Aljafería facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Aljafería |

|

|---|---|

South east corner

|

|

| General information | |

| Location | Zaragoza, Spain |

| Coordinates | 41°39′23″N 0°53′48″W / 41.656472°N 0.89675°W |

| Current tenants | Cortes of Aragon |

| Official name: Mudéjar remains of the Palace of Aljafería | |

| Type: | Cultural |

| Criteria: | iv |

| Designated: | 2001 (25th session) |

| Part of: | Mudéjar Architecture of Aragon |

| Reference #: | 378-008 |

| Region: | Europe and North America |

| Official name: Palacio de la Aljafería | |

| Type: | Non-movable |

| Criteria: | Monument |

| Designated: | 3 June 1931 |

| Reference #: | RI-51-0001033 |

The Aljafería Palace is an amazing old palace in Zaragoza, Spain. It was built a long, long time ago, in the second half of the 11th century. This palace was once the home of kings and queens. It shows how grand and important the city of Zaragoza was back then.

Today, the Aljafería Palace is still very important. It houses the Cortes of Aragon, which is like the regional parliament for the area of Aragon. This means important decisions for the region are made inside its ancient walls!

The palace is one of the best examples of old Spanish Islamic architecture. It's so special that it's protected as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. Its beautiful designs, like the special arches and detailed carvings, even influenced other famous buildings in Spain.

After Christian kings took over Zaragoza in 1118, the Aljafería became their home too. Over the centuries, it changed a lot. It was a royal residence, then a military fort, and even a prison. It got damaged in wars but was carefully restored in the 20th century to look beautiful again.

Contents

The Troubadour Tower

The oldest part of the Aljafería Palace is called the Troubadour Tower. This tower got its name from a play written in 1836, which later became a famous opera called Il trovatore. The story of the play largely takes place in this very palace!

The Troubadour Tower was built as a strong defensive structure. It has a square base and five levels. It was built around the end of the 9th century. Its main job was to be a watchtower and a strong point for defense. Imagine guards looking out from here for any danger!

The tower was surrounded by a moat, like a ditch filled with water, to make it even harder for enemies to get in. Later, it became part of the larger palace. For a long time, it was even used as a prison, first by the Spanish Inquisition and then in the 18th and 19th centuries. You can still see old drawings made by prisoners on its walls!

The Moorish Palace of Joy

The main part of the palace was built between 1065 and 1081. It was ordered by a powerful king named Abú Ja'far Ahmad al-Muqtadir. He wanted a palace that showed how strong and rich his kingdom was. He even called it "Qasr al-Surur," which means "Palace of Joy"! The main throne room was called "Maylis al-Dahab," or "Golden Hall."

The king himself wrote poems about his palace, saying:

Oh Palace of Joy!, Oh Golden Hall!

Because of you, I reached the maximum of my wishes.

And even though in my kingdom I had nothing else,

for me you are everything I could wish for.

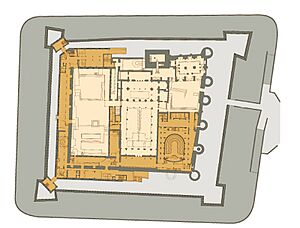

The palace was designed around a central courtyard with pools. The royal rooms and fancy halls were at the north and south ends. The northern part was especially grand, with a second floor and a beautiful entrance to the throne room.

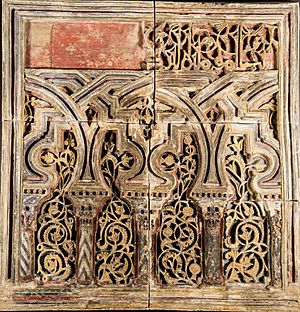

The walls of the Golden Hall were once covered in amazing decorations. They had plants, geometric shapes, and writing. These designs were painted in bright colors like red, blue, and gold. Imagine how dazzling it must have looked!

The Golden Hall

The Golden Hall was the most important room. It had two private bedrooms, one on each side. The western bedroom was used by kings for centuries.

Most of the original wall decorations are gone now, but some pieces are kept in museums. The ceilings and wood carvings in this room were designed to look like the sky. The whole room was meant to represent the universe, showing the king's power over everything.

The entrance to the Golden Hall is very impressive. It has three openings with beautiful marble columns and special arches. These arches are a unique style, found for the first time in the Aljafería, and later copied in other Islamic buildings.

The Palace Mosque

Near the Golden Hall's entrance is a small mosque, or prayer room. It was used by the king and his close friends. It has a special arch at its entrance, inspired by the famous Mosque of Córdoba.

Inside, the mosque has a niche called a mihrab, which points towards Mecca. The walls are decorated with beautiful arches and plant designs. The bottom parts of the walls were covered with marble.

The dome of the mosque is not the original one, but experts believe it would have been very intricate, with interlaced arches forming an octagon, similar to other famous mosques.

Courtyard of Santa Isabel

The Courtyard of Santa Isabel is an open garden area that connected all parts of the Moorish palace. It's named after Princess Elizabeth of Aragon, who was born in the Aljafería in 1282 and later became queen of Portugal.

The courtyard originally had two pools, one to the north and one to the south. The southern pool is still there today. During restorations, the courtyard was brought back to its original beauty with marble floors and gardens.

Palace of Peter IV

After the Christian kings took over, the Aljafería became a royal palace for the Kingdom of Aragon. In the 14th century, King Peter IV of Aragon decided to make some big changes. He added new rooms and built the Chapel of San Martín.

King Peter IV wanted bigger, more comfortable rooms than the older Moorish ones. He added new halls with beautiful wooden ceilings. He also built a special bedroom with an octagonal wooden dome, located right above the mosque.

Chapel of San Martín

The Chapel of San Martín is a church built in a mix of Gothic and Mudéjar styles. It uses parts of the old palace walls. The entrance portal is made of brick and has a unique design with arches and the coat of arms of the King of Aragon.

Inside, the chapel has two main sections with ribbed vaults on the ceiling. These vaults have small flowers with the Aragonese royal coat of arms. The chapel was changed a lot in the 18th century but was later restored to show its original Mudéjar style.

Palace of the Catholic Monarchs

At the end of the 15th century, the Catholic Monarchs (King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella) built a new royal palace on top of the old Moorish one. This new palace was built between 1488 and 1495 by skilled Mudéjar builders, who kept the traditional styles.

To enter this palace, you climb a grand staircase. The staircase has beautiful plaster decorations and a magnificent ceiling. The ceiling is painted with symbols of the Catholic Monarchs, like the yoke and arrows.

The main entrance to the Throne Room is very grand. It has a special arch with the coat of arms of the Catholic Monarchs, showing the symbols of their kingdoms. This entire entrance is made of hardened plaster, a common material in Islamic and Mudéjar art.

Before the Throne Room, there are three smaller rooms called "rooms of the lost steps." These rooms have large windows and were probably used as waiting rooms for people who wanted to meet the king and queen.

The floors in these rooms were originally made of colorful ceramic tiles from a famous pottery in Muel. The ceilings are also amazing, with carved wooden designs, painted and gilded with gold leaf. They feature the symbols of the Catholic Monarchs and hanging pineapples, which represent good luck and long life.

The Throne Room

The Throne Room is truly spectacular. It's 20 meters long and 8 meters wide. Its ceiling is a masterpiece of carved wood, with thick beams and sleepers forming eight-pointed stars and thirty deep square sections. Inside these sections are octagons with flowers and large hanging pine cones. This ceiling design is even reflected in the floor!

Around the room, there's a gallery of arches where guests could watch royal ceremonies. Below the ceiling, a carved frieze tells a story in Latin. It says that King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, with the help of Christ, ordered this work to be built in 1492, after freeing Andalusia from the Moors.

Later History and Restoration

In 1486, the Aljafería became the headquarters for the Spanish Inquisition, a powerful religious court. The Troubadour Tower was used as a prison during this time.

Later, in 1591, there was an uprising in Aragon. King Philip II decided to make the Aljafería an even stronger military fortress to prevent future revolts. New walls, towers, and a wide moat were added around the palace.

The palace continued to be used for military purposes, even as barracks for soldiers. In 1772, King Charles III of Spain ordered a complete transformation into barracks, changing many of the interior spaces. In 1862, four Gothic-style towers were added, and two of them still stand today.

By the mid-1800s, people started to notice that the palace was falling apart. Efforts were made to restore it, but it wasn't until 1947 that a major restoration project began. This project helped bring the Aljafería back to its former glory.

In 1984, the regional parliament of Aragon decided to make the Aljafería Palace its permanent home. The building was adapted for this new use and restored again. Today, the Aljafería Palace stands as a beautiful and important historical monument, serving both as a museum and a place for modern government.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Palacio de la Aljafería para niños

In Spanish: Palacio de la Aljafería para niños

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |