Paul Kruger facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Paul Kruger

|

|

|---|---|

Kruger c. 1890

|

|

| 5th State President of the South African Republic | |

| In office 9 May 1883 – 31 May 1902 |

|

| Vice President |

|

| Preceded by | Triumvirate |

| Succeeded by | Schalk Willem Burger (acting) |

| Member of the Triumvirate | |

| In office 8 August 1881 – 9 May 1883 Serving with Marthinus Pretorius and Piet Joubert

|

|

| Preceded by | Thomas Burgers (as President) |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger

10 October 1825 Steynsburg, Cape Colony (now South Africa) |

| Died | 14 July 1904 (aged 78) Clarens, Switzerland |

| Resting place | Heroes' Acre, Pretoria |

| Height | 170 cm (5 ft 7 in) |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 18 |

| Signature | |

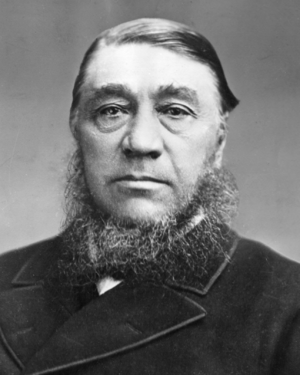

Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger (10 October 1825 – 14 July 1904), known as Paul Kruger, was a famous South African politician. He was a major political and military leader in 19th-century South Africa. From 1883 to 1900, he served as the State President of the South African Republic, also known as the Transvaal.

His nickname was "Oom Paul" (Afrikaans for 'Uncle Paul'). He became famous around the world as the face of the Boer cause. The Boers were Dutch-speaking settlers in South Africa. Kruger led the Transvaal and its neighbor, the Orange Free State, in their fight against Britain during the Second Boer War (1899–1902). Many people see him as a symbol of the Afrikaner people and a tragic folk hero.

Contents

Early Life and the Great Trek

Paul Kruger was born on 10 October 1825, in the Cape Colony, which was then part of the British Empire. His family were Afrikaners, who were farmers of Dutch, German, and French background. Kruger had very little formal schooling. He learned to read and write, but the main book he studied was the Bible.

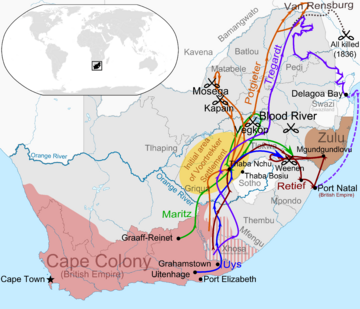

In the 1830s, many Boers were unhappy with British rule. They decided to leave the Cape Colony and move inland to find new land where they could govern themselves. This mass migration was called the Great Trek. Kruger was just a boy when his family joined the trek.

The journey was dangerous. The migrating Boers, called Voortrekkers, often fought with native African tribes over land. When he was 11, Kruger took part in the Battle of Vegkop. A small group of Boers defended their camp, a circle of wagons called a laager, from thousands of Ndebele warriors.

Later, his family moved to the region of Natal. After conflicts with the Zulu king Dingane, they returned to the high plains and settled in the area that would become the Transvaal.

A Rising Leader

As a young man, Kruger became known as a skilled frontiersman and fighter. When he was 16, he was given his own farm. At 17, he was elected to a junior leadership position called a deputy field cornet.

In 1852, Kruger was present when the Voortrekker leader Andries Pretorius signed the Sand River Convention with Great Britain. This was a very important agreement. In it, Britain recognized the independence of the Boers living in the Transvaal. This new country was called the South African Republic.

Over the next 20 years, Kruger helped build the new republic. He became a commandant in the army and helped settle disputes between different Boer groups. By 1863, he was elected Commandant-General, the head of the republic's army. He was a very religious man and believed that God guided his life.

British Rule and the First Boer War

In 1877, Britain decided to take control of the Transvaal, hoping to unite all of South Africa under its rule. The British annexed the territory, and the South African Republic lost its independence. Kruger was appointed vice president just before this happened.

Kruger was determined to get his country's freedom back. He led two groups, called deputations, to London to protest the annexation. He argued that Britain had broken the Sand River Convention. However, the British government refused to change its mind.

Back in the Transvaal, the Boers became more united against British rule. In 1880, they declared their independence again, and the First Boer War began. Kruger was one of three leaders in a triumvirate that governed the republic. The Boers, who were excellent marksmen and knew the land well, won several key battles.

The war ended in 1881 after the Boer victory at the Battle of Majuba Hill. Britain agreed to recognize the republic's independence again, but under British "suzerainty," which meant Britain still had some control over its foreign affairs.

President of the South African Republic

In 1883, Paul Kruger was elected president of the South African Republic. One of his first goals was to get full independence from Britain. In 1884, he led a third deputation to London. This resulted in the London Convention, which removed the term "suzerainty" and gave the republic more freedom.

The Gold Rush and Newcomers

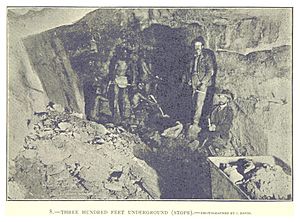

In 1886, gold was discovered on a farm in the Transvaal. This led to the Witwatersrand Gold Rush, and thousands of people from Britain and other countries rushed to the area. These newcomers were called uitlanders (foreigners). The city of Johannesburg grew very quickly.

The gold mines made the South African Republic very wealthy. However, the uitlanders created a problem for Kruger. They paid most of the country's taxes but were not allowed to vote or have a say in the government.

Kruger worried that if he gave the uitlanders the right to vote, they would outnumber the Boers. He feared this could lead to the country being taken over by Britain. This disagreement over the rights of uitlanders caused a lot of tension.

Tensions with Britain

The British government, especially powerful figures like Cecil Rhodes, wanted the uitlanders to have more rights. In 1895, a British man named Leander Starr Jameson led a small, armed force into the Transvaal. This event, known as the Jameson Raid, was meant to start an uprising among the uitlanders.

The raid failed completely. Jameson and his men were captured. Kruger handled the situation wisely. Instead of punishing the raiders harshly, he handed them over to the British authorities. This made him look like a reasonable leader and won him support, but it also made the relationship with Britain much worse.

The Second Boer War

The tensions between the South African Republic and Britain continued to grow. The British government demanded full voting rights for uitlanders who had lived in the country for five years. Kruger offered a seven-year period, but negotiations failed.

In October 1899, Kruger's government issued an ultimatum to Britain, demanding that it remove its troops from the border. Britain refused, and the Second Boer War began. The Orange Free State fought alongside the Transvaal.

The war was much longer and more difficult than the first one. At first, the Boer commandos had some success. But the British Empire sent a huge army to South Africa. By 1900, British forces had captured the republic's major cities, including the capital, Pretoria.

Kruger, who was now 74 years old, had to flee. The Boer leaders decided he should go to Europe to try to get help for their cause.

Final Years in Exile

In September 1900, Paul Kruger left South Africa for the last time. He traveled to Europe on a Dutch warship. He was welcomed by huge, cheering crowds in France, but he failed to get any military help from European governments.

He spent the rest of his life in exile, living in the Netherlands and later in Switzerland. His wife, Gezina, died in South Africa in 1901. The Second Boer War ended in 1902 with a British victory. The South African Republic and the Orange Free State became British colonies.

Paul Kruger died in Clarens, Switzerland, on 14 July 1904, at the age of 78. His body was brought back to South Africa, where he was given a state funeral and buried in the Heroes' Acre cemetery in Pretoria.

Legacy

Paul Kruger is remembered as one of the most important figures in South African history. To many Afrikaners, he is a hero who fought for the freedom and independence of his people. Others see him as a stubborn leader who resisted change.

His legacy can still be seen today. The world-famous Kruger National Park, a huge wildlife reserve, is named after him. His face is on the Krugerrand, a gold coin made in South Africa. His former home in Pretoria is now a museum.

Images for kids

-

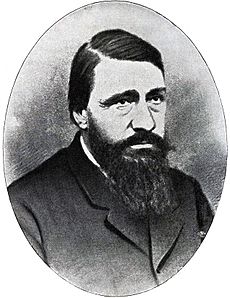

Piet Joubert, Kruger's partner in the second delegation

-

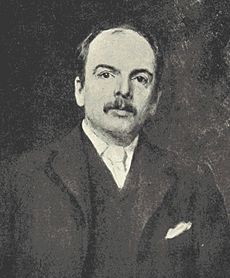

Sir Garnet Wolseley, who led the British Transvaal administration from 1879 to 1880

-

Piet Cronjé, pictured later in life

-

Lord Derby, with whom the third delegation made the London Convention

-

Bismarck, one of the many European leaders Kruger met in 1884

-

President Francis William Reitz of the Orange Free State

-

Joseph Chamberlain, the British Colonial Secretary

-

Leander Starr Jameson, leader of the Jameson Raid into the Transvaal in 1895–96

-

Jan Smuts, Kruger's State Attorney from 1898

-

Sir Alfred Milner, the British High Commissioner for Southern Africa

-

Oranjelust, Kruger's home in Utrecht, photographed in 1963

-

The famous Kruger National Park in Limpopo was named after him

See also

In Spanish: Paul Kruger para niños

In Spanish: Paul Kruger para niños