F. W. de Klerk facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

F. W. de Klerk

OMG DMS

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

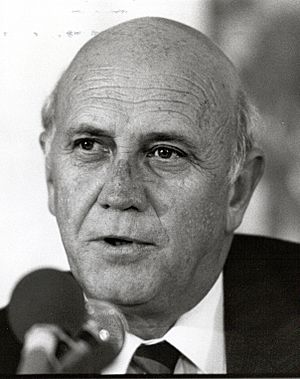

de Klerk in 1990

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7th State President of South Africa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 14 August 1989 – 10 May 1994 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | P. W. Botha | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Nelson Mandela (as President) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1st Deputy President of South Africa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 May 1994 – 30 June 1996 Serving with Thabo Mbeki

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | Nelson Mandela | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Alwyn Schlebusch (as Vice State President) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Thabo Mbeki (solely) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13th Leader of the Opposition | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 1996–1997 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | Nelson Mandela | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Constand Viljoen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Marthinus van Schalkwyk | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7th President of the National Party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 15 August 1989 – 8 September 1997 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | P. W. Botha | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Marthinus van Schalkwyk (Leader, New National Party) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

Frederik Willem de Klerk

18 March 1936 Johannesburg, Transvaal, Union of South Africa |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 11 November 2021 (aged 85) Cape Town, Western Cape, Republic of South Africa |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | NP (1972–1997) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other political affiliations |

NNP (1997–2005) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouses |

Marike Willemse

(m. 1959; div. 1996)Elita Georgiades

(m. 1999) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parent |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Potchefstroom University (BA, LLB) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Profession | Attorney | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Frederik Willem de Klerk (born 18 March 1936 – died 11 November 2021) was a South African politician. He served as the last state president of South Africa from 1989 to 1994. He was also a deputy president from 1994 to 1996.

De Klerk led the National Party from 1989 to 1997. He is known for ending the apartheid system. Apartheid was a system of racial segregation that separated people by race. It gave white South Africans more rights than others. De Klerk and his government worked to introduce universal suffrage, which means all adult citizens can vote.

He was born in Johannesburg into an important Afrikaner family. He studied law at Potchefstroom University. He then joined the National Party and became a Member of Parliament. He held several government jobs under President P. W. Botha.

When Botha resigned in 1989, de Klerk became the leader. Many people thought he would continue apartheid. But de Klerk decided to end it. He saw that growing conflict could lead to a civil war. He allowed anti-apartheid protests and made banned political parties legal again. He also freed jailed anti-apartheid leaders like Nelson Mandela.

De Klerk worked with Mandela to end apartheid and create a new, fair government. In 1993, he said sorry for the harm caused by apartheid. He oversaw the 1994 election, where everyone could vote. Mandela's African National Congress (ANC) won, and de Klerk's party came second.

He then became Deputy President in Mandela's government. He supported the government's economic plans. But he disagreed with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. This group investigated past human rights abuses. De Klerk wanted a full pardon for political crimes. His relationship with Mandela was often difficult. In 1996, his party left the government. He retired from politics in 1997.

De Klerk was a complex figure. He won the Nobel Peace Prize for ending apartheid. But some anti-apartheid activists criticized him. They felt he did not fully apologize for apartheid's wrongs. They also felt he did not address human rights abuses by state forces. Some Afrikaners also criticized him. They felt he betrayed their interests by ending apartheid.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Growing Up in South Africa

Frederik Willem de Klerk was born on 18 March 1936 in Mayfair, a suburb of Johannesburg. His parents were Johannes "Jan" de Klerk and Hendrina Cornelia Coetzer. He was the second son in his family. His first language was Afrikaans. His family had been in South Africa since the late 1680s.

De Klerk had a safe and comfortable childhood. His family was important in Afrikaner society. They had strong ties to South Africa's National Party. His father, Jan de Klerk, was a senator and a cabinet member for many years. This meant de Klerk grew up surrounded by politics. His older brother, Willem, often challenged his more traditional views. Willem later became a political analyst.

The name "de Klerk" comes from French Huguenot origins. It means "clergyman" or "literate." De Klerk also had Dutch and Indian ancestors. He was also said to be related to the Khoi interpreter named Krotoa.

When de Klerk was twelve, the apartheid system became official. His father was one of its creators. So, de Klerk grew up with the idea of apartheid. He learned the customs and values of Afrikaner society. He was raised in the Gereformeerde Kerk, a conservative Dutch Reformed Church.

His family moved often, so he changed schools many times. He finished high school in 1953 at the Hoërskool Monument in Krugersdorp.

University and Law Career

From 1954 to 1958, de Klerk studied at Potchefstroom University. He earned degrees in Arts and Law. He learned to think about legal principles. At university, he edited the student newspaper. He was also a leader in student groups. He joined the Broederbond, a secret society for Afrikaner leaders. He played tennis and hockey.

At university, he met Marike Willemse. They married in 1959. After university, de Klerk became a lawyer. He opened his own law firm in Vereeniging, Transvaal, in 1962. He built it into a successful business over ten years. During this time, he was involved in many community activities.

Starting His Political Journey

In 1972, de Klerk was offered a law teaching job at his old university. But he was also asked to run for the National Party in Vereeniging. He chose politics and was elected to the House of Assembly in November. He quickly became known as a strong debater.

He took on many roles in the party. He was in charge of the Transvaal National Party's information. He also helped start a new youth movement for the party. He visited other countries like Israel, West Germany, the UK, and the US. In 1976, in the US, he felt he saw more racism there than in South Africa.

In 1978, de Klerk became the Minister of Social Welfare and Pensions. He later served as Minister of Post and Telecommunications and Minister of Mining. As Minister of the Interior, he helped end the Mixed Marriages Act. This law had forbidden marriages between different races.

In 1981, he received an award for his government work. As education minister from 1984 to 1989, he supported the apartheid system in schools. For most of his career, de Klerk was seen as a very traditional politician. He strongly supported apartheid and white minority interests.

Becoming State President

P. W. Botha resigned as leader of the National Party in 1989. De Klerk was elected to replace him on 2 February 1989. He won by a small number of votes. Soon after, he suggested a new South African constitution. He hinted it would give more rights to non-white groups. He also met with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. She urged him to free Nelson Mandela.

Ending Apartheid

Botha resigned as State President on 14 August 1989. De Klerk became acting president. He was then elected president for a full five-year term on 20 September. At first, many anti-apartheid leaders thought he would be like past presidents. Desmond Tutu said he didn't expect much change.

But de Klerk surprised everyone. He allowed anti-apartheid marches to happen. He said, "the door to a new South Africa is open." This was a big change from Botha's time. He also allowed secret talks between his intelligence service and ANC leaders. In October, he met with Tutu and other activists. He also released some older anti-apartheid prisoners.

On 2 February 1990, de Klerk announced major reforms to parliament. He legalized banned political parties, including the ANC and the Communist Party. He also announced that Nelson Mandela would be freed. Mandela was released a week later. De Klerk also ended the Separate Amenities Act, which had segregated public places. His goal was for South Africa to become a liberal democracy with a free market economy.

People in South Africa and around the world were shocked. Many foreign governments praised de Klerk. Tutu said, "It's incredible... Give him credit." Some white right-wing groups were angry. They felt de Klerk was betraying white South Africans.

More reforms followed. The National Party allowed non-white members. In June, laws that restricted land ownership for black people were repealed. The Population Registration Act, which classified people by race, was also removed. In 1990, de Klerk also ordered an end to South Africa's nuclear weapons program.

Working Towards a New South Africa

De Klerk's presidency focused on talks between his government and the ANC. These talks led to South Africa becoming a democracy. On 17 March 1992, de Klerk held a vote for white South Africans. They voted overwhelmingly to continue talks to end apartheid.

Nelson Mandela sometimes distrusted de Klerk. He believed de Klerk knew about groups trying to cause violence. These groups aimed to stop the talks. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission looked into this, but it was never fully clear.

On 30 April 1993, de Klerk apologized for apartheid. He said, "It was not our intention to deprive people of their rights and to cause misery, but eventually apartheid led to just that. Insofar as to what occurred we deeply regret it... Yes we are sorry." Tutu asked people to accept the apology.

On 10 December 1993, de Klerk and Mandela won the Nobel Peace Prize. They received it for their work in ending apartheid. South Africa held its first election where everyone could vote from 26 to 29 April 1994. The ANC won, and de Klerk became Deputy President under Nelson Mandela.

Serving as Deputy President

De Klerk was sworn in as Deputy President. He was not happy that the ceremony was multi-religious. He preferred it to reflect the leader's faith. He supported the new government's economic plans.

His working relationship with Mandela was often tense. De Klerk found it hard to adjust to not being president. Mandela felt de Klerk was sometimes difficult. They had public disagreements. De Klerk also faced problems within his own party. Some members felt he was ignoring the party.

In May 1996, the National Party was unhappy with the new constitution. They wanted a guarantee of being in government longer. On 9 May, de Klerk pulled the National Party out of the coalition government. He said he would lead the party in opposition. He wanted to ensure South Africa had a strong multi-party democracy.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission

De Klerk was not happy with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). He had hoped for a different setup. He appeared before the TRC to testify. He admitted that security forces used "unconventional strategies" against anti-apartheid groups. But he said he never knew about or approved murder or torture.

When the TRC showed more evidence of abuses, de Klerk said he was shocked. But he insisted he and other senior leaders were not responsible for "criminal actions of a handful of operatives." Tutu questioned how de Klerk could not have known about widespread abuses. Tutu hoped de Klerk would take responsibility. But de Klerk did not.

The TRC found de Klerk had not fully shared information about events during his presidency. This damaged his public image.

Later Years and Legacy

In 1994, de Klerk was elected to the American Philosophical Society. In 1997, he was offered a fellowship at Yale Law School, but he declined due to protests.

In 1999, de Klerk divorced his wife, Marike, after 38 years. He then married Elita Georgiades. This caused some controversy among traditional South Africans. His autobiography, The Last Trek – A New Beginning, was published in 1999.

In 2000, de Klerk started the FW de Klerk Foundation to promote peace. He also chaired the Global Leadership Foundation, which helps democratic leaders.

On 3 December 2001, his former wife, Marike de Klerk, was killed in her home. De Klerk returned from Sweden to mourn. A security guard was arrested and later sentenced for the murder.

In 2005, de Klerk left the New National Party. It merged with the ANC. He remained positive about South Africa's future. In 2006, he had surgery for a serious illness but recovered. He continued to speak about peace and democracy around the world.

De Klerk was an Honorary Patron of the University Philosophical Society of Trinity College Dublin. He also received an award for his work in ending apartheid.

After Jacob Zuma became president in 2009, de Klerk was hopeful about the new government. In a 2012 interview, he spoke about his good relationship with his staff. He also spoke fondly of Nelson Mandela. He said Mandela was "a great unifier" and "the biggest known South African that has ever lived." He attended Mandela's memorial service in 2013.

In 2015, de Klerk wrote to a UK newspaper. He criticized a campaign to remove a statue of Cecil Rhodes. This led to criticism from activists. In 2020, he made a controversial statement about apartheid. His foundation later withdrew the statement.

Illness and Death

On 19 March 2021, it was announced that de Klerk had been diagnosed with cancer. He died from complications of the disease on 11 November 2021, at age 85. He was the last surviving State President of South Africa.

After his death, a video message from de Klerk was released. He apologized "without qualification" for the harm caused by apartheid. He asked South Africans to work together and uphold the constitution.

President Cyril Ramaphosa declared a four-day mourning period for de Klerk. A state memorial service was held in Cape Town on 12 December 2021.

His Beliefs and Personality

De Klerk was seen as a politically conservative figure. But he was also flexible and willing to compromise. He often tried to bring different views together. His brother said he was known for his "soberness, humility and calm." He was honest, intelligent, and open-minded. He was also described as a "team-man" who consulted others.

His former wife said he was "extremely sensitive to beautiful things." His brother Willem said de Klerk was driven by his concern for Afrikaner people. He was upset that many Afrikaners did not realize his reforms aimed to secure their future in South Africa.

De Klerk had three children with Marike: Susan, Jan, and Willem. He was described as a loving father. He was a heavy smoker but quit in 2005. He enjoyed a glass of whisky or wine. He also liked playing golf, hunting, and going for walks.

See also

In Spanish: Frederik de Klerk para niños

In Spanish: Frederik de Klerk para niños