock called kimberlite, near the mining town of Kimberley.

The land where the diamonds were found had unclear boundaries. The South African Republic, the Orange Free State, and the Griqua people all claimed it. An arbitrator decided the land belonged to the Griquas. The Griqua leader, Nicolaas Waterboer, then asked for British protection. Griqualand became a British colony called Griqualand West in 1871. It was later added to the Cape Colony in 1877. The Griquas did not benefit from the diamond wealth.

By the 1870s and 1880s, the Kimberley mines produced 95% of the world's diamonds. This wealth helped fund the search for gold and other resources. It also helped the Cape Colony gain more self-government in 1872.

In 1888, Cecil John Rhodes co-founded De Beers Consolidated Mines at Kimberley. He bought up many individual claims. Cheap African labor was key to the success of diamond mining. Some historians believe the wealth from Kimberley influenced the "Scramble for Africa", where European powers divided almost the entire continent among themselves.

Discovery of Gold

Gold was discovered in February 1886 on the Witwatersrand (meaning White Waters Ridge) in the Transvaal. This led to a huge gold rush. Most gold deposits were deep underground, requiring a lot of money and engineering skills to extract. This led to the development of deep-level mines and the "instant city" of Johannesburg.

Within two years, four mining finance houses were established. Cecil Rhodes and Charles Rudd, who had made fortunes from diamonds, started Gold Fields of South Africa. Gold became the main export for decades.

The working conditions in the mines were dangerous and difficult, making it hard to recruit local black Africans. In 1904, Chinese indentured laborers were imported to work for lower wages. By 1907, 53,000 Chinese laborers worked in the gold mines.

First Anglo–Boer War

South African Republic/Transvaal

Orange Free State

British Cape Colony

Natalia Republic

Britain annexed the Transvaal Boer republic in 1877, trying to unite southern Africa under British rule. This led to a rebellion and the First Boer War in 1880. The Boers won a decisive victory at the Battle of Majuba Hill in 1881.

The republic regained its independence as the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR). Paul Kruger became President in 1883. The British still wanted to unite the colonies and republics.

The Anglo-Boer wars were largely about who would control the rich gold mines. The mines were controlled by European "Randlords" and foreign managers. The Boers called these foreigners uitlander, meaning aliens. The "aliens" wanted voting rights and complained about the government.

In 1895, a group of mercenaries led by Leander Starr Jameson entered the ZAR to start an uprising. This was called the Jameson Raid. It failed, and the mercenaries were captured. President Kruger suspected the Cape Colony government, led by Cecil John Rhodes, was involved. Kruger formed an alliance with the Orange Free State. This did not prevent the Second Boer War.

Second Anglo–Boer War

Tensions between Britain and the Boers grew, leading to the Second Boer War in 1899. Britain demanded voting rights for foreign whites in the Witwatersrand. President Paul Kruger refused and demanded British troops withdraw. When they refused, Kruger declared war.

This war lasted longer than the first. British troops were joined by soldiers from other British colonies. The British had many more soldiers than the Boers. By June 1900, the major Boer towns had surrendered. However, some Boers, called bittereinders (those who would fight to the bitter end), continued fighting using guerrilla tactics for two more years. The British responded with scorched earth tactics, destroying farms and homes.

The British suffragette Emily Hobhouse visited British concentration camps in South Africa. She reported on the terrible conditions, where 26,000 Boer women and children died from disease and neglect.

The war affected all people in South Africa. Black people were recruited by both sides. It is known that 17,182 black people died in Cape concentration camps alone, mostly from diseases.

The war ended on May 31, 1902, with the Treaty of Vereeniging. The Boer republics accepted British rule, and Britain promised to help rebuild the areas.

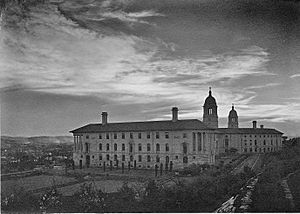

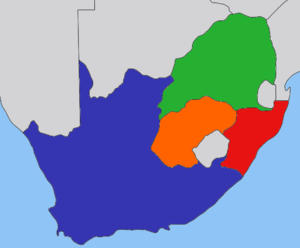

Union of South Africa: 1910–1948

After the Anglo-Boer wars, Britain united the four colonies, including the former Boer republics, into the Union of South Africa. This happened in 1910 with the South Africa Act 1909. The Union became an independent part of the British Empire.

The Union parliament passed harsh segregation laws. The 1913 Natives' Land Act set aside only 8% of South Africa's land for black people. White people, who were 20% of the population, held 90% of the land. This law was a key part of racial discrimination for decades.

General Louis Botha led the first government, with General Jan Smuts as his deputy. Their party was generally pro-British. More radical Boers formed the National Party (NP) in 1914, led by General Barry Hertzog. They focused on Afrikaner interests and independence from Britain.

In 1924, the National Party came to power. Afrikaans, a language developed from Dutch, replaced Dutch as an official language in 1925.

The Union of South Africa ended on October 5, 1960. A majority of white South Africans voted to leave the British Commonwealth and become the Republic of South Africa.

First World War

When World War I started, South Africa joined Britain and the Allies against Germany. Prime Minister Louis Botha and Defence Minister Jan Smuts were former Boer generals who had fought against the British. Now, they became important members of the British war effort.

Some South African soldiers refused to fight Germans and started a rebellion called the Maritz Rebellion in 1914. The government stopped the rebellion.

Public opinion was divided. British South Africans strongly supported the war. Indian South Africans, led by Mahatma Gandhi, also supported it. Afrikaners were split, with some supporting the war and others supporting the rebellion. Many black South Africans supported the war, hoping it would improve their status.

Over 250,000 South Africans of all races volunteered for service. More than 7,000 South Africans were killed. The Battle of Delville Wood and the sinking of the SS Mendi were major losses.

25,000 black South Africans served as non-combatant laborers in France. On February 21, 1917, 616 of them drowned when their ship, the SS Mendi, sank. This was one of South Africa's worst tragedies of the war. Black and mixed-race South Africans were disappointed when white domination and racial segregation continued after the war.

South Africa's help to the British Empire was significant. They occupied two German African colonies. Their ports were important for refueling ships. South Africa also supplied two-thirds of the gold production in the British Empire, which helped fund the war.

Second World War

During World War II, South Africa's ports were vital for the British Royal Navy. South Africa also played a key role in developing radio detection and ranging (radar) technology. By 1945, South African aircraft had intercepted 17 enemy ships and attacked 26 enemy submarines.

About 334,000 South Africans volunteered for military service. Nearly 9,000 were killed. In 1942, almost 10,000 South African soldiers were captured by German forces in Libya. Some South African fighter pilots, like Adolph "Sailor" Malan, served with distinction in the Royal Air Force.

General Jan Smuts was a trusted advisor to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Smuts was appointed a Field Marshal of the British Army in 1941. After the war, he represented South Africa at the drafting of the United Nations Charter in 1945, pushing for a strong international body to keep peace.

Pro-German Views

Some South Africans had pro-German views. After the 1914 rebellion, General Manie Maritz became a German spy. Germany had supplied weapons to the Boers during the Second Boer War.

In the early 1940s, the pro-Nazi Ossewabrandwag (OB) movement grew to half a million members. This group, along with others, was later absorbed into the National Party. The Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB), a white supremacist movement from the 1970s, openly used a flag similar to the swastika. They tried to stop the country's transition to democracy in the 1990s.

Apartheid Era: 1948–1994

The policies of apartheid were based on earlier colonial laws. From 1948, the National Party formalized and expanded this system of racial discrimination. Apartheid lasted until 1991.

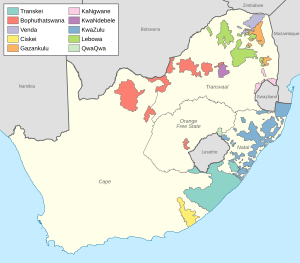

A key law was the Homeland Citizens Act of 1970. This law created "homelands" or "reserves" for black people, also known as "Bantustans". Thousands of African people were forced to move from urban areas to these homelands. This policy also applied to South West Africa (now Namibia).

Apartheid led to violent conflict and a militarized society. By 1987, military spending was about 28% of the national budget. After the 1976 Soweto uprising, the police and military gained a lot of power in government decisions.

UN Actions Against Apartheid

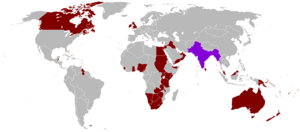

On December 16, 1966, the United Nations General Assembly called apartheid a "crime against humanity." In 1973, the Apartheid Convention declared it unlawful and criminal. The UN General Assembly suspended South Africa from the UN in 1974. In 1977, the UN Security Council imposed an arms embargo, stopping the sale of weapons to South Africa. South Africa responded by strengthening military ties with Israel and building its own arms industry.

Secret Killings

In the mid-1980s, police and army death squads secretly killed people who opposed the government. By 1987, at least 140 political assassinations had happened in the country. The government also spread false information to hide these killings. State-sponsored groups attacked communities that resisted apartheid, and the government blamed these attacks on "black-on-black" violence.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) later found that secret networks of police and army members were involved in human rights violations, including killings. The TRC reported that the Inkatha Freedom Party was responsible for 4,500 deaths, the South African Police for 2,700, and the ANC for about 1,300 between 1960 and 1994.

In 2002, a planned military coup by a white supremacist group called the Boeremag was stopped by the police. This showed that the new democratic government was strong.

Military Actions in Neighboring Countries

During apartheid, South African security forces tried to destabilize neighboring countries. They supported opposition groups, carried out sabotage, and attacked ANC bases. These neighboring countries were known as the Frontline States: Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Mozambique, Swaziland, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

In 1975, after Portugal granted independence to Angola, a civil war broke out. South Africa intervened to support one side, UNITA. In response, Cuba sent 18,000 soldiers to support the MPLA. The Cuban intervention helped the MPLA win. The civil war in Angola caused many deaths, mostly from famine.

Between 1975 and 1988, South Africa continued to raid Angola and Zambia. A controversial attack in 1978 at Cassinga in Angola killed about 700 South West Africans. The UN Security Council condemned this attack. South Africa's involvement in Angola ended in 1988 with an agreement that led to the withdrawal of all foreign troops from Angola and South Africa's withdrawal from Namibia.

South Africa also supported rebels in Mozambique and launched raids into Lesotho, Swaziland, and Botswana.

Resistance to Apartheid

Organized resistance to apartheid came from many groups. The Torch Commando, formed in the 1950s, was a large white protest movement. Some of its members later joined the armed wing of the ANC.

From the 1940s to the 1960s, anti-apartheid resistance was mainly peaceful. However, after the 1960 Sharpeville massacre and the banning of anti-apartheid parties like the African National Congress (ANC), resistance turned to armed struggle. The ANC's armed wing, Umkhonto weSizwe (MK), carried out acts of sabotage and attacks on military and police.

In the early 1960s, some members left the ANC to form the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC) and its military wing, Poqo. Poqo later became the Azanian People's Liberation Army (APLA). They carried out armed robberies and, in the 1990s, attacked white civilian targets.

The 1976 Soweto uprising was sparked by a government law forcing African students to learn in Afrikaans. This uprising spread, and hundreds of protesters were killed or arrested. Many students fled to neighboring countries and joined the ANC or PAC military wings.

The United Democratic Front (UDF) was formed in 1983. It was a non-racial coalition of many organizations. It had millions of members and used strategies like rent boycotts and student protests. The UDF had a strong relationship with the ANC.

Between 1960 and 1990, 130 political prisoners were executed in Pretoria Central Prison.

Post-Apartheid Period: 1994–Present

The dissolution of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s meant the African National Congress (ANC) could no longer rely on the Soviet Union for support. It also meant the apartheid government could no longer claim it was protecting against communism. Both sides were forced to negotiate.

On February 2, 1990, President F. W. de Klerk announced the lifting of the ban on the African National Congress and the release of political prisoner Nelson Mandela after 27 years in prison. In a 1992 referendum, 68% of white voters supported democracy.

After long negotiations, a draft constitution was published in 1993. It included equal voting rights for all races. From April 26-29, 1994, South Africans voted in the first universal suffrage elections. The African National Congress won.

Nelson Mandela was elected President on May 9, 1994. He formed a Government of National Unity with the ANC, the National Party, and Inkatha. On May 10, 1994, Mandela became South Africa's new President. The government later enacted a new Constitution and Bill of Rights in 1996. The death penalty was abolished, and new laws for land reform and labor rights were introduced.

The ANC had promised to nationalize mines and banks to help the poor. However, after winning the election, they adopted different economic policies. They did not nationalize industries or impose a wealth tax.

Emigration

The period after apartheid saw many skilled white South Africans leave the country due to safety concerns. By 2008, an estimated 800,000 white people had emigrated since 1995. Many moved to Australia, New Zealand, North America, and especially the UK. By 2019, the number of skilled black South Africans emigrating had surpassed white emigrants.

Financial Challenges

The new democratic government inherited a large foreign debt of R86.7 billion (US$14 billion) from the apartheid regime. The government had to repay this debt to avoid financial problems. The debt was finally settled in 2001.

Another challenge was providing antiretroviral (ARV) treatment for people with HIV/AIDS. South Africa had the highest number of people with HIV/AIDS in the world. Providing ARV treatment helped reduce AIDS-related deaths.

Labor Relations

Migrant labor is still a big part of the South African mining industry. In August 2012, police shot and killed 34 striking miners in the Marikana massacre. This incident was widely criticized. The migrant labor system was seen as a main cause of the unrest. Mining companies were accused of not addressing the problems left by apartheid.

Poverty and Protests

In 2014, about 47% of South Africans, mostly black, lived in poverty. This makes South Africa one of the most unequal countries. Many people were unhappy with the slow pace of change and government problems. This led to many violent protests. By 2014, almost 80% of protests involved violence.

Corruption Issues

During President Jacob Zuma's time in office, corruption became a growing problem. There were scandals involving widespread "state capture", where private interests influenced government decisions. This led to financial problems at state-owned companies like Eskom and South African Airways. The Zondo Commission of Inquiry was appointed to investigate these corruption claims.

Energy Crisis

Since 2007, South Africa has faced an ongoing energy crisis. This has hurt the economy and job creation. The state-owned power company, Eskom, has had problems with corruption and mismanagement.

Xenophobia

The period after apartheid has seen many outbreaks of xenophobic attacks against foreign migrants and asylum seekers from other African countries. A 2006 study found that South Africans showed high levels of xenophobia. The UN Refugee Agency found that competition over jobs, businesses, and services caused tension and violence. Many refugees and asylum seekers came from Zimbabwe, Burundi, Congo, Rwanda, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Somalia.

2021 Civil Unrest

Civil unrest happened in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng provinces in July 2021. It started after former President Jacob Zuma was imprisoned for not testifying at a corruption inquiry. Protests turned into widespread rioting and looting. This was made worse by job losses and economic problems from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Economist called it the worst violence in South Africa since apartheid ended. Police and military were sent to stop the unrest. By July 18, over 3,400 people were arrested, and by July 22, 337 people had died.

Post-Apartheid Leaders

Under the new Constitution, the president is the head of both state and government. The president is elected by the National Assembly and can serve a maximum of two terms.

| President | Term of office | Political party | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Portrait | Name | Took office | Left office | Duration | |

| 1 |  |

Nelson Mandela (1918–2013) |

10 May 1994 | 16 June 1999 | 5 years, 37 days | African National Congress |

| 2 |  |

Thabo Mbeki (1942–) |

16 June 1999 | 24 September 2008 (resigned) |

9 years, 100 days | African National Congress |

| 3 |  |

Kgalema Motlanthe (1949–) |

25 September 2008 | 9 May 2009 | 226 days | African National Congress |

| 4 |  |

Jacob Zuma (1942–) |

9 May 2009 | 14 February 2018 (resigned) |

8 years, 264 days | African National Congress |

| 5 |  |

Cyril Ramaphosa (1952–) |

15 February 2018 | Present | 8 years, 5 days | African National Congress |

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Sudáfrica para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Sudáfrica para niños

- Freedom Day (South Africa)

- History of Africa

- Scramble for Africa

- History of Cape Colony

- History of Johannesburg

- History of the Northern Cape

- History of South African wine

- List of presidents of South Africa

- List of prime ministers of South Africa

- List of heads of state of South Africa

- List of South Africa-related topics

- Military history of South Africa

- Politics of South Africa

- Timeline of South Africa

- Timeline of liberal parties in South Africa

- Years in South Africa

- History of cities in South Africa:

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |