Jameson Raid facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Jameson Raid |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Boer Wars | |||||||

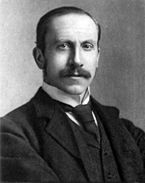

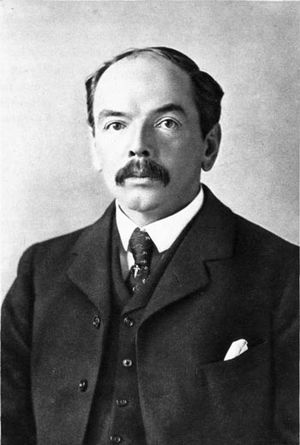

Cecil Rhodes and Alfred Beit, instrumental in the Jameson Raid |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 18 killed 40 wounded |

4 killed 5 wounded |

||||||

The Jameson Raid was a failed attack against the South African Republic (also known as the Transvaal). It happened from December 29, 1895, to January 2, 1896. A British colonial leader named Leander Starr Jameson led about 500 police officers from Rhodesia. He worked for Cecil Rhodes, a very powerful British businessman.

The main goal of the raid was to start an uprising by British workers living in the Transvaal. These workers were called Uitlanders. However, the plan did not work, and no uprising happened. The raid caused a lot of trouble. The British government was embarrassed. Cecil Rhodes had to step down as prime minister of the Cape Colony. Also, the Boers, who were Dutch settlers, became even stronger in the Transvaal and controlled its gold mines. The Jameson Raid was one of the reasons for the Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902).

Contents

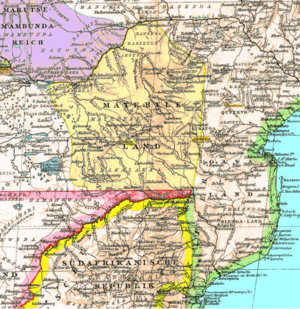

South Africa's Past

In the late 1800s, the area we now call South Africa was not one country. It was split into four main parts. There were two British colonies: the Cape Colony and Natal. There were also two independent republics run by the Boers: the Orange Free State and the South African Republic (Transvaal).

How Colonies and Republics Started

The first Europeans settled in the Cape area, near today's Cape Town, in 1652. These early settlers were Dutch and worked for the Dutch East India Company. Over the next 150 years, the Dutch expanded their control.

But by the early 1800s, Dutch power was fading. In 1806, Great Britain took over the Cape. They wanted to stop Napoleon from getting it and to control important trade routes to the Far East.

Many Boers did not like British rule. They disliked the new rules and systems. One big problem was how Britain dealt with slavery in South Africa. In 1828, a British law said everyone should be treated equally, no matter their race. In 1830, a new law punished people who treated slaves badly. This made many Boers angry.

Then, in 1834, Britain ended slavery across its whole empire. The Boers did not agree with this. They felt their farms needed enslaved labor. They also thought they would not get enough money for their freed slaves. Because of this anger, many Boers decided to leave British rule. They moved into new, unsettled lands. This big move was called the Great Trek.

Not all Boers left. Many in the Western Cape stayed. But the Trekboers, who were frontier farmers, moved further away. These travelers, known as Voortrekkers, first went east to what became Natal. In 1839, they created the Natalia Republic. Other Voortrekkers moved north, settling near the Orange and Vaal rivers.

Britain did not want its people moving beyond its control. So, in 1843, Britain took over the Natalia Republic. It became the British colony of Natal. After 1843, Britain mostly stopped trying to expand in South Africa. But they did try to take over some northern areas. Still, Britain recognized the independence of the Transvaal in 1852 and the Orange Free State in 1854. This was done through agreements called the Sand River Convention and the Orange River Convention.

After the First Anglo-Boer War, the British government gave the Transvaal its independence back in 1884. This was agreed in the London Convention. No one knew then that huge gold deposits would be found there two years later.

Money and Resources

Even though the four territories were politically separate, they were connected. Many people had family or friends in other areas. The Cape Colony was the largest and oldest. It was the most important in terms of money, culture, and society. People in Natal and the Boer republics were mostly farmers.

This simple farming life changed in 1870. Huge diamond fields were found near modern-day Kimberley. This area had been under the Orange Free State. But the Cape government, with British help, took it over.

The Discovery of Gold

In 1884, gold was found at Vogelstruisfontein. Then, in 1886, it became clear there were massive amounts of gold in the Witwatersrand area. This started the Witwatersrand Gold Rush, leading to the city of Johannesburg. Many Uitlanders (foreigners), mostly British, came to find work and fortune.

The discovery of gold made the Transvaal very rich and powerful. But it also attracted so many Uitlanders that they soon outnumbered the Boers. By 1896, there were about 60,000 Uitlanders and 30,000 white male Boers.

The Boer government worried about losing its independence to Britain. So, they made strict rules. Uitlanders had to live in the Transvaal for at least four years to get the right to vote. The government also heavily taxed the gold mining industry, which was mostly British and American.

Because of these taxes and lack of voting rights, the Uitlanders became very angry. President Paul Kruger and his advisors discussed the problem. They decided to put a heavy tax on dynamite, which was needed for mining. This tax made the Uitlanders even more upset. As Johannesburg was mainly an Uitlander city, their leaders started talking about a rebellion.

Cecil Rhodes, the Governor of the Cape, wanted to unite the Transvaal and Orange Free State under British control. He and Alfred Beit had formed a huge mining company, De Beers Mining Corporation. They also wanted to control the gold mines in Johannesburg. They played a big role in making the Uitlanders' complaints worse.

Rhodes believed that if he didn't get involved, the Uitlanders would rebel on their own. He feared this would create a new republic that was against Britain. To stop this, he decided to act.

In mid-1895, Rhodes planned a raid. An armed group from Rhodesia, a British colony to the north, would support an Uitlander uprising. The goal was to take control of the Transvaal. But the plan quickly ran into problems. The Uitlander leaders in Johannesburg were not sure about the uprising.

The Drifts Crisis

In September and October 1895, a dispute happened between the Transvaal and Cape Colony. The Cape Colony refused to pay high fees for using the Transvaal railway line to Johannesburg. Instead, they sent goods by wagon across a set of river crossings called 'drifts'. Transvaal President Paul Kruger closed these drifts. This angered the Cape Colony government. Even though Transvaal eventually reopened them, relations remained tense.

Jameson's Force and the Raid

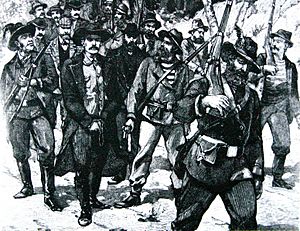

As part of the plan, a force was gathered at Pitsani, near the Transvaal border. Cecil Rhodes ordered this force to be ready to help the Uitlanders. Leander Starr Jameson was in charge of this group. He was a leader in Rhodes's British South Africa Company. The force had about 600 men, with rifles, machine guns, and some artillery.

The plan was for Johannesburg to rebel and seize the Boer weapons in Pretoria. Then, Jameson and his force would rush to Johannesburg to "restore order." By controlling Johannesburg, they would control the gold fields.

However, the Uitlander leaders in Johannesburg had disagreements. They were not ready to start the uprising. Some even told Jameson to wait. But Jameson became impatient. He had 600 restless men. He believed he could make the Johannesburg reformers act. So, he decided to go ahead.

On December 28, 1895, Jameson sent a telegram to Rhodes, saying he would leave the next evening unless told otherwise. The next day, he sent another message saying he would leave that night. But the first telegram was delayed, so both arrived at the same time on December 29. By then, Jameson's men had cut the telegraph wires, and no one could stop him.

On December 29, 1895, Jameson's armed group crossed into the Transvaal. They headed for Johannesburg. They hoped to reach Johannesburg in three days, before the Boer soldiers could get ready. They also hoped it would start the Uitlander uprising.

The British Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain, wanted the raid to succeed in the end. But he knew it was a mistake to start it without the Uitlanders' support. He immediately tried to stop it. He rushed back to London and ordered the governor-general of the Cape Colony, Sir Hercules Robinson, to say that Jameson's actions were wrong. Chamberlain also warned Rhodes that his company's charter was at risk if he was involved. He told British colonists not to help the raiders.

Jameson's men had cut the telegraph wires to Cape Town. But they failed to cut the wires to Pretoria. So, news of their invasion quickly reached Pretoria. Transvaal forces tracked Jameson's group from the start.

On January 1, Jameson's group had a brief fight with a Boer outpost. Around noon, they reached Krugersdorp. A small group of Boer soldiers had blocked the road to Johannesburg. Jameson's force fought the Boers for hours, losing men and horses. Towards evening, they tried to go around the Boer force. But the Boers followed them. On January 2, a large Boer force with artillery was waiting for Jameson at Doornkop. The tired raiders fought, losing about thirty men. Jameson realized it was hopeless and surrendered to Commandant Piet Cronjé. The raiders were taken to Pretoria and put in jail.

What Happened Next

The Boer government later handed the raiders over to the British for trial. The British prisoners were sent back to London. A few days after the raid, the Kaiser of Germany sent a telegram to President Kruger. He congratulated Kruger on his success "without the help of friendly powers." This hinted at German support. When the British public heard about this, it caused strong anti-German feelings.

Dr. Jameson was seen as a hero by many in the press and London society. People were angry at the Boers and Germans. Jameson was sentenced to 15 months in Holloway for leading the raid. The British South Africa Company paid the Transvaal government almost £1 million in compensation.

The members of the Reform Committee (Transvaal), who conspired with Jameson, were jailed. They were found guilty of a serious crime and sentenced to death. But this sentence was changed to 15 years in prison. In June 1896, they were released after paying large fines. Colonel Frank Rhodes, Cecil Rhodes's brother, was removed from active duty in the British Army. After his release, he joined his brother in the Second Matabele War.

Cecil Rhodes had to resign as Prime Minister of Cape Colony in 1896. This was because of his role in planning the raid. He also resigned as a director of the British South Africa Company, along with Alfred Beit.

Jameson's raid had taken many troops away from Matabeleland. This left the area vulnerable. The Ndebele people, unhappy with the British South Africa Company, revolted in March 1896. This is known as the First Chimurenga in Zimbabwe, or the Second Matabele War. The Shona joined them soon after. Many European settlers were killed. The settlers had to build a defensive camp in Bulawayo. The Ndebele were in their stronghold in the Matobo Hills. It took until October 1897 for the Ndebele and Shona to stop fighting.

Political Effects

In Britain, the Liberal Party did not support the Boer War. Later, Jameson became Prime Minister of the Cape Colony (1904–08). He was also one of the people who helped create the Union of South Africa. He was given a special honor in 1911 and returned to England in 1912. When he died in 1917, he was buried next to Cecil Rhodes and 34 soldiers in the Matobos Hills.

Impact on British-Boer Relations

The raid made relations between the British and Boers very bad. Tensions grew even more because of the "Kruger telegram" from German Kaiser Wilhelm II. He congratulated Kruger on defeating the "raiders." Many saw this as Germany offering military help to the Boers. Wilhelm was already seen as anti-British because he started a costly naval arms race between Germany and Britain.

As tensions rose, the Transvaal started buying many weapons. They also signed an alliance with the Orange Free State in 1897. Jan C. Smuts wrote in 1906 that the Jameson Raid was "the real declaration of war." He meant that even though there was a four-year break, the raid truly started the conflict.

Joseph Chamberlain, the British Colonial Secretary, publicly criticized the raid. But he had approved Rhodes's plans to send armed help if Johannesburg rebelled. In London, some newspapers condemned the raid. But most used it to stir up anti-Boer feelings. Even though Jameson and his raiders faced charges, many people saw them as heroes. Chamberlain welcomed the increased tensions as a chance to take over the Boer states.

See also

- Drifts Crisis

- Military history of South Africa

- Second Boer War

- Second Matabele War

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |