Francis William Reitz facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Francis William Reitz

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 5th State President of the Orange Free State | |

| In office 10 January 1889 – 11 December 1895 |

|

| Preceded by | Johannes Brand |

| Succeeded by | M.T. Steyn |

| Chief Justice of the Orange Free State | |

| In office June 1876 – 10 January 1889 |

|

| Preceded by | New office |

| Succeeded by | Unknown |

| State Secretary of the South African Republic | |

| In office June 1898 – 31 May 1902 |

|

| Preceded by | W.J. Leyds |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| President of the Senate of the Union of South Africa | |

| In office 1910–1921 |

|

| Preceded by | New office |

| Succeeded by | H.C. van Heerden |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 5 October 1844 Swellendam, Cape Colony |

| Died | 27 March 1934 (aged 89) Cape Town, South Africa |

| Spouses | Blanka Thesen (1854–1887) Cornelia Maria Theresa Mulder (1864–1935) |

| Children | 15 |

| Alma mater | South African College |

| Profession | Lawyer |

Francis William Reitz (born October 5, 1844, in Swellendam – died March 27, 1934, in Cape Town) was an important South African figure. He was a lawyer, politician, and poet. Over his long career, he held many key positions.

Reitz served as a member of parliament in the British Cape Colony. He was also the Chief Justice and later the fifth State President of the Orange Free State. During the Second Boer War, he was the State Secretary of the South African Republic. Later, he became the first president of the Senate of the Union of South Africa.

His career lasted over 45 years and involved four different political areas in South Africa. Reitz trained as a lawyer in Cape Town and London. He played a big part in making the legal system and government of the Orange Free State more modern. He was also active in promoting the Afrikaans language and culture.

Reitz was well-liked because of his political ideas and his open personality. When President Johannes Brand died in 1888, Reitz won the election to become president without anyone running against him. After being re-elected in 1895, he became very ill and had to retire. In 1898, after he recovered, he became the State Secretary of the South African Republic. He was a key leader during the Second Boer War. After the war, he chose to live outside South Africa for a while because he didn't want to support the British. He later returned to South Africa and became a lawyer again. In 1910, when the Union of South Africa was formed, Reitz was chosen as the first president of the Senate.

Throughout his life, Reitz was a significant figure in Afrikaner culture. He was especially known for his poems and other writings.

Contents

Reitz's Family Life

Francis William Reitz, Jr. was born in Swellendam on October 5, 1844. His father, Francis William Reitz, Sr., was a politician and a successful farmer. Francis was the seventh of twelve children. He grew up on his father's farm, Rhenosterfontein, in the British Cape Colony.

Reitz was married twice. His first wife was Blanka Thesen, whom he married in Cape Town in 1874. She was from Norway and her family had moved to Knysna. They had seven sons and one daughter. After Blanka passed away in 1887, Reitz married Cornelia Maria Theresia Mulder in 1889. She was from the Netherlands and was a director at a school in Bloemfontein. With his second wife, he had six sons and one daughter. In total, Reitz had 15 children.

One of his sons, Deneys Reitz, was also a very important person. He fought against the British in the Second Boer War. Later, he commanded a military unit in World War I. He also served as a Member of Parliament, a Cabinet Minister, and Deputy Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa. Deneys Reitz wrote a famous book called Commando: A Boer Journal of the Boer War. It is considered one of the best adventure and war stories in English.

Reitz's Education

Reitz first learned at home with a governess and at a nearby farm. When he was nine, he went to Rouwkoop Boarding School in Rondebosch, Cape Town. He was a very good student there. He was chosen as a "Queen's Scholar" by the South African College in Cape Town.

He studied at South African College for six years, starting in 1857. He learned a lot about arts and sciences and became a well-rounded young man with leadership skills. In September 1863, he finished his studies with a degree similar to a modern bachelor's degree.

Reitz became very interested in law. He decided to continue his law studies in London, England, at the Inner Temple. Even though his family's finances were not strong, he went to London and finished his studies successfully. He became a barrister (a type of lawyer) in London on June 11, 1867. While in England, Reitz also became interested in politics and often attended meetings of the British Parliament. Before returning to South Africa, he traveled around Europe. He then started his law practice in Cape Town in January 1868.

Starting His Career

At first, Reitz found it hard to earn a living as a lawyer in Cape Town. There were many lawyers, and competition was tough. However, he soon became known for his sharp legal mind and good social skills. Working with the western Circuit Court of the Cape Colony gave him a lot of experience quickly.

He also pursued his interest in politics by writing articles for the Cape Argus newspaper. He reported on parliamentary meetings and was a deputy editor. In 1870, Reitz moved his law practice to Bloemfontein in the Orange Free State. He thought the discovery of diamonds nearby would bring more legal work. But this didn't happen, so after a few months, he tried to become a diamond prospector in Griqualand West. This also didn't work out.

After these attempts, Reitz returned to Cape Town. This time, his law practice there was successful. This was partly because the British took over the diamond fields of the Orange Free State in 1871, which brought economic growth to the Cape Colony.

In 1873, Reitz was asked to represent the Beaufort West district in the Cape Parliament. On the day he took his seat, his father, who was also a politician, announced his retirement. Reitz's time in parliament was short. Just two months later, President Johannes Brand of the Orange Free State offered him a job as chairman of their new Appellate court. Reitz initially refused because he felt he wasn't fully qualified and was too young. But President Brand insisted, and the Volksraad (parliament) agreed to appoint him.

Judge in the Orange Free State

When Reitz became a judge in the Orange Free State, he truly found his calling. He arrived in Bloemfontein in August 1874, at nearly 30 years old and newly married. This marked the start of 21 years living there and a very successful career. It would eventually lead to him being elected as State President.

Before the mid-1870s, the Orange Free State's legal system was not very organized. Many judges were not properly trained in law. Reitz's first job was to improve this. He worked hard, and within a year, the Volksraad passed a law creating a professional Circuit Court and a Supreme court. Reitz became the first president of the Supreme Court and the first Chief Justice of the Orange Free State.

Reitz was a strong leader. He sometimes disagreed with the Volksraad to modernize the legal system. He also fought to get better salaries and pensions for government officials. As someone born in the Cape Colony, he had to earn the trust of the Boer people. He did this by traveling with the Circuit Court for over ten years. This helped him understand their way of life and their strong religious beliefs. Reitz himself was religious and grew up in the Afrikaans-speaking countryside, which also helped. He eventually became a symbol of Afrikaner identity for many people in the Orange Free State.

Reitz did a lot to organize and review the laws of the Orange Free State. In 1877, he and his colleagues published the first Ordonnantie boek van den Oranje Vrijstaat (Ordinance Book of the Orange Free State). This made the republic's laws available to everyone. He also helped revise the Orange Free State's constitution, especially regarding citizenship and voting rights. He worked to improve the prison system and how districts were managed.

State President of the Orange Free State

As early as 1878, people wanted Reitz to run for president. However, President Brand was still very popular, and Reitz openly praised him and refused to run against him. In the late 1870s and early 1880s, politics in the Orange Free State became very intense. The British taking over the South African Republic (Transvaal) in 1877, and the First Anglo-Boer War (1880–1881) where the Transvaal regained its freedom, greatly affected people's feelings.

Some people wanted to be careful in their relationship with the British. Others wanted to strongly promote a new Afrikaner national identity. Reitz was part of this second group. With C.L.F. Borckenhagen, a newspaper editor, he wrote a constitution for the Afrikaner Bond (Afrikaner Union). This was a political party started by leading Afrikaner politicians in the Cape Colony. Reitz became the chairman of the Bond several months later. His open political activities drew criticism from those who feared problems with the British. However, it was clear that a big change was happening among the Boer republics and Afrikaners in the Cape Colony, which would greatly change relations with the British.

President Brand in the Orange Free State wanted to keep a careful and neutral policy towards the British. He was even given a British knighthood for this. Despite the changing political mood, Brand remained very popular. The 1883 presidential elections could have been a big fight between supporters of the Afrikaner Bond and Brand's followers. But Reitz, who would have been the ideal candidate for the Bond, again refused to run against Brand.

Only when Brand died in office five years later was the time right for change. Reitz ran for president and won by a huge margin, supporting Afrikaner nationalism. He officially became state president in Bloemfontein on January 10, 1889.

As president, Reitz was one of the first Afrikaners to actively develop a "Bantu policy." This was a new way of thinking about the relationship between white and black people. Under his government, a law was passed in 1890 that stopped Indian immigrants from settling in the Orange Free State. This caused a disagreement with the British government. Reitz had a lot of communication with the British high commissioner in Cape Town, where he strongly stated that the Orange Free State was an independent state.

Economically, the late 1880s were a time of growth for the Orange Free State. Farming improved, and the railway system became an important source of money. Reitz helped modernize farming by promoting new techniques and a scientific approach to preventing diseases. In this, Reitz showed he was a good farmer, just like his father.

During Reitz's presidency, a new meeting hall for the Volksraad, called the Vierde Raadszaal (Fourth Council Hall), was opened in 1893. The main Government Building also got a second floor in 1895. Outside Bloemfontein, the roads were improved.

As expected, right after becoming president, Reitz contacted the government of the South African Republic (Transvaal) to create closer political ties. On March 4, 1889, the Orange Free State and the South African Republic signed a treaty to defend each other. Treaties about trade and railways followed. Even earlier, in January 1889, the Volksraad asked Reitz to negotiate a customs treaty with both the British South African colonies and the South African Republic. A Customs Conference was held in Bloemfontein on March 20, 1889. This led to an agreement between the Orange Free State and the Cape Colony that was very good for the Orange Free State.

Economic benefits grew even more when new railway lines opened. These connected the Cape Colony to Bloemfontein (1890) and Bloemfontein to Johannesburg (1892). This directly linked Cape Town with Johannesburg and made the Orange Free State a transit economy (meaning goods passed through it). For Reitz, developing a unified South African railway system was also a political goal. He saw railways as a way to reduce distrust and create unity among the white people of South Africa.

The Volksraad liked Reitz's policies. This showed the shift in the Afrikaner voters' mood towards Afrikaner nationalism. Months before the 1893 presidential election, the Volksraad supported Reitz's re-election by a vote of 43 to 18. Reitz accepted, but only if he could have three months' leave to Europe. On November 22, 1893, he was re-elected with another large majority.

His trip to Europe was more than just a family holiday. In Britain, Reitz made strong public statements. He defended the republican system of government in South Africa. He also spoke against British interference in "Bantu affairs." On the European continent, Reitz met with several heads of state and political leaders. He returned to Bloemfontein in October 1894. Soon after, Reitz was diagnosed with hepatitis, which also affected his nerves and caused sleeplessness. His condition was so serious that he had to resign from the presidency. The Volksraad accepted his resignation on December 11, 1895.

In June 1896, Reitz traveled to Europe again for five months to recover from his illness. When he returned to South Africa, he settled in Pretoria in the South African Republic in July 1897. There, he started a new law practice.

State Secretary of the South African Republic

Reitz did not remain a private citizen for long. A disagreement between the South African Republic's government and its judiciary led to the dismissal of the Chief Justice. Reitz was then appointed as a judge in early 1898. He quickly became part of the inner circle of the Transvaal government. At this time, relations with the British were getting worse quickly. The government of the South African Republic was trying to strengthen its position both nationally and internationally.

One step they took was to replace the State Secretary, Willem Johannes Leyds, who was Dutch, with a South African. Leyds was appointed to represent the Republic in Europe. Reitz took his place as State Secretary in June 1898.

As State Secretary, Reitz had a very difficult and important job. After the State President, he was the most important member of the Executive Council. As the top civil servant, he was in charge of making sure laws and rules were followed. He also handled all the President's letters and official government reports. He was a link between the Executive Council and parliament (the First and Second Volksraad). He was also a key figure in the State's foreign affairs. Reitz was experienced and well-organized. He quickly modernized the government structure. He set up rules for how government departments should run. He also made it a rule that all communication with the government should be in Dutch.

The State President of the South African Republic, Paul Kruger, was not an easy person to work with. Some people thought Reitz would quickly be controlled by Kruger. But this was not the case. Sometimes, the two men disagreed on policies, but Reitz stuck to his beliefs. He even gained some influence over Kruger. The British first praised Reitz for his polite diplomacy. But their attitude quickly changed when they realized Reitz strongly supported Transvaal's independence. Reitz was sometimes very bold in his political statements. For example, when he claimed the South African Republic was a fully independent state, the British strongly reacted.

British pressure was growing fast, and an armed conflict was coming. This was about the position of the Uitlanders (foreigners) and economic control over the Witwatersrand gold fields. Foreign policy in the South African Republic was eventually decided by three key figures: State President Kruger, State Secretary Reitz, and State Attorney General Jan Smuts. In 1899, they decided that a strong stance against British demands was the only way forward, even with the risks. Reitz got the support of the Orange Free State for this approach. On October 9, 1899, the South African Republic and the Orange Free State issued a joint ultimatum to the British government to withdraw their demands.

The British government did not agree to the ultimatum. Two days later, on October 11, 1899, the Second Anglo-Boer War (also called the South African War) began. When the British army marched on Pretoria in May 1900, the government had to flee the capital. From that moment on, Reitz was responsible for moving the government's location throughout the Transvaal. This happened 62 times until March 1902. In May of that year, Reitz actively took part in the peace talks with the British. He was one of the people who signed the Treaty of Vereeniging, which was signed in Pretoria on May 31, 1902.

Living Abroad and Returning to Politics

Even though Reitz helped write the Treaty of Vereeniging, he personally did not want to promise loyalty to the British government. So, he chose to go into exile. On July 4, 1902, he left South Africa and joined his wife and children in the Netherlands. To help with his money problems, Reitz went on a lecture tour in the United States. However, people's interest in the Boer cause had faded since the war ended, so the tour failed. Reitz had to return to the Netherlands. There, his health got worse again, leading to him being hospitalized and needing a long time to recover. His friends W.J. Leyds and H.P.N. Muller, along with the Dutch South-African Society, supported him.

In 1907, after the old Boer republics gained self-government, and before the Union of South Africa was formed, important Afrikaner politicians J.C. Smuts and L. Botha asked Reitz to return to South Africa and get involved in politics again. He and his wife settled in Sea Point, Cape Town. In 1910, at 66 years old, he was appointed president of the Senate of the newly formed Union of South Africa.

These years were not easy. Former Afrikaner friends found themselves on different sides of politics in a fast-changing world. Just like earlier in his life, Reitz remained a man with strong opinions, which he shared freely. Because of this, he came into conflict with the Smuts government. In 1920, he was not re-appointed as president of the Senate. However, he remained a member of the Senate until 1929.

Honors and Passing Away

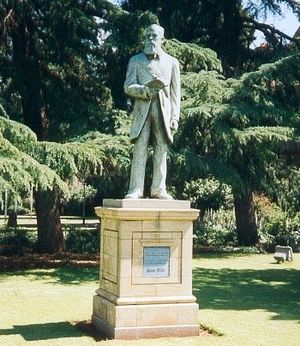

As an important public figure, Reitz was honored in different ways. In 1923, the University of Stellenbosch gave him an honorary doctorate in law for his public service. Earlier, in 1889, a village in the Orange Free State was named after him. In 1894, another village was named after his second wife, Cornelia. A ship named after him, the President Reitz, sank off Port Elizabeth in 1947. The Jubilee Diamond, found in 1895, was first called the Reitz Diamond. But it was renamed in 1897 to honor Queen Victoria's 60th anniversary as queen.

When he finally retired from public life, Reitz moved to Gordon's Bay. But he returned to Cape Town several years later. He lived in Tamboerskloof and was cared for by his daughter Bessie, who was a medical doctor. He continued writing and translating until the end of his life. Reitz passed away at his home on March 27, 1934. He received a state funeral three days later, with a service at the Grote Kerk. He was buried at the Woltemade cemetery in Maitland.

Cultural Impact

Reitz was a very important person in Afrikaner culture. He was a poet and published many poems in Afrikaans. This made him a pioneer in developing Afrikaans as a cultural language. He supported the Genootskap van Regte Afrikaners (Society of Real Afrikaners), which was formed in the Cape Colony in 1875. Even though he never officially joined, he actively wrote for the society's journal, Die Suid-Afrikaansche Patriot.

With his writing, Reitz was a key part of the First Afrikaans Language Movement. He was more interested in writing in Afrikaans for cultural reasons than for teaching purposes. Much of his work was based on English texts, which he translated, edited, and changed. In doing so, he created completely new works of art.

For Reitz, Afrikaans was mainly a language for culture, not for government. In government, he promoted the use of Dutch, which was the official language of the Boer republics. During his time as president of the Orange Free State, where many people used English, he strongly encouraged the use of Dutch. He did this even when politicians like John G. Fraser preferred English.

Reitz also helped establish the Letterkundige en Wetenschappelijke Vereeniging (Literary and Scientific Society) of the Orange Free State, where he was chairman for a while. He also supported the library in Bloemfontein and the National Museum of the Orange Free State.